Photograph: Alicia Canter for the Guardian

Chosen by Carson Ellis, award-winning illustrator and sleeve designer for the Decemberists, Weezer and Laura Veirs

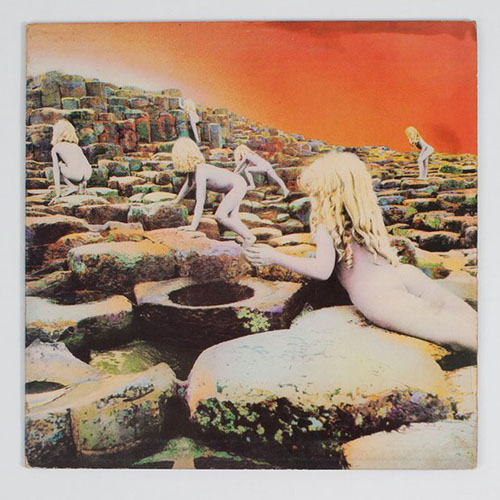

This has been my favourite album cover for as long as I can remember. Hipgnosis did lots of the great 70s sleeves and this is weird, timeless and iconic. I recently did a cover for an album of Zeppelin covers called From the Land of Ice and Snow and redrew the Houses of the Holy image in my own style. So I’ve spent a lot of time with it. It’s a photo collage image of nymph-like, mermaid-like, naked children – actually a brother and sister – climbing Giant’s Causeway, in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Zeppelin combine blues with fantasy and JRR Tolkien, and all that is on the cover. It seems to signify otherworldliness, something primal and social taboos. There’s something vaguely sexualised about the children, but whatever sexuality it’s alluding to is subtle enough that you can shrug it off. On the cover of the Decemberists’ What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World, I drew a stylised, flat depiction of a naked woman, with tiny pink dots for nipples. I was told that big stores wouldn’t stock it. They were the most benign, non-sexual nipples that anyone ever had.

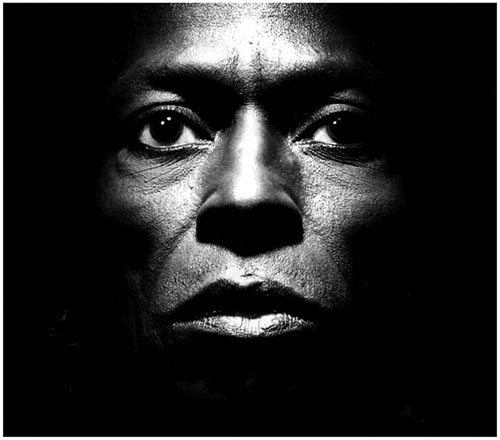

Miles Davis – Tutu (1986)

Chosen by Cey Adams, designer of Def Jam Recordings sleeves from the Beastie Boys, Public Enemy and Jay Z

This is one of Miles Davis’s last recordings, in his avant-garde period – it’s named after Archbishop Desmond Tutu. It’s just a stark photograph by Irving Penn of Miles looking straight on, and the edges are faded black [the cover was designed by Eiko Ishioka]. I was taken by the fact that an artist could have a cover without his name on it, and Miles Davis was obviously so popular that he could do that. Miles always had very powerful features, and the texture and detail in his face shows the journey of his career and how much he put into it. I was drawn to the album by that intense, beautiful stare. I modelled my career on Miles in terms of wanting to push boundaries. For example, Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet was conceptual art, which no one had done in hip-hop before. However, I was so moved by the Tutu cover that when the time came to do LL Cool J’s greatest hits album, All World, I applied the same idea to an Albert Watson photograph of LL. There was type on the front, but it was on a shinkwrap that peeled off. It was my homage to Tutu.

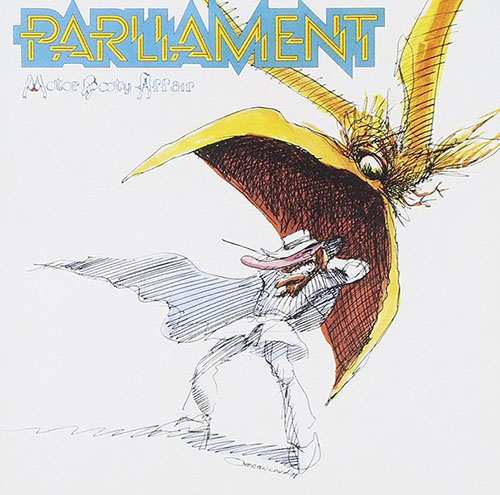

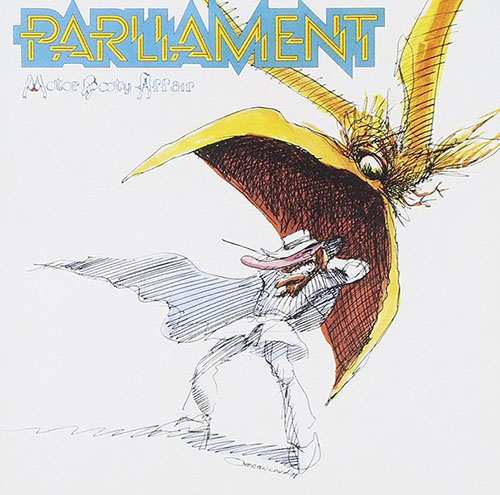

Parliament – Motor Booty Affair (1978)

Chosen by Joe Buckingham, designer of various De La Soul sleeves including De La Soul Is Dead

I’ve always liked album sleeves that double as construction kits. I had a Jefferson Airplane album that you could take apart and build into a fully three-dimensional cigar box. The inner sleeve was an image of marijuana, and that sat in the box, so it looked as if it was filled with grass. In this field, though, this Parliament cover is king and is still my all-time favourite sleeve. It was a gatefold with a pop-up element. If you laid the album flat, this fantasy castle popped up along with various characters you could cut out and stand up in the castle. There were tons of illustrations, and the cover featured a giant bird coming down on the album’s Sir Nose character. There was just so much to look at in Overton Loyd’s artwork. It really piqued my imagination. I think subconsciously the starkness and simplicity of the cover image against a white background seeped into how I designed De La Soul Is Dead.

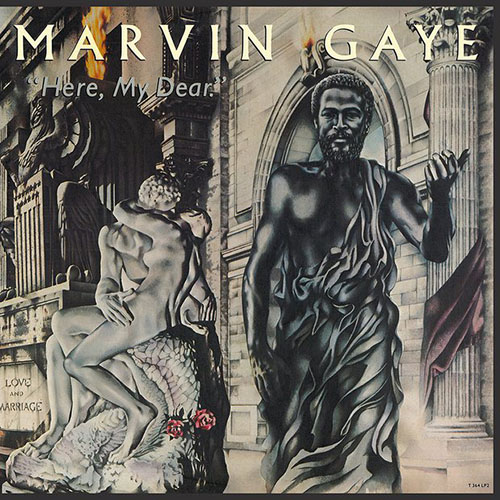

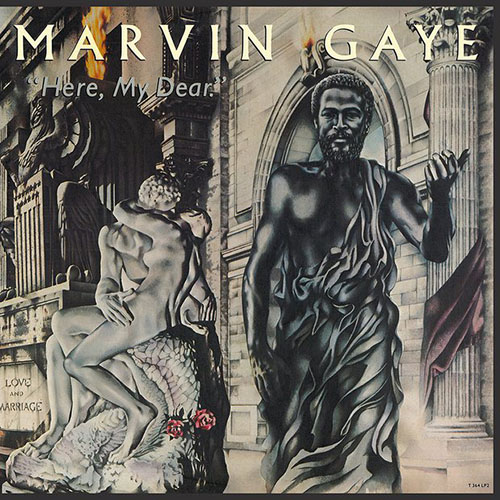

Marvin Gaye – Here, My Dear (1978)

Chosen by Scott Sandler, Grammy-nominated designer of artwork for everyone from Def Jam to Lil Wayne to the Rolling Stones

I love this because of the story behind it and the way the cover works with the music. In the mid-70s, Marvin Gaye had had two enormous albums in What’s Going On and Let’s Get It On, but was going through an acrimonious divorce from Anna Gordy. They agreed a deal whereby she wouldn’t get any money, but would get all the proceeds of his next album, which looked guaranteed to be the biggest record ever. Instead, he sabotaged the deal by making a wilfully uncommercial album, full of songs about their relationship, although it’s now seen as another classic. Gaye gave Michael Bryan, the artist, very specific instructions, so the cover features the singer looking like a Greek god. The artwork includes the words “love and marriage” and “judgment” and it unfolds to a picture of him handing her this itsy-bitsy, teeny-tiny record. That’s dark, but mostly a record just features a photo of the band. This is a total concept, a snapshot of his state of mind and an amazing art piece.

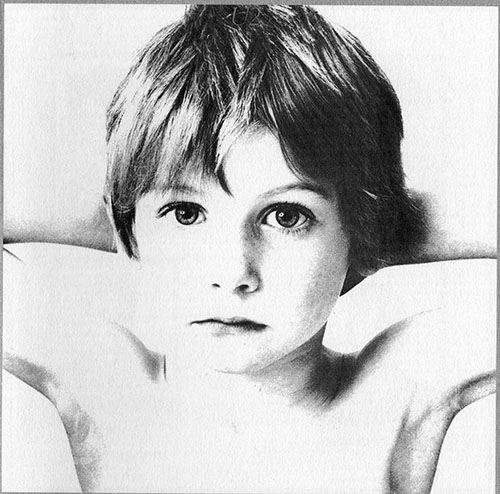

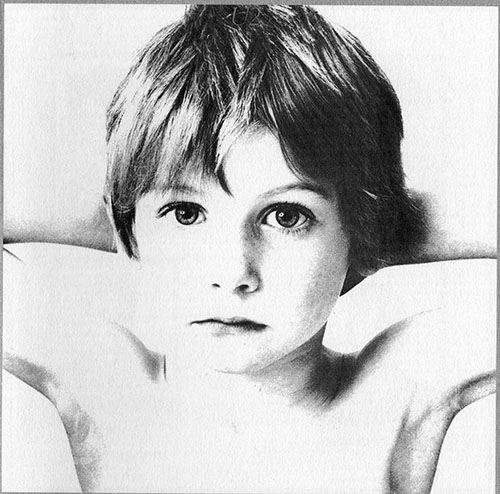

U2 – Boy (1980)

Chosen by Alison Fielding, Beggars Banquet Group creative director, who has designed for the Prodigy, the Specials and the Horrors

When I was about 13, I heard I Will Follow when I was listening to the John Peel show on headphones. I thought it was amazing, and immediately went to this little local shop that sold TVs as well as records, and ordered it. At that point, I had no idea what it would look like. When I got it, I just thought it was so beautiful, I stared at it for hours. I don’t care much for the graphics, but it’s very evocative of a time in my life that shaped my love of music, and there’s something almost Mona Lisa-like about the photograph on the sleeve. Does it capture innocence, or something darker? They used the same boy two albums later for War, by which point he has a split lip. So there’s a narrative developing. When I was about 13 or 14, I had this big blue Adidas bag for school, and I wrote “U2” on it in really big lettering in ballpoint pen, but messily and badly. That was my first attempt at graphics.

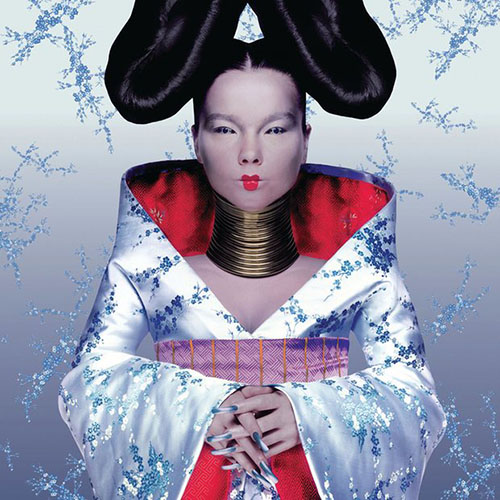

Björk – Homogenic (1997)

Chosen by Rochelle Nembhard, who worked on the acclaimed cover for Petite Noir’s La Vie Est Belle

I like covers that relate directly to the musician, more than abstract images. I like some abstract images, but those covers could be anyone. Homogenic is a piece of art, and the fact that she used Alexander McQueen to design it was amazing. It’s a fusion between African and Asian – the African necklaces and the Asian dress – that stands the test of time. I love all Björk’s covers for that reason – they all show an aspect of her. The visual aspect of music, the album cover, is important, because it is a picture of the music, depicting the sound. It should be so much more than just a one-dimensional image – it has to be the face of the music. That’s what I was trying to do with Petite Noir, working with the artist Lina Viktor. I knew she had the type of imagery that would translate into his music and stand the test of time.

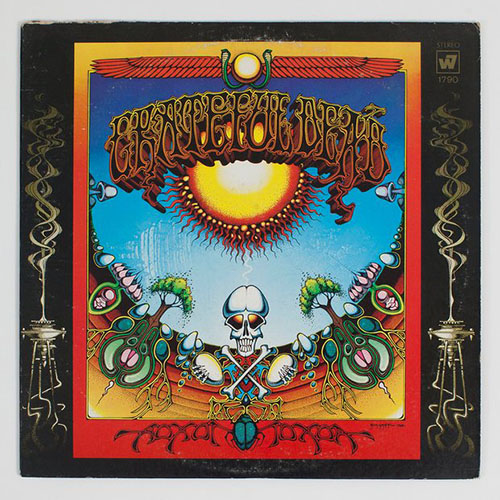

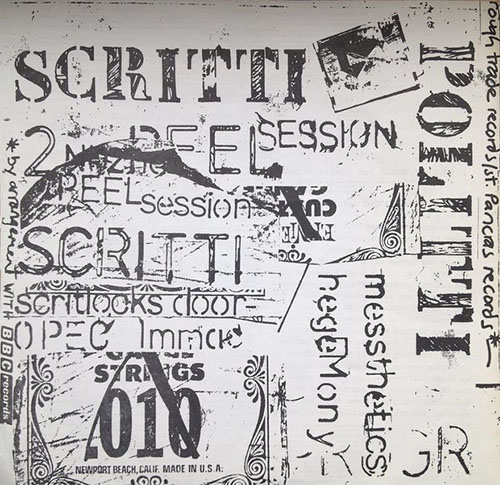

Scritti Politti – Work in Progress EP (1979)

Chosen by Matthew Cooper, designer for Arctic Monkeys, Franz Ferdinand, Hot Chip and many more

I love the DIY aesthetic of the first edition of Elvis Presley’s first album, later homaged by Ray Lowry for the Clash’s London Calling sleeve. The wonky type looks like it has been cut out and stuck on by hand. There’s another musician awkwardly cropped in the photo of Elvis. Nowadays, the record company would ask you to Photoshop him out. The immediacy of the image and graphics make a statement of intent: “Here I am.” Many years and genres after that was released, the same aesthetic inspired me when I came across this EP of Scritti Politti’s second John Peel session in Chick-A-Boom Records in Sutton Market, some years after it came out in 1979 on Rough Trade Records. The sleeve was just a plastic bag with two bits of photocopied paper in it. One of them listed the entire costs of making the record, including £65 for 5,000 plastic covers. The other photocopy was of a bag of crisps, a badge and some sugar. It demystified the entire process and I realised that I could do something similar at the local library. So I took loads of stuff down and started photocopying it.

This piece was amended on 23 September to correct the spelling of Malcolm Garrett’s name.