A woman stands next to the painting at The Arts House in Singapore on Dec. 15. PHOTO: REUTERS

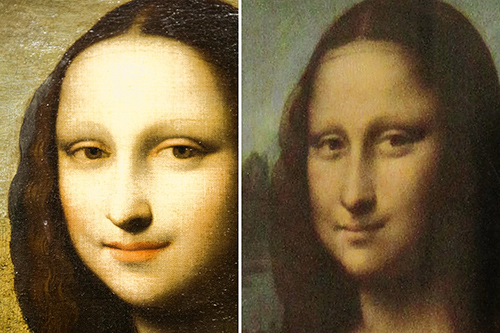

Visitors are led through a detail-packed exhibition, laying out why the foundation believes Leonardo painted the image in the early 1500s, perhaps a decade before the Louvre version. There is an emphasis on cutting-edge scientific probes, from digital analysis of brush strokes to carbon dating and other tests.

A final room nods to critics who say the portrait is a copy of the Louvre painting by someone else, but it portrays this group as a minority.

Leonardo experts remain skeptical. “I do not know of any major Leonardo scholar who has definitely accepted it,” said Martin Kemp, a professor of art history at the University of Oxford.

Much is still unknown about the Louvre painting despite centuries of scholarship.

The Louvre says it is thought to depict Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine cloth merchant, and was “doubtless” painted between 1503 and 1506. The image later entered the collection of King Francis I of France.

Some experts, citing written historical evidence, say the Louvre painting could have been done some 10 years later and believe there is a possibility Leonardo made an earlier portrait.

Florian Knothe, director of the University of Hong Kong’s museum, where the show opens in March, believes it is an opportunity for debate. “The exhibition itself presents both for and against arguments and I believe it is very much about the journey to understanding,” he said.

The painting hanging in Singapore got its first burst of publicity in 1913, when Hugh Blaker, the collector and critic, found it among the artworks at a British manor house. With little known of its prior owners, the work became known as the “Isleworth Mona Lisa,” for the town near London where Mr. Blaker’s art studio was situated.

Henry F. Pulitzer, an American collector, purchased the picture in the 1960s, and wrote a book claiming it was an earlier version of the Louvre painting. His assertion failed to stick.

An international consortium bought the work in 2008. Two years later, the foundation was established to research the painting, and it launched a battery of scientific tests on the canvas.

David Feldman, a leading stamp dealer who is vice president of the foundation, declined to name the owners or to say whether any of the foundation’s members have a stake in the painting. He also declined to detail the last purchase price, or the current insurance value.

He says art experts like Mr. Kemp, who has played a part in attributing other works to Leonardo, fear technological advances will erode their power to assess paintings.

“There is no easy way to get recognition and acceptance from the art world, particularly when connoisseurship in the traditional way is being challenged,” Mr. Feldman said.

Mr. Kemp responds that science is useful to highlight a forgery, by discovering pigments or other materials that weren’t available during an artist’s lifetime, but not to prove authenticity, which requires expertise and visual interpretation. He believes the painting’s style is too heavy-handed to be by Leonardo.

Movers prepare to hang the painting ahead of its exhibition at The Arts House in Singapore, on Dec. 12. PHOTO: REUTERS

Movers prepare to hang the painting ahead of its exhibition at The Arts House in Singapore, on Dec. 12. PHOTO: REUTERS

Although there has been no evidence to prove the picture isn’t by Leonardo, the foundation’s efforts to use science for a positive attribution have faced a series of obstacles.

Carbon dating only has been able to show the canvas of the portrait was produced between 1492 and 1652, a wide date range that doesn’t rule out the possibility that it is a later copy by somebody else.

The foundation also asked Pascal Cotte of Paris-based Lumiere Technology to investigate the painting.

Mr. Cotte’s firm has pioneered a process called multispectral digitization, which reveals original colors of a painting and can pick out preparatory drawings beneath the painted surface.

The foundation, in a 320-page book on the work published in 2012, said Mr. Cotte, who also has done studies on the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, “confirms that the artist was likely the same for both paintings.”

Now, on its website, the foundation makes a more modest claim: Mr. Cotte’s analysis fails to show any reason why the painting “was not by Leonardo.”

Mr. Feldman said Mr. Cotte signed off on the content in the book but later changed his mind. The foundation believes Mr. Kemp, the Oxford scholar, put pressure on Mr. Cotte to do so, he said. Mr. Kemp denied any involvement in the matter.

Mr. Cotte didn’t respond to requests for comment. A statement posted on Lumiere Technology’s website warns of “flashy” and “ambiguous” use of its work to “back up risky conclusions,” although it didn’t give details.

Some other scientists have been more supportive. John F. Asmus, a U.S. physicist at the University of California, San Diego, first examined digitized images of the painting 26 years ago on behalf of the Pulitzer estate.

Although there has been no evidence to prove the picture isn’t by Leonardo, the foundation’s efforts to use science for a positive attribution have faced a series of obstacles.

Carbon dating only has been able to show the canvas of the portrait was produced between 1492 and 1652, a wide date range that doesn’t rule out the possibility that it is a later copy by somebody else.

The foundation also asked Pascal Cotte of Paris-based Lumiere Technology to investigate the painting.

Mr. Cotte’s firm has pioneered a process called multispectral digitization, which reveals original colors of a painting and can pick out preparatory drawings beneath the painted surface.

The foundation, in a 320-page book on the work published in 2012, said Mr. Cotte, who also has done studies on the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, “confirms that the artist was likely the same for both paintings.”

Now, on its website, the foundation makes a more modest claim: Mr. Cotte’s analysis fails to show any reason why the painting “was not by Leonardo.”

Mr. Feldman said Mr. Cotte signed off on the content in the book but later changed his mind. The foundation believes Mr. Kemp, the Oxford scholar, put pressure on Mr. Cotte to do so, he said. Mr. Kemp denied any involvement in the matter.

Mr. Cotte didn’t respond to requests for comment. A statement posted on Lumiere Technology’s website warns of “flashy” and “ambiguous” use of its work to “back up risky conclusions,” although it didn’t give details.

Some other scientists have been more supportive. John F. Asmus, a U.S. physicist at the University of California, San Diego, first examined digitized images of the painting 26 years ago on behalf of the Pulitzer estate.