Four million people (mostly civilian) were killed in the three years of the Korean War, and it is estimated that a million more Koreans were displaced in its aftermath, but here in the United States, the war is frequently referred to as “forgotten.”

Four million people (mostly civilian) were killed in the three years of the Korean War, and it is estimated that a million more Koreans were displaced in its aftermath, but here in the United States, the war is frequently referred to as “forgotten.”

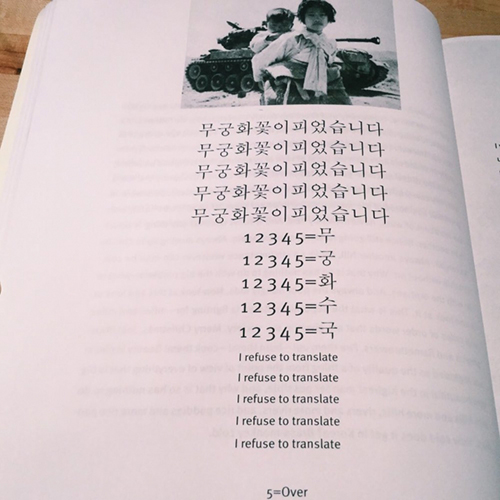

A page from Don Mee Choi’s “Hardly War” (via donmeechoi.com)

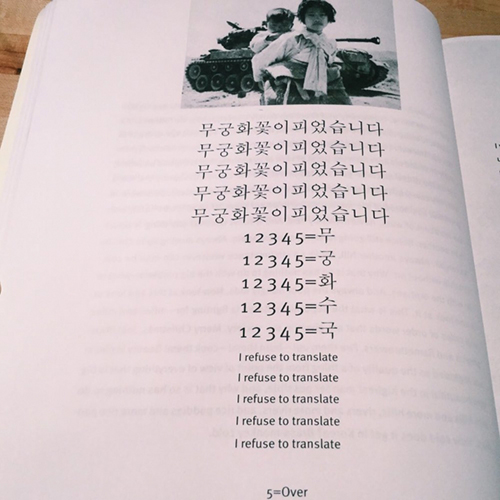

A page from Don Mee Choi’s “Hardly War” (via donmeechoi.com)

Don Mee Choi’s second poetry collection, Hardly War, resists easy categorization. Composed of three sections — “Hardly War,” “Purely Illustrative,” and “Hardly Opera”— it has been characterized as both hybrid and pastiche to acknowledge its fragmentation as well as its wide range of source texts.

The “hardly” of the book’s title is a qualification, and perhaps a bit of a disclaimer. If war is hardly war, what attention need history pay? For Choi, poet and translator, it depends upon where you stand. Four million people (mostly civilian) were killed in the three years of the Korean War, and it is estimated that a million more Koreans were displaced in its aftermath, but here in the United States, the war is frequently referred to as “forgotten.”

But Choi’s parents survived the war and “did not forget,” she explains in an essay on The Volta Blog. “Their memory formed the lining of the womb in which I was conceived.” When Choi was a child, her parents fled the military dictatorship in South Korea to live in Hong Kong, but her father, a photojournalist, spent most of his time in war zones in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. “I saw more of my father’s photographs than of my father,” she explains in the opening pages of Hardly War.

Her father’s photographs and writings are woven throughout the text. Choi’s other sources include accounts of the conflict by historian Bruce Cumings, news reports, and lines from films such as the 1962 cold war thriller The Manchurian Candidate and another Hollywood depiction, Pork Chop Hill. The range and diversity of her sources provide texture and richness, but Choi’s decision not to attribute specific sentences or phrases to their sources creates uneasy collisions between and among references. An early fragment reads:

It was hardly war, the hardliest of wars. Hardly, hardly. It occurred to me that this particular war was hardly war because of kids, more kids, those poor kids. The kids were hungry until we GIs fed them. We dusted them with DDT. Hardly done. Rehabilitation of Korea, that is. It needs chemical fertilizer from the States, power to build things like a country. In the end it was the hardliest of wars made up of bubble gum, which GIs had to show those kids how to chew.

The reference to “we GIs” suggests a first-person account, yet “…kids, more kids, those poor kids” seems to be the voice of an outside observer, and the “poor kids” could just as easily refer to the GIs themselves — most American troops sent to Korea were young and tragically inexperienced — as it could to the war orphans, often depicted as roaming the ruined streets. These lines claim no authority beyond that of the poet herself, juxtaposing voices and sources to invite re-interpretation.

Choi explains in a note that Hardly War took its inspiration from a 2007 musical composition by Heiner Goebbels, which is in turn inspired by Gertrude Stein’s text, Wars I Have Seen. Stein’s influence haunts this text, and is visible in the passage quoted above. The repetition of the words “hardly,” “hardliest,” and “kids” call certainty into question. What kind of war involves children? Can it be called a war? Should it be? The “kids” here are poor, they are hungry, they are chewing bubble gum. What is childhood in the onslaught of war?

Choi deconstructs and recomposes her materials, consistently resisting conventional narrative logic. Writing is an act of decolonization, she asserts, which requires “disobeying history, severing its ties to power.”

Her juxtapositions at times can be powerful and poignant — her father’s photograph of a North Vietnamese refugee girl is placed opposite an image of the “daisy girl” from Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidential campaign ad against Barry Goldwater. The girls might be around the same age — one, carrying her brother as they flee their home; the other in a field of wildflowers, picking petals from a daisy.

At other times, meaning is more intentionally elusive. Beneath a photograph of a young Korean girl carrying her brother on her back past a stalled M-26 tank, Choi repeats lines of Korean text, then, beneath the Hangul, writes, “I refuse to translate.” We are compelled to confront what we do not or cannot know. Or, Choi might suggest, perhaps it is that we routinely ignore what hardly seems to concern us.

Hardly War animates what typically remains untold: “the faintly remembered, the faintly imagined, the faintly discarded.” Choi explains the logic her language employs,

I’m trying to imagine race=nation, its language, its wars. I am trying to fold race into geopolitics and geopolitics into poetry. Hence, geopolitical poetics. It involves disobeying history, severing its ties to power. It strings together the faintly remembered, the faintly imagined, the faintly discarded, which is to say race=nation gets to speak on its own faint history in its own faint language.

In the end, the effect of these faintly imagined voices speaking on their own faint history is disorienting, unsettling. Hardly War requires an attentiveness that destabilizes narrative. “What are world memories,” one voice in a poem asks. “It turns out that they are war memories.” The meaning of wars cannot be reported by the powerful, by the military and government leaders who orchestrate them. As Choi reminds us, the real victims of war are the civilians, too often only faintly remembered.

Don Mee Choi’s Hardly War (2016) is published by Wave Books and is available from Amazon and other online booksellers.