The Rise Of Fake And Forged Works Of Egyptian Modern Art

The discovery of fake and forged works has been something that has plagued the art market for centuries. There have been a number of famous cases, including the fake Frans Hals that Sotheby’s recently sold for ten million dollars, only to have to revoke the sale after the work was revealed as a forgery. On the contrary, there is very little written on the rise of forgery in non-Western artistic tradition. I have recently become incredibly fascinated by the rise of fake and forged works in Egyptian modernist art, which was sparked by the incredible story of my friend Ahmed Khedr’s family.

I am very lucky to have access to such a personal account of forgery and the Khedrs very graciously provided me with a firsthand explanation of their case. The Khedrs were the first individuals to ever bring to court the issue of fake and forged works in Egypt. The family’s story, as well as the general rise of forged works in Egypt’s art market, bring up a multitude of the issues surrounding copies and fakes in the better known cases. In my interviews with both Ahmed and his mother, May Zeid, we examined the complex psychology behind the forgery and the many motivations behind forging and faking famous works of art. Their story is also an example of a forger who took advantage of the ideal situation and time to create these forged works, in this case a rise in market value and a desire to celebrate Egyptian culture and art. Lastly, Egypt is a country in which laws protecting collectors against frauds barely exist. This, along with a general lack of knowledge of Egyptian modern painting, makes Egypt a unique example in terms of contemplating innovative solutions to thwart the production of fake and forged works.

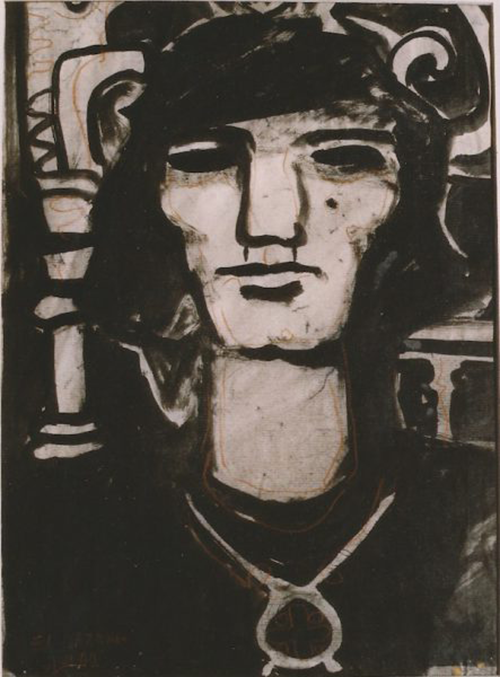

The main artist that Ayoub and Hassan forged was a painter named Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar

Fake El Gazzar Painting

The forgeries came to light with the opening of an exhibition of Samir Rafi, an important artist that Zeid and Khedr had been interested in. Ayoub and Hassan previously tried to sell to them works by Rafi but Zeid and Khedr had never been interested in those specific works, which is fortunate for Zeid and Khedr as they were undoubtedly fake. Zeid and Khedr brought Hassan with them to the exhibition as an adviser and decided to purchase a couple works from the show. The dealer came to Zeid and Khedr’s house to finalize the payment and see their collection. At the time, Darwish did not make any comments on their collection, which Zeid and Khedr thought to be very odd. Shortly after the payments were completed, Darwish sent Zeid and Khedr a book on Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar and Said El Farsi’s collection, which were both not available for purchase. When Zeid and Khedr opened the catalogues, they were shocked to find the same paintings hanging on their walls, with slight variations. In El-Gazzar’s catalogue, they saw parts of separate paintings all combined in one of the works they owned. At the sight of this, Zeid and Khedr invited a different dealer over, who notified them that three-quarters of their collection was likely to be inauthentic. Zeid set up a meeting with El-Gazzar’s wife and brought the El-Gazzar works Ayoub had sold her. El-Gazzar’s wife knew immediately that the works were not only fake, but the products of Ayoub and Hassan. She told Zeid that Ayoub and Hassan had been forging El- Gazzar’s work for a long time and she had tried to get them arrested on several occasions but was never successful. El-Gazzar’s wife had seen many of the same works circulate throughout the years and had spoken to many of the victims of Ayoub’s con. Unfortunately, prior to Zeid and Khedr, these victims would make deals with Ayoub, who would return their money in exchange for the fake paintings, which she’d quickly resell to others.

Because of this, Ayoub’s con business was kept relatively under wraps and she was never faced with legal repercussions. As Zeid said herself, “It was a structured plan where they would keep selling fake paintings, make a large profit and if they were ever caught, they would silently return all the money, regain back the forgeries and move on to the next victim”.2 Zeid and Khedr were the first to ever challenge this. When Zeid and Khedr first approached Ayoub and Hassan about the forgeries, they offered to not press legal charges if their money was returned and the forged works were destroyed in front of them. They made it clear that they would not accept any deal that did not include the destruction of the fakes. Not only did Ayoub and Hassan decline this offer, they began to spread rumors that Zeid and Khedr were actually the ones who were forging works.

At this offense, Zeid and Khedr decided to take the forged works to the police. No member of the police department had any knowledge of the art market and was in fact shocked at the amount of money that these works sold for. Because many of the transactions were without invoices and receipts, Zeid and Khedr’s only evidence were the paintings themselves and the witnesses they were able to collect to testify. Fortunately, they managed to bring together an impressive number of individuals that were willing to testify on their behalf in court. On top of this, they embarked on collecting documentation and reports signed by experts in the art world that would attest to the works being fake. Their witnesses included members of the Conservation Department at the Egyptian Museum of Modern art, other collectors who had been victim to Ayoub’s con, the artists’ relatives, and one living artist that Ayoub had forged named Hassan Soliman. Soliman recalled Ayoub and Hassan meeting at his studio several decades back. He also testified that at this same time, Hassan, who was hired to clean his studio, must have started collecting unfinished works that Soliman would toss aside. Hassan finished these

works and later on, with Ayoub’s direction, sold them as original works. On the defense, Hassan claimed that the works were indeed real and that he had only sold Zeid and Khedr three out of the eighteen works on trial. Ayoub denied involvement altogether and maintained the argument that Zeid and Khedr had forged the works themselves. The premise of her argument was that Zeid’s aunt was a painter and had painted Zeid a fake Monet, which Zeid had hanging on her wall. Although Zeid’s aunt signed her own name and was quite obviously not attempting to trick or con anyone, Ayoub argued that Zeid’s aunt had forged the eighteen works.

Fake Mahmoud Said Watercolour

After the testimonies, the court called upon a committee of experts to examine the paintings, who gave a unanimous decision that the works were fake. The court declared Ayoub guilty as the main offender and Hassan as her accomplice. Because the court has no specific laws against art forgery, Ayoub and Hassan were charged more generally with embezzlement and fraud. She was sentenced to a year in prison and Hassan was sentenced to three. Ayoub and Hassan appealed the court’s decision and a new panel of judges were appointed to look over the case. After the surprising new decision that Ayoub and Hassan were innocent, it came out that Ayoub had bribed one of the judges to produce a verdict in her favor. Zeid and Khedr rightfully appealed and the case was taken to the Supreme Court. Ayoub was charged with a year in prison in May of 2006 and passed away in December 2006 from heart failure, before her sentenced started. Although she did not live to serve her sentence, the last couple months of Ayoub’s life were filled with shame and her reputation, both professional and personal, was completely destroyed. Hassan also passed away before his sentence of three years began. Zeid and Khedr, although not fully satisfied with the country’s lack of legal protection against art forgery, raised significant public awareness on the issue of forgery and were able to stop Ayoub from selling another fake work ever again. They continued to collect Egyptian art and have since built one of the most impressive collections in the country. Furthermore, they are very proud to have taken the moral route, even though the legal system, among other issues, seemed to be against them.

Forged works by Ayoub and Hassan circulated the art market in Egypt for thirty years. Ayoub took advantage of the country’s lack of knowledge on Egyptian modernist painters as well as the the absence of laws to protect against the purchase of forged works. She struck at the ideal time, as many forgers do, when demand for Egyptian modernist works was high. Ayoub, who was also an aspiring painter herself, shared with Hassan a sense of satisfaction each time they got away with their con. She would frequently tell Zeid that she longed to be “a famous artist one day, even if it ends up being the death of me”.3 The fact that people paid high sums of money and believed their creations to be real boosted their egos and justified their own belief in their artistic skills. Each time they would sell a work, they were able to internally prove themselves as equals to some of the biggest Egyptian artists in the 20th century. Ayoub enjoyed in particular that she was able to con and make fools of some of the most intelligent and cultured people in Egypt. It seems evident that for Ayoub her success was not only in terms of monetary value, but served a psychological purpose, as is the case with many other studied forgers.

Words By Gracie Brahimy © Artlyst 2017