The House of World Cultures’ exhibition tells the story of the Congress for Cultural Freedom’s use of an aesthetic of freedom, and contextualizes the lasting legacy of modernism within the geopolitical power struggles of the Cold War.

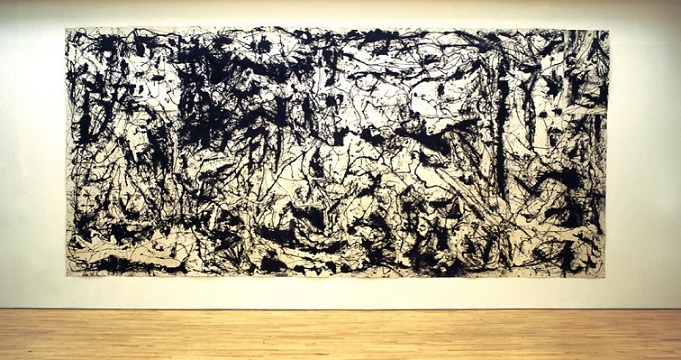

Art & Language, “Picasso’s Guernica in the Style of Jackson Pollock” (1980), glue, cardboard, canvas, oil paint, paper (courtesy of S.M.A.K., Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent)

BERLIN — Jackson Pollock — the art world’s Marlboro man, an icon of freedom in postwar America — may owe part of his legacy precisely to that image, and its potency for America’s Cold-War cultural battle. A new exhibition in Berlin’s House of World Cultures (HKW), Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War, looks at the little-known history of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an association of intellectuals and cultural producers that first met in West Berlin in 1950, and dispersed in 1967 when its funding ties to the CIA were exposed. The history of the CCF is no secret — you can read all about it on the CIA’s own website. But the HKW exhibition tells the parallel story of the CCF’s aesthetic of freedom, and contextualizes the lasting legacy of modernism within the geopolitical power struggles of the Cold War.

After World War II, the CIA’s strategy in Europe was to strengthen intellectual elites who supported socialist policies but not Communism, who they termed the non-communist left. Doing so without having those actions traced back to the US, however, was challenging. The CCF was one solution: its director Michael Josselson proposed that strengthening the non-communist left should be done through cultural organizations rather than straight-out political ones. The CCF would gather European influencers under the guise of promoting “cultural freedom” —and indeed most intellectuals and artists involved in the congress were not aware of its CIA bankrolling. The CCF was founded in Berlin and went on to assert influence over writers, artists, and intellectuals in Cold War frontiers throughout Africa, Asia, and West Asia. Its operations assumed that modernist expression in literature, art, and music forged a path for spreading capitalism, democracy, and liberalism in the American model.

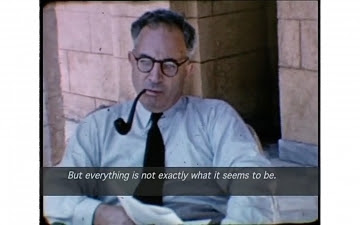

Still from Lene Berg’s “Man in the Background” (2006) (screenshot by the author)

Could anything communicate white, male freedom more than Pollock’s drip paintings? Or embody abstract thought more than Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings? Secret agents could never have invented better antidotes to Socialist Realism — all they had to do was push these all-American exports as hard as they could. One of the CCF’s activities was to organize traveling exhibitions of 20th century art from American collections (primarily MoMA’s) across Europe. These exhibitions posited Abstract Expressionism as a natural development, à la Alfred Barr, to the European, prewar avant-garde. They asserted both a new canon and a new brand of all-American imagery. The HKW doesn’t miss its chance to merrily topple male-modernist myths, and adds a new twist: these celebrated artists were cogs in the capitalist expansion, unbeknownst to them, frontmen for the CIA’s global mission to plant the aesthetics of freedom.

Modernism was by no means the only American aesthetic of the time, though it was the most potent as an international symbol of freedom. The exhibition collects some enlightening alternatives. Norman Lewis’ “Untitled (Police Beating)” from 1943 is a blurred depiction of a white policeman beating a black man in which abstract strokes connote movement, oppression, and a white onlooker’s glee. Lewis did not separate abstraction from social subjects, and his brushstrokes are not expressions of internal storms but of real violence. On the other hand there are Norman Rockwell’s scenes of prosperity in white America: realistically rendered images depicting abstract values such as “Freedom of Speech” or “Freedom from Want” (1943). Neither of these perspectives would fit into the FCC’s vision of cultural freedom: the first was too social and marginal, the second too small-town, too kitsch. Instead, the aesthetic of American freedom would be delivered in bold colors and broad gestures, through powerful, inscrutable individuals and formal innovation. Both this aesthetic and its chosen champions continue to inform current images of freedom. Parapolitics traces the history of freedom as an ideology with its own aesthetics: an ideology that prioritizes individual rights over communities, and can rationalize such American freedoms as the right to bear arms or limitless free speech.

Norman Lewis “Untitled (Police Beating)” (1943) watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper, 20” x 13 7/8”, signed and dated, (private collection; © Estate of Norman W. Lewis; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY)

Visitors to the HKW exhibition are not subjected to the brainwashing impact of a real Pollock or Reinhardt. Instead we get painted black-and-white copies, photos of people looking at paintings, and contemporary work mixed in amongst a crowded system of see-through space barriers. The curators have apparently decided to be self-conscious and transparent — to contrast the authority and opacity of the CCF. But this strategy becomes tedious as endless amounts of reading materials are displayed in vitrines in a kind of bibliographical display, a testament to years of international research. It is as though the curators assume that by gazing at hundreds of documents, unable to read them all, you should be imbued with an understanding of how complex these politics are. These display choices, unfortunately, deliver their own argument: that evidence, discourse, and research can yield academic truth. The exhibition asserts that multiplicity in itself makes a subject more genuine, and identifying hegemonies at once dismantles them. This argument of truth in multiplicity repeats in the contemporary works as well: a clever video by Lene Berg “The Man in the Background” (2006) paints a layered portrait of Michael Josselson, the colorful Eastern-European Jew who came to America before the war and became the director of the CCF. Berg’s interview with Josselson’s widow, Diana, is interspersed with archival footage of the couple abroad. Berg loops the footage with seven different narrations, each adding a dimension to Josselson’s character: agent, victim, independent thinker, political organizer, imposter, idealist, scapegoat, and opportunist. All narrations are valid, but the truth — the exhibition seems to tell us – lies in somehow holding all of these perspectives in mind at once.

Still from Lene Berg’s “Man in the Background” (2006) (screenshot by the author)

The questions raised in the exhibition are important and pertinent. Artists and viewers of art are still trained to value the individuality, abstract thought, imagination, and power of artists’ works. These modernist ideals have retained their relevance many years after modernism itself. Perhaps knowing this history can unravel some of these myths, and allow other images of freedom become valid in the public eye.

Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War, continues at the House of World Cultures (John Foster Dulles Allee 10, Berlin) through January 8.