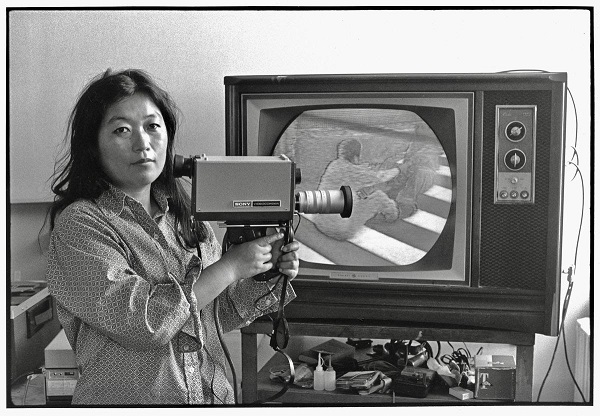

When Sony introduced its Portapak camera in 1967, it put the first truly portable video camera into the hands of the public. Artists were quick to start experimenting with this new tool, and an entirely new art form, called video art, soon emerged. A narrative codifying its development would later take shape. “Fathers” of the medium were designated: Peter Campus, Bill Viola, and, perhaps most prominently, Nam June Paik. But video art had mothers, too—and central among them is Shigeko Kubota.

As it happens, the mother-father framework applies particularly well to Kubota and Paik. They fell in love while they were both key members of the Fluxus group in New York, beginning in the early 1960s. In 1977, they married. Like the tangled cords running from the monitors in their work, the personal and professional were intertwined in the life they created together.

They fueled each other’s creativity, but Kubota’s substantial legacy became overshadowed by her husband’s equally formidable work. “We are very different, like water and oil,” she said in a 2009 interview. “Even when I did my own stuff, people said, ‘She imitates Nam June.’ I found it infuriating. So I headed further in the direction of [Marcel] Duchamp. When Nam June went populist, I went for high art.”

Kubota was born in Niigata, Japan, a prefecture whose fertile rice production slated it for nuclear destruction during World War II. But nature intervened, as she once explained: “I was in second grade when the bomb went off….[The Americans] were supposed to drop the bomb over my town, Niigata….but it was cloudy, not sunny, so they went to Nagasaki instead. That changed my life.”

Kubota came of age in the post-war period. She began her university studies in sculpture in Tokyo in the late 1950s, when the city was the seat of a burgeoning avant-garde in Japanese art. In 1964, she was ready to stake her place in this scene with her first solo show at Naiqua Gallery, which she filled with a mountain of love letters and crushed paper covered over with a white sheet. Visitors had to scale this rather challenging form in order to discover an array of sculptures of welded metal pipe that Kubota had placed at the top. The critics ignored her coming-out.