Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s personal experience of migration would inform the prodigious output of her art and writing in the 1970s and early ’80s.

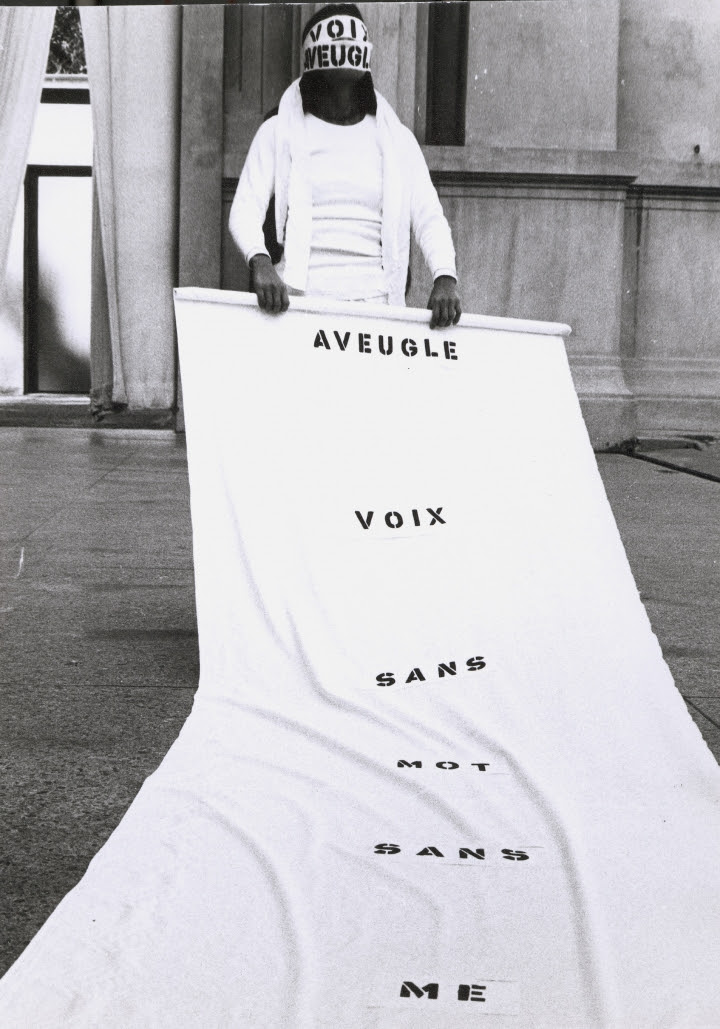

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, “Aveugle Voix” (1975), performance, 63 Bluxome Street, San Francisco (BAMPFA, gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation, photo by Trip Callaghan)

BERKELEY, Calif. — At age 12, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha emigrated from her birthplace of Korea in 1963, two years after a military coup took over the south and a decade after the Korean War resulted in an armistice that divided the country in half. Cha’s family was, if not accustomed to living in diaspora, at least familiar with displacement and adapting to a new language and culture. Her parents grew up in Manchuria during the Japanese occupation of Korea and returned to their home country only during World War II. Korea remained an unstable and elusive homeland as Cha and her family eventually immigrated to the US and settled in the San Francisco Bay Area.

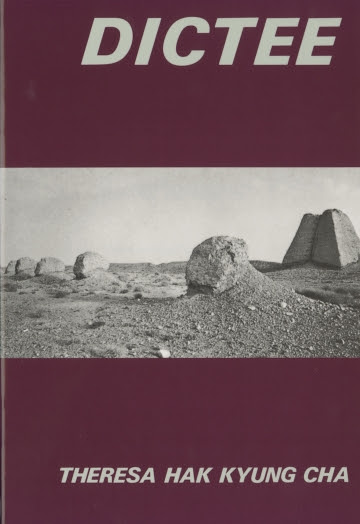

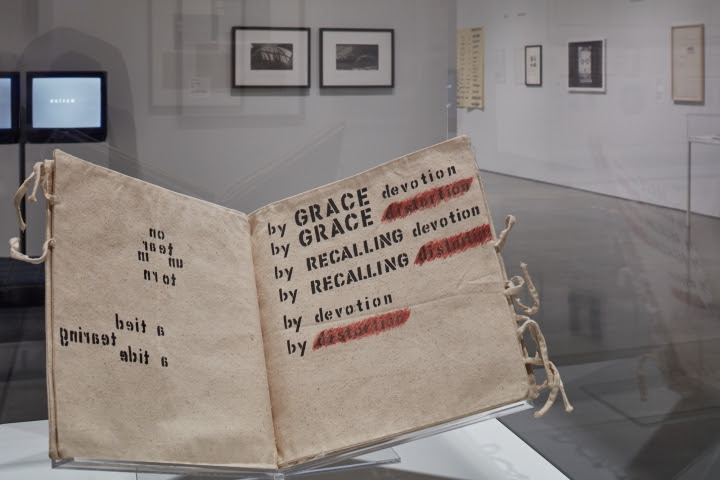

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee (1982), artist’s book, published by Tanam Press (BAMPFA, gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation)

Cha’s family history and personal experience of migration would inform the prodigious output of live performance, video art, film, poetry, works on paper, and criticism she produced as a young artist and writer. In 1969, she embarked on almost a decade of study at UC Berkeley, where she earned four degrees in literature and art, joined a community of artists, and emerged as a promising artist and scholar. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha: Avant Dictee at UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) brings together over 50 works of art from the museum’s collection, grouped by the 10 thematic chapters of Cha’s most famous published work, Dictee.

“Berkeley in the 1960s and ’70s was a time of great change, and this was the case at UC Berkeley in particular,” BAMPFA assistant curator Stephanie Cannizzo told Hyperallergic in an email. “With the advent of new departments like Ethnic Studies and Women’s Studies, the university was broadening its mission to encompass a wider range of perspectives, making it fertile ground for Cha to expand her own horizons as a young, intellectually curious creative voice.”

Cha’s work is highly conceptual yet emotionally resonant. Dictee, published in 1982, is emblematic of the artist’s output in that it addresses themes of time, language, and memory that recur in much of the artist’s work while incorporating multiple forms of media, language, and historical material.

Installation view of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha: Avant Dictee at BAMPFA (photo by JKA Photography, all images courtesy of BAMPFA unless otherwise noted)

Nine chapters, structured around the muses of Greek mythology, result in a form that is novel, prose poem, biography, and photo book all at once. Stories of real and mythic women who lived in extremes against dangerous odds and patriarchal violence are interspersed with letters, photos, diagrams, and calligraphy. Martyrs (Joan of Arc and Yu Guan Soon), mystics (Saint Thérèse of Lisieux), estranged families (Demeter and Persephone), and Cha’s own mother Hyung Soon Huo appear as fellow travelers across time. The anxiety of losing one’s voice and history as well as the violence of acquiring a new language in place of another lie beneath the surface of the book’s text and images.

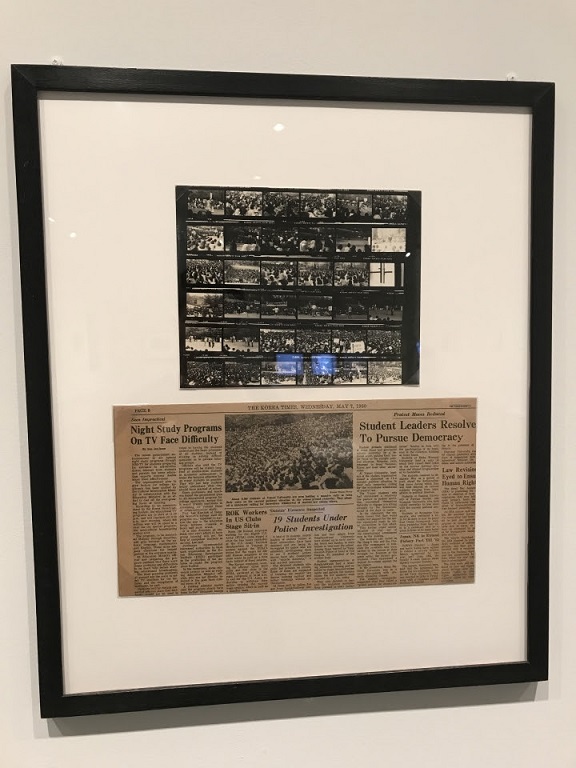

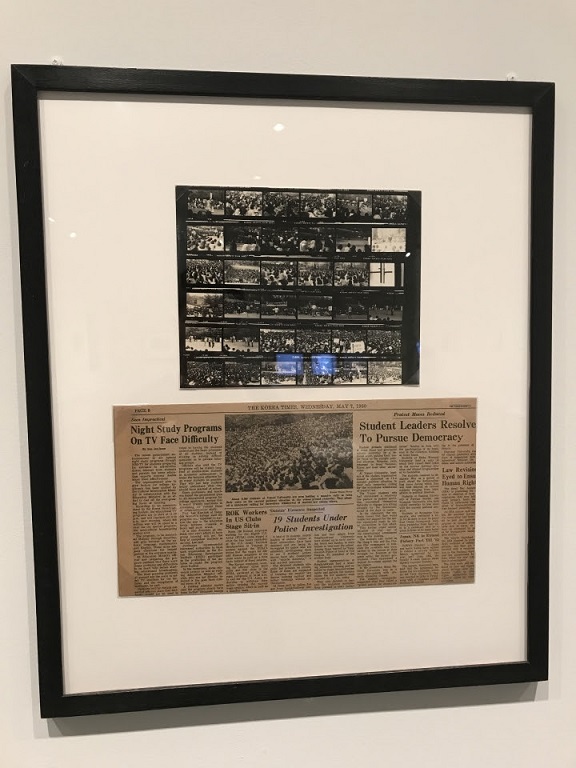

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, “Untitled (Korea)” (1980), black-and-white contact sheet and newspaper clipping (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Avant Dictee outlines the trajectory of artworks leading up to and beyond the publication of Dictee. In 1980, Cha returned to Korea with her brother James to begin work on a film project titled “White Dust from Mongolia.” Photographs from the trip depict a Korea that was likely very different from the country Cha had left 17 years prior, but also very much the same. They depict mass political demonstrations against yet another authoritarian regime that would cause suffering, instability, and exile. Tragically, Cha would not live to complete the film and witness the democratization of South Korea in the following decade, as she was raped and murdered three years later in New York City at the age of 31.

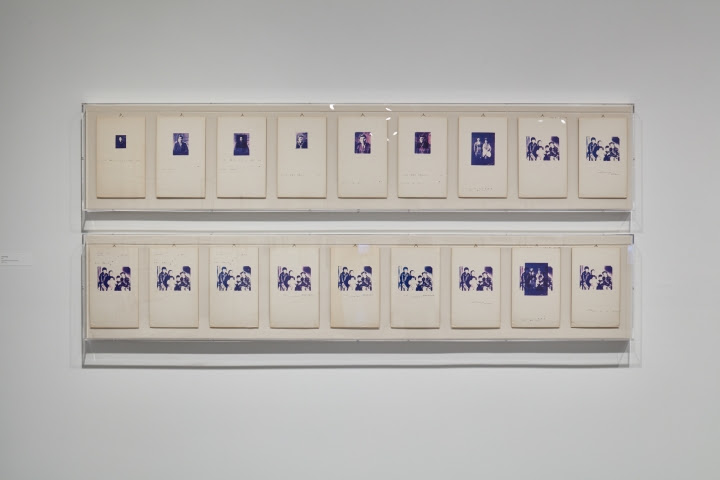

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, “Chronology” (1977), color photocopies mounted on board, 18 sheets (BAMPFA, gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation, photo by JKA Photography)

In over roughly a decade, Theresa Cha seemed to live her life with the same intensity of the women depicted in Dictee, sharing their seriousness of purpose and intent and tragically their early deaths. Her diverse and substantial body of work is now held at BAMPFA, the institution at which she once worked and had formative experiences as a budding artist and scholar. More than three decades later, her ideas about language and stories about women also remain more relevant and powerful as ever, as speech, migration, and women’s stories continue to be contentious in today’s political and cultural climate.

Installation view of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha: Avant Dictee at BAMPFA (photo by JKA Photography)