Disclaimer: Several of the images featured in this article are sexual and explicit in nature.

Carolee Schneemann

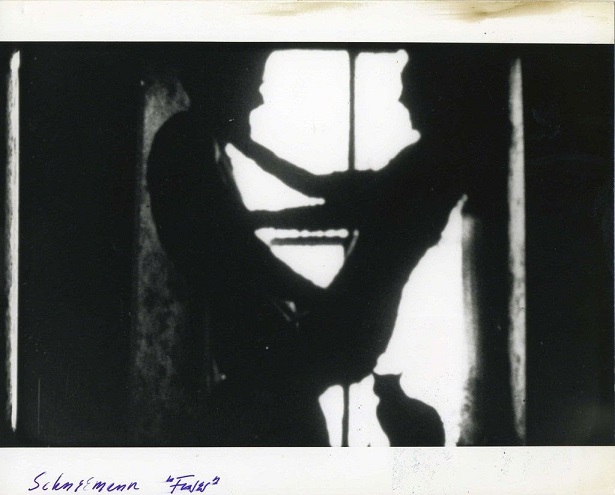

Fuses, 1965

P.P.O.W

In 1964, Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart delivered America’s most famous definition of pornography: “I know it when I see it.” At the time, he was defending Louis Malle’s The Lovers, a 1958 French film starring the smoky-voiced Jeanne Moreau as an adulterous housewife. The black-and-white romance is tame by today’s standards; the case itself would be ludicrous in our era of Pornhub.

Yet academics worldwide continue to debate the distinction between art and pornography. In America, where both have been integral to conceptions of free speech, an adult film star and our president are currently vying for moral authority on a very public platform. Like the Stormy Daniels affair and all other good sex scandals, explicit films—whether they should be classified as art or pornography—often raise questions about gender equality, power, and even capitalist structures.

After all, it’s harder to overlook a sex tape than a painting. Curator Jenny Schlenzka has put a highbrow example of the former on view in an exhibition at Performance Space New York (it’s also online, though decidedly NSFW). The 1974 film, titled Blue Tape, is a collaboration between writer, artist, and punk goddess Kathy Acker and conceptual artist Alan Sondheim. The brainy pair discuss Freudian dynamics (Acker refers to Sondheim as her father and says she uses him as an analyst to access otherwise unreachable memories) before launching into sex.

Acker complains about Sondheim’s technique, and the nebbish Sondheim doesn’t stop talking throughout his entire blowjob. Schlenzka has described the film as “almost unwatchable.” It’s certainly difficult to listen to Sondheim philosophize at an increasingly higher, more urgent pitch. As the actors excavate the ways in which power shifts during sex, the ability to receive pleasure becomes increasingly at odds with maintaining control.

Scenes from Western Culture, Lovers (Álfrún Magnúsdóttir and Atli Bollason)

Ragnar Kjartansson

Scenes from Western Culture, Lovers (Álfrún Magnúsdóttir and Atli Bollason), 2015

Luhring Augustine

When asked whether she thinks the work is pornographic, Schlenzka gives a complex answer. “It’s not pornographic because it’s not meant to be arousing,” she tells Artsy. “But there’s a pornographic element in how it’s explicit. Also what you’re left with is a sense of estrangement, not a sense of connectedness.” Pornography, in her mind, is “never about warmth or emotional proximity.”

Schlenzka articulates a few of the many frameworks that scholars have used to distinguish art from pornography. In his 2012 paper “Who Says Pornography Can’t Be Art?” University of Kent senior lecturer Hans Maes outlines what he believes are the four major theories, and then argues against them.

First: Pornography is sexually explicit, while art is not. “Art reveals in concealing, whereas pornography conceals in revealing,” he simplifies. Acker’s film, obviously, doesn’t conceal much.

Second: Pornography is exploitative, vulgar, immoral, and ultimately harmful, where art is not. One need only look at the story of Auguste Rodin’s muse, Camille Claudel, or one of Pablo Picasso’s many discarded lovers to see how painters and sculptors—not just self-proclaimed pornographers—have destroyed, or at least damaged, women’s lives throughout their processes.

Third: Pornography is one-dimensional, sans artistic merit, as “the pornographer’s sole intent is sexual arousal.” Pornography is an industry, its products “mass-produced commodities.” This neglects, of course, the commercial nature of the art world and the fact that some pornography has a more complex agenda.

Kathy Acker

Robert Mapplethorpe

Kathy Acker, 1983

"Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium" at Los Angeles County ...

Still from a film by Erika Lust. Courtesy of Erika Lust.

Still from a film by Erika Lust. Courtesy of Erika Lust.

The last argument is about “prescribed response,” says Maes. “Indeed, the fact that we speak of consuming pornography and of appreciating art indicates that there is a fundamental difference in how we are meant to engage with both kinds of representation.” The two approaches, he argues, are not mutually exclusive.

Over five decades ago, Carolee Schneemann was already producing this kind of erotic feminist film. The artist, whose first comprehensive retrospective just closed at MoMA PS1, created Fuses in the mid-1960s. In the video, she and her partner have sex as their cat watches. In quick, shadowy, color-saturated shots, genitalia and copulating bodies flicker across the screen, interspersed with images of a window, the trees outside, and the cat’s silhouette. The artist controls her own representation and pleasure, resisting objectification. Schneemann fought against some of her feminist contemporaries’ belief that all pornography must carry a misogynist message.

Notably, some of the male artists best known for working at the intersection of art and pornography take alternate approaches. The Destricted film series, released in 2006, features work by Larry Clark, Gaspar Noé, and Matthew Barney. Isolation, alienation, and devalued sexuality feature prominently in their films, which respectively focus on men auditioning to be pornography actors; people masturbating alone; and the costumed artist penetrating a machine—specifically, a deforestation Caterpillar truck. And for a more romantic investigation of the line between art and pornography, see Ragnar Kjartansson’s 2015 video Scenes from Western Culture, Lovers (Álfrún Magnúsdóttir and Atli Bollason).

Still from Elin Magnusson’s Skin (2009). Courtesy of the artist.

Still from Elin Magnusson’s Skin (2009). Courtesy of the artist.

On the other side of the spectrum is Swedish artist Elin Magnusson, whom Maes cites in his article. In her 2009 film Skin, which has been on view in venues from New York’s New Museum to Sweden’s Arbetets Museum, two figures in nude bodysuits start making out, cutting away parts of their costumes as they grow more aroused. Magnusson describes Skin as “art meets porn,” suggesting, as Maes does, that the categories need not be mutually exclusive. The artist combines larger ideas about intimacy, self-revelation, and the body into a work that, ultimately, still ends with explicit sex. Magnusson’s work aligns with that of another Swede working well outside of a fine art context, Erika Lust. According to her website, the director considers herself a leader in the “ethical adult cinema” movement. Lust compares the ethos behind her work to that of organic produce in the age of fast food, advocating fair labor practices, a focus on women’s pleasure, diversity, and high aesthetic quality.

Notably, the work of artists like Schneemann and Magnusson subverts one of Schlenzka’s ideas about pornography: that it requires estranged partners. As the pair of artists challenged that conception, they also created aesthetically elevated footage. In contrast, the artist Andrea Fraser once made a prosaic sex tape about a meaningless encounter to address other targets: money and the New York art world. In her film Untitled (2003), she sleeps with a collector who paid around $20,000 for the experience (and a DVD recording of the encounter). Fraser examines the relationship between artist and collector, art and prostitution. That’s not to mention the relationship between artist and critic: Notably, Guy Trebay’s New York Times Magazine piece from 2004 further objectified her, highlighting Fraser’s physical attractiveness and likening her to a “hooker with the heart of gold.”

Fraser’s approach, with an overhead camera capturing the tryst, links her back to Acker. “It’s one of the first truth-and-sex tapes,” says Schlenzka about Blue Tape, suggesting that it’s also a forerunner to Paris Hilton’s explicit, leaked footage. Celebrity sex tapes, she says, have “a big impact on the public mind and public consciousness,” whether or not they are intended as art. Schlenzka goes a step further, connecting the country’s prurient interest in these projects to the voyeurism inherent in today’s social media culture. One wonders, if Acker were alive today (she passed away in 1997), just what her Instagram account might look like.

For his part, Maes has written that we should encourage artists “to make intense, powerful, and profound works of pornographic art and rescue this much-maligned genre from the clutches of the seedy porn-barons.” Elsewhere, in a 2017 paper titled “The Aesthetics and Ethics of Sexiness,” he calls for “radical egalitarian pornography” to alter viewers’ perceptions of sexiness as they relate to such factors as gender, race, age, class, and disability. The distinction between art and pornography becomes less interesting than work that pushes at the boundaries of the two.

Alina Cohen