To be great in the arts, must one be appalling at home?

The works of Pablo Picasso “demanded human sacrifices,” his granddaughter Marina wrote in a memoir. “No one in my family managed to escape [from his] stranglehold.…He needed blood to sign each of his paintings.”

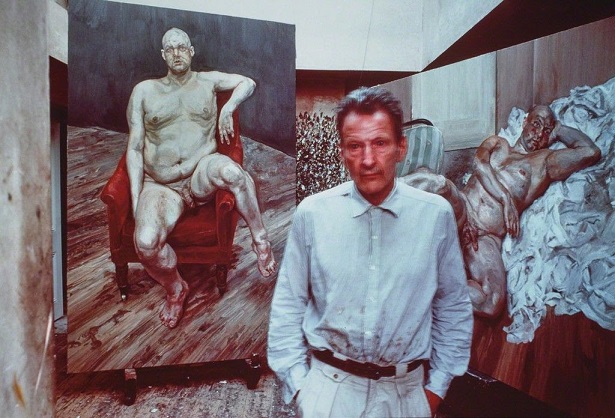

Or consider Lucian Freud, known for portraits of melancholy and isolation, who was himself the cause of much melancholy and isolation beyond the canvases, siring at least 14 children and troubling himself little with their lives. One daughter, Lucy, told a British newspaper of her attempts to connect with the great man: “I invited him to my wedding because I thought, he’s a father, even though he wasn’t a Dad.” Freud didn’t even respond.

It’s not just painters—ask those who’ve lived among filmmakers, musicians, and authors. The greats are not always destructive egotists, but a striking number have been. Which raises an uneasy question: Could behaving horrendously make the art better?