We spoke to Stephanie Manasseh, Founder and Director of the Accessible Art Fair, about a quiet but seismic shift happening in today’s art market.

Stephanie Manasseh, Director and Founder of the Accessible Art Fair. Image courtesy of ACAF.

In May 2014, a lone gunman opened fire in the Jewish Museum of Belgium on Rue de Minimes, Brussels. An important repository of Judaica and cultural artifacts both historic and contemporary, the building is a significant symbol of the continuation of shared culture and mutual experience in modern Europe. The attack claimed four lives, and the museum stayed closed for four months.

In 2016, the Accessible Art Fair (ACAF) opened up the space to an international group of emerging artists, and nearly five-thousand patrons. “I really try to link the two, the architecture and the art”, says founder Stephanie Manasseh, “we presented 75 living artists in that space which had suffered so much damage”. She gives heavy emphasis to the word ‘living’: the ACAF is all about presence.

Founded in Brussels in 2007, the Accessible Art Fair has spent the last eleven years providing a crucial platform for emerging artists. At these open and inclusive events, always held in prestigious architectural surroundings, artists present their own work to buyers from every echelon of the art world, from first-time browsers to established collectors. Traditional models of gallery-representation give way to an inclusive, dialogic space in which art as a profession and as a pursuit can thrive. The artist is present.

Punters and artists at the ACAF in 2017. Image courtesy of ACAF.

The success of the ACAF (which Stephanie pronounces “ay-kaff”) is one important barometer of a trend which has been ongoing for at least a decade: that of artists valuing, representing and selling their own work directly to collectors without the mediation of galleries and other institutions. Whilst not yet ‘the norm’, this model is seemingly the stuff of the very-near-future. “It’s happening. This is the way things are going”, says Stephanie.

The benefits to the artists are obvious. Being able to take the valuation process into their own hands, self-mediating the initial reception of their works, and of course bypassing the 50% cut of the sale-price that galleries take are all attractive options, especially for early-career artists.

But what are the benefits, and what are the potential risks, to buyers? The model is, of course, more transparent and more open, but should collectors be worried about the removal of large institutions from the process?

For artists lucky enough to secure gallery representation, the costs and logistics of storage and exhibition are often reliably covered. Further, the content of the work is safeguarded in legal terms pertaining to copyright and insurance. Collectors know that the work they’re buying has been treated with the kind of security and care which contributes to its value. In less tangible terms, the public reception and the cultural value of gallery pieces are fostered through a well-established network. For tentative buyers who want to ensure a canonical ‘prestige’ in the works they purchase, perhaps gallery-affiliated artists still carry with them a particular clout and a kind of future-proofing of critical reception.

“I really don’t think there are any additional risks to the buyer”, says Stephanie. Her belief, and her experience, is that a direct transaction is mutually beneficial. For one thing, the artist is able to offer a price that hasn’t been raised to offset some of the 50% gallery commission, and so the potential value to an investor is high. Further, if the buyer is given first-hand insight into the processes of a work’s inception and creation by talking to the artist themselves, this can add value to the experience, Stephanie believes. “This has been said so many times, but it’s just so true: you have to buy what you love”, she says. The ACAF works on the principle that open communication between artist and buyer is more likely to bring about that falling-in-love moment, and open up that experience for a broader range of people than ever before: “If you’re a first-time buyer it’s not really about investment. Just buy what moves you.”

The BOZAR in Brussels, designed by Belgian architect Victor Horta, the venue for the 2017 and 2018 fair. Image couresy of ACAF.

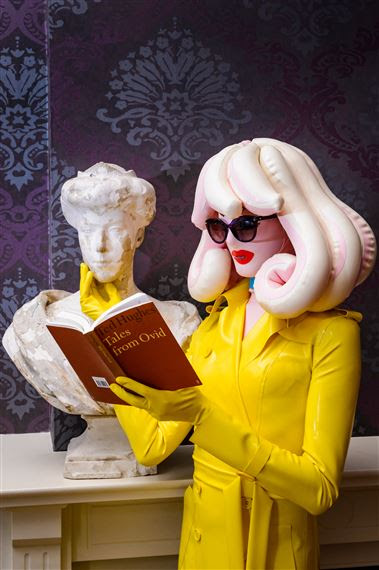

Another benefit of artists controlling their own marketplace is that it opens up new and exciting forms of art to collectors. The MoMA’s acquisition of Tino Sehgal’s Kiss (2009) eight years ago, and Paddle8’s auction-sale of Ragnar Kjartansson’s performance piece Sad, sad, sad (2013), are two of the exceptions proving a general rule: the marketplace has a difficult relationship with non-tangible forms of art. Artist-led fairs like ACAF are beginning to change that. One of the most exciting artists to present their work last year was London-based performer and designer, Pandemonia, who uses synthetic signs and symbols to create a lived-subjectivity. “She’s a true artist”, says Stephanie, but in the same breath admits she would have “no idea where to start when it comes to representing a performance artist!”

Instead, she suggests buyers or other people interested in the art-market meet artists like Pandemonia themselves and gain knowledge and insight into valuable contemporary artworks whose very nature resists the traditional modes of representation and monetization.

London-based artist and designer, Pandemonia, who presented their work at last year's fair. Image courtesy of ACAF.

The works available at the ACAF are vetted strictly by a jury, ensuring that the best emerging art is offered for sale. It’s worth also noting that the fair takes place in culturally significant locations, presenting the works in open dialogue with the architecture surrounding it, allowing them to occupy a field of mutually communicated credibility. This year, the ACAF returns to the Palais de Beaux-Arts, or ‘BOZAR’, a stunning art-nouveau building in central Brussels, designed by Victor Horta. “It’s one of the most important art spaces in Belgium and Horta is one of the most well-known architects. It’s just really exciting to welcome people in such an important institution. It gives credibility to the whole thing”, says Stephanie. “I think that it really fits the vision of the architect to make art visible to people”.

In the Jewish Museum in 2016, Stephanie and the ACAF highlighted how the living organism of the art-world can help reclaim communal spaces. Similarly, their ongoing mission helps to reclaim the marketplace for those whose work occupies it and open it up for more and more people to engage with. “We’ve seen a quiet revolution”, says Stephanie. It’s happening. This is the way things are going.