정준모

Peter Zumthor’s smoked glass box contains Bourgeois’s sculpture.

A collaboration between the late artist Louise Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) and architect Peter Zumthor (1943 – ), the Steilneset Memorial (2011) commemorates the 91 people (77 women and girls, and 14 men) who were executed during the 17th-century trials, mostly by burning at the stake. More people in the Finnmark region — then home to only around 3,000 people or 0.8 percent of Norway’s population — were executed for witchcraft than anywhere else in Norway, which accounted for 19 percent of all Norwegian trials and 31 percent of all death sentences. The memorial sits on the very site, off the shore of the freezing Barents Sea, where it is believed the condemned were burned.

Louise Bourgeois “The Damned, The Possessed and the Beloved” (2011)

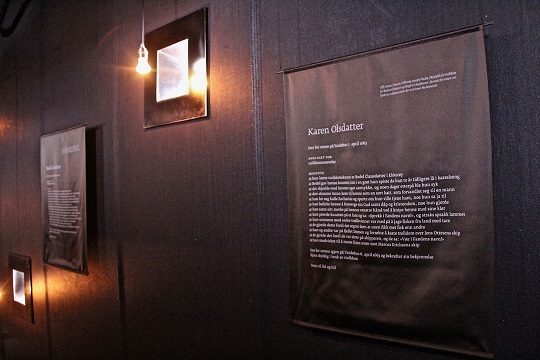

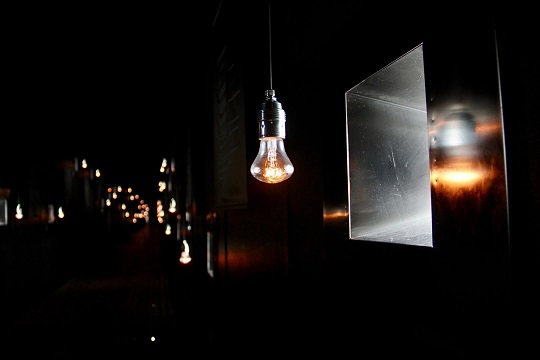

The memorial is made up of three components, art, architecture, and history. Zumthor’s 400-foot-long oak-floored pavilion — swathed in sailcloth and lit by light bulbs hanging in each of the 91 steel-framed windows — leads toward a steel and smoked-glass box. Inside, sits Bourgeois’s sculpture, “The Damned, The Possessed and The Beloved.” It is unsparingly literal, a burning steel chair encircled above by large oval mirrors.

Zumthor’s pavilion is lined with small windows lit by bare lightbulbs.

I return to the memorial several times during my four-day stay on Vardø. Each time I walk through it, the small windows lining the hallway feel critical to my ability to breathe, they let a little light into the encompassing darkness. Each time I reach the hall’s midway point, it feels as though it might be too overwhelming to continue, to take this all in, the hatred of the accused, the spitefulness of the accusers, the denouncing of one another. The narrative would often erupt with linked cases: One person is denounced by an acquaintance, who is then themselves denounced and brought before the court. And so on. The stories conjure up an atmosphere of suffocating paranoia. Toward the end of the hall, one banner tells of a woman named as Sámi Elli who cries as she was “manhandled and sent by boat to Vardø” and was chided for it by her co-accused, Magdelene Jacobsdatter, who says: “You think this is bad, but we will suffer far worse.”

Vardø isn’t an easy place to get to, I flew two hours from Oslo to Kirkenes and took a four-hour ferry journey to the island. It is difficult to imagine that the mania that engulfed central Europe could reach someplace so remote. But that, it seems, is the point. There is a long tradition of placing hell in the far north — pre-Christian Norse legends say that “the road to Hell lies downwards and northwards” — and of portraying the people of the north as sorcerers. The notion was a favorite motif of writers throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, from the “lapland sorcerers” of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (1594) to the “lapland witches” of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). Sámi men, in particular, writes Willumsen, are “reputed throughout Europe to be well-versed in the art of magic,” known for their ritual use of the rune drum. Fearing them as a powerful and visible part of the Sámi religion, Christian missionaries destroyed many drums. The case against Anders Poulsen, a 100-year-old Sámi man, is built on his using a drum. When brought before the court, he “confesses” to having learned to use the drum “in order to help people when they were in trouble, and to do good deeds.” Poulsen, the final victim of the Finnmark trials, was murdered while in custody in February 1692 with an axe. The context helps account for why, when it comes to the male victims of the Finnmark witchcraft trials, Sámi men outnumber Norwegian men, making up 68 percent of the victims. (the opposite is true of the women).

A view of the Arctic island of Vardø.

Although completed seven years ago, the Steilneset Memorial is important now. While powerful men claim themselves victims of witch hunts, twisting the meaning of the term, and displaying deliberate ignorance of social hierarchies, we see the motif of the witch resonating in contemporary art. First shown at the 57th Venice Biennale and opening at Edinburgh’s Talbot Rice Gallery this month, Jesse Jones’ Tremble Tremble (2017) positions the figure of a witch as a feminist archetype. In a work she calls a “bewitching of the judicial system,” her witch disrupts history, reading lines from the testimonies of three of the last women to be executed as witches in England — Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susannah Edwards — and from the Malleus Maleficarum, a medieval text written in 1487, and used to identify and prosecute witches. She reads the lines backwards. Stories of the condemned, the long silenced, are finally heard.

Jones’s title comes from the 1970s Italian wages for housework slogan Tremate, tremate, le streghe son tornate! (“Tremble, tremble, the witches have returned!”) and emerges out of a rising social movement in Ireland that played a historic role this year in the repeal of the Eighth Amendment (which grants equal rights to women and fetuses). Tremble, it says. The ground is shifting. We are on the verge of a radical change. This, not the aggrieved cry of a powerful man, is a repositioning of the witch we will hear of more.

The Steilneset Memorial is located at Andreas Lies Gate, 9950 Vardø, Norway and is open 24 hours a day.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari