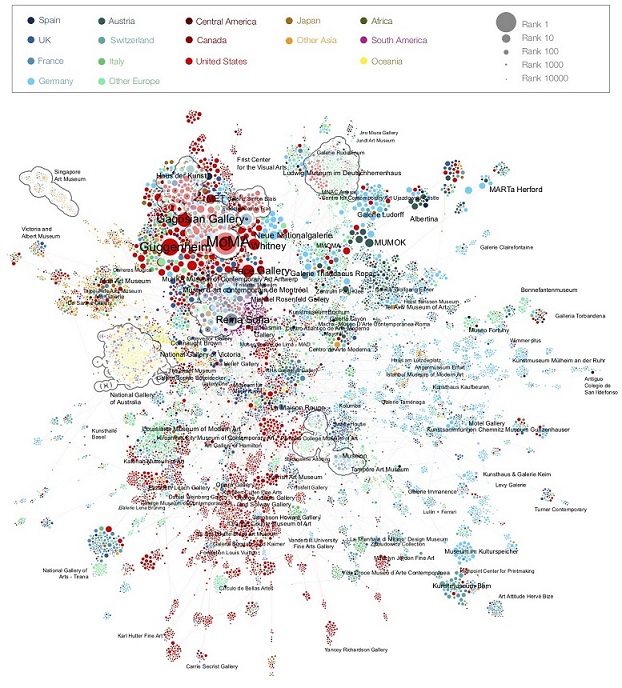

A data-generated map of art institutions, ranked by “centrality,” showing how their relative influence shapes artists’ careers. Click to enlarge.

COURTESY MAGNUS RESCH

“Don’t start a gallery. It’s tough.” This is written in big letters on the back of my book Management of Art Galleries. The struggles of galleries and artists have been much in discussion over the past years. In a long article two years ago, ARTnews reported on numerous gallery closures in New York and how the gap between mega galleries and the rest widened. After having observed the space for many years—as academic, gallerist, and internet entrepreneur—I realized: There are two art worlds. There is the tiny fraction of galleries and artists at the top that make all the money. And there is the other world, much larger in size but with artists and gallerists who can barely afford rent. For years, I have been trying to understand the factors that lead some to success and others to failure. A study that I recently completed and which was published in Science contributes to this discussion.

Three years ago I launched my app Magnus. Using crowdsourcing, my team of 45 employees was able to compile a database recording the careers of roughly half a million artists. It contains hundreds of thousands of exhibitions at more than 20,000 galleries and museums. It also includes information about almost 10 million artworks offered and sold at auctions and galleries. Eventually, we had so much material that I reached out to Laszlo Barabasi, Sam Fraiberger, Roberta Sinatra, and Christoph Riedl—all leading network science researchers at Harvard and Northeastern, to work with me on the data.

The outcome of our effort is a map that unveils the effect on artists’ careers of a powerful network of art institutions; it captures how art moves around the world and how institutions are linked by the artists they exhibit. We ranked each institution based on its “centrality” a mathematical concept drawn from Network Science and one that is at the core of the Google search ranking algorithm. We discovered that, among a large number of fairly ineffectual institutions, one hub stood out as truly transformative. The most central in this hub were two museums, the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim, followed closely by two commercial galleries, Gagosian, and Pace. Next came three more museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Whitney. An exhibition at one of these is a guaranteed ascent to fame and headline prices. It is the definition of artistic validation.

It was devastating to unfold this map. Ninety-nine percent of all institutions scored low and there was only one route to success. If an artist was not part of the central hub, he or she was stuck in an island network, where only limited success is achievable and probability is low to ever cross the bridge to the mainland. No more than 240 artists who began exhibiting in an island were able to enter the central hub. That’s 240 of 500,000.

Chances to make it as a gallery are equally low. Most galleries show “island” artists, so findings from my previous research for The Management of Art Galleries were confirmed: galleries are in bad shape—30 percent run at a loss, with a further 55 percent making less than $200,000 revenue. Only a few galleries make the big bucks—they are the ones with high centrality (Gagosian and Pace, from the central hub, as well as Hauser & Wirth, Zwirner, and others among the so-called mega galleries).

There is no better place to see this network in action than the floor plan of Art Basel in Basel, Switzerland. The galleries in the central hub are located on the ground floor, when you enter to the left, with Gagosian gallery the nexus of all the influential players. The further away you are, the more remote your island. The booths for young and emerging galleries are squeezed into corners on the second floor, out of sight of the ground-floor elite. They are here only to entertain the big guys—like clowns, with no chance to ever make it to the main act. In Art Basel’s Miami edition it’s no different. Nova, the section for upcoming galleries, is tugged into the corner, isolated from the central hub, where Champagne and oysters are served.

Can this undemocratic and impenetrable structure be broken? I think not. Success in the art world is a feedback loop, and those on the inside do not gain from disrupting the status quo. If a collector pays a million dollars for a piece of art, it’s in everyone’s interest—collector, artist, gallery—for the work to at least hold its value. Nor are the museums excluded from this cabal. The same collectors who bought the piece sit on the museum’s board and will most likely donate the work to the museum, which then attracts visitors, media attention, sponsorship money, and donors at all levels. And fairs? They revised their pricing. A younger gallery now has to pay slightly less for its booth than the mega gallery. Positioning five Nova galleries around Gagosian would certainly help more.

To further think of ideas that help level the playing field we need to think outside of the box. Why not implement a lottery system that offers underrepresented artists access to high-prestige venues? And why not conduct blind selection procedures when the museum board buys a new artist? This is already successfully implemented in classical music. It would force the inclusion of neglected artists and certainly strengthen the representation of female or black artists.

While this current structure might be bad for artists and galleries, it’s good for investors. Like fortune-tellers, our data now predict the fate of almost any artist from whether they start out at the periphery of the network or at its heart. If we use their first five exhibits as input, the patterns of where they would show next are so predictive that we can map out their trajectory decades into the future. The common belief that the community will sooner or later “discover” an artist is simply wrong. Moneyball for the art world has arrived.

Why did the predictions work so well? Precisely because performance in art can’t be measured objectively. Nobody can assign value to an artwork simply by looking at it. All types of art, whether poetry, sculptures, novels, dances, or paintings, are essentially priceless. What gives art its value is a powerful network of curators, art historians, gallery owners, dealers, agents, auction houses and collectors. This inner circle doesn’t only determine the works you and your children will see on museum walls—it defines what will break records in the salesrooms and which galleries make it. So value in art is in the network. Any work in any gallery, from the Mona Lisa to a Basquiat, is garage sale material without it.

Magnus Resch is a professor for art economics, bestselling book author and founder of the Magnus app, the Shazam for Art. His paper “Quantifying Reputation and Success in Art” was published in November 2018 by Science.

Copyright 2018, Art Media ARTNEWS, llc. 110 Greene Street, 2nd Fl., New York, N.Y. 10012. All rights reserved.