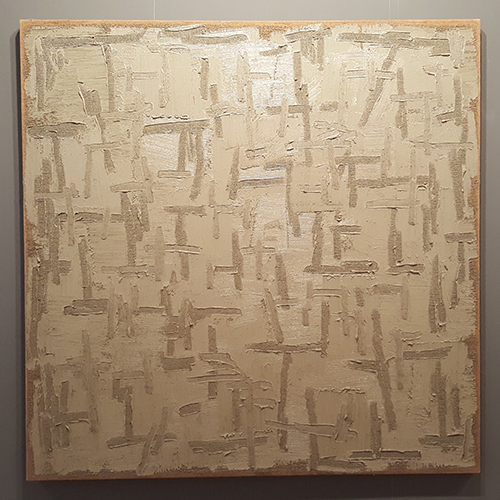

A work by Ha Chong-hyun presented by Kukje Gallery and Tina Kim Gallery (click to enlarge)

Following the trend of the already-canonical, the Korean painting movement Dansaekhwa was difficult to miss on the first floor of the fair this year. The Korean gallery Kukje and its New York partner Tina Kim brought the most exquisite selection of Korean modernists yet: Ha Chong-hyun, Chung Sang-hwa, and Lee Ufan, but the standout was a small black painting from 2000 by Park Seo-bo, with folded Korean Hanji paper that makes it look sculptural like the paintings of Manzoni (of which there were also many in the fair, including one stunning “Achrome” from the 1950s at Dominique Levy). The Korean monochrome painters reappeared elsewhere, too — Pace Gallery was showing a far less impressive Lee Ufan.

Amid tons upon tons of repetitive work, there were some unexpected jewels to be found. These included the paintings and drawings of Russian conceptualist Pavel Pepperstein at Kewenig and an amazing new concrete and wood sculpture by Colombian artist Doris Salcedo in the White Cube booth. It’s hard to concentrate on more art after seeing an 11-meter-long Gerhard Richter in the Marian Goodman booth, but the week was long and the show must go on. The strange photographs of Hans Bellmer, a tiny Etel Adnan, and small pieces by Kazimir Malevich and Ilya Kabakov were among the fair’s other pleasant surprises.

Closeup of Gerhard Richter, “930-7 Strip” (2015), presented by Marian Goodman Gallery (click to enlarge)

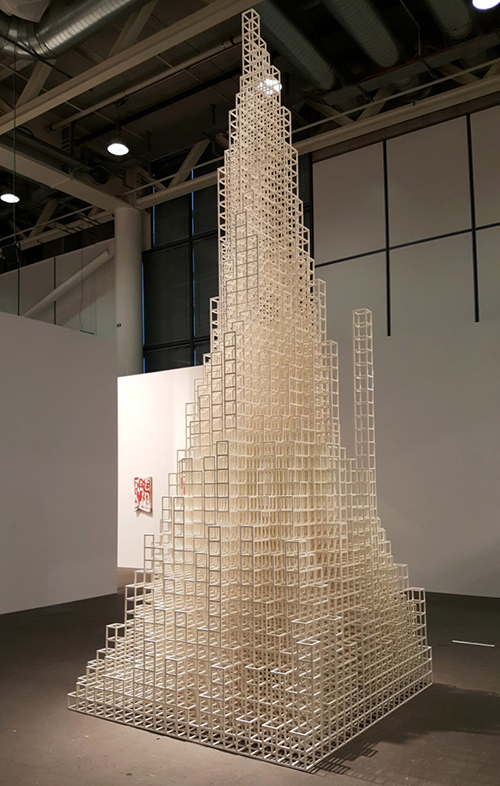

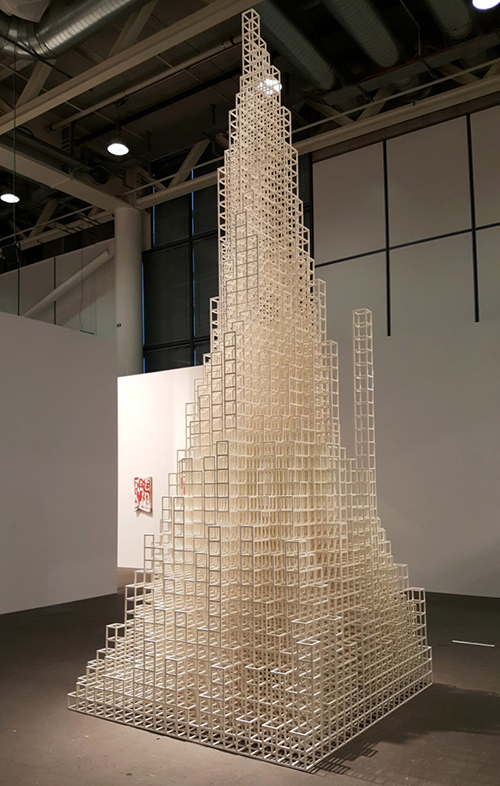

Were there any rising contemporary stars at Art Basel? Not really. It was like a show of dying stars — dying stars and dead stars. The fair featured very little digital art, almost no video, and a few presentations of photography that aren’t really worth mentioning (unless you’re really into Wolfgang Tillmans). Even at Unlimited, the fair’s section devoted to oversized works that do not fit in a traditional booth, the aesthetics of the past took over. Sol LeWitt’s “Irregular Tower” is from 1999 but it could have been made in the 1980s; James Turrell’s “Wedgework,” a really mesmerizing installation playing with light and space, is from 2016 but fits right in with his space constructions of the 1960s. A couple of performances programmed for the space failed to capture much attention; William Kentridge’s film was a bit tiring. Kader Attia’s shelf installation about the newspaper industry was more compelling than his broken vitrines in the same section last year — but still more gigantic than interesting.

Nevertheless, there was some rather outstanding work at Unlimited on the other end of the artistic spectrum, toward experimental practices. The panoptic audiovisual installation of security cameras by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Krzystof Wodiczko, shown by Carroll / Fletcher, addressed the predatory nature of security technologies and was frankly mesmerizing. AA Bronson’s idea of the queered zen garden seemed simple but was actually very politically charged, inverting the symbolic value of everyday objects. The Hong Kong artist Samson Young brought a strange project that many people interacted with at the hall, even if they didn’t realize it. The Long Range Acoustic Device is a sound canon capable of broadcasting sound to a precise target across a distance of one kilometer. During the fair, distressed birdcalls could be heard throughout the exhibition hall, with Young stationed in an inaccessible booth, maneuvering the device during the fair’s opening hours. Young’s discrete work was an anomaly; bigger is always better according to a trend in contemporary art, in which average work supposedly becomes great when it is supersized.

Inside Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Krzysztof Wodiczko’s installation, presented by Carroll / Fletcher

Returning to the main hall for the last hours of the fair, one could get a closer look at what was inaccessible during the opening. For me, this was a fascinating painted installation by Ettore Spalletti being shown by the Italian gallery Lia Rumma. Inside a small, square room like a shrine within the booth, visitors found eight monochromatic paintings arranged so that at times they resembled light boxes; the effect was simple but mesmerizing.

The general picture of the fair was either “good” or “very good” judging by the sales figures released to the press, and as always vastly unequal, with mega galleries making millions while small galleries barely covered their costs. You would think that collectors are not feeling the pressures of the world right now, but nothing could be further from the truth. Buyers at Art Basel were being cautious and putting their money on work that is not only safe, but aesthetically pleasing and free from the inexorable demands of reality today. Art dealing with politics was evident only at the level of artists like Mona Hatoum and Doris Salcedo, but for the most part it was absent. On the other hand, the artworks consisting of mirrors and gold from earlier years were also gone.

The people of Basel complain endlessly about the fair, which is the best and the worst week of their year. There are the endless parties and special events, but many are exclusive VIP events that are inaccessible to the locals. One day last week, while riding the public tram from the border with Germany (where many fairgoers stay because prices across the border are much lower), I heard the morning news broadcast in German mention that Art Basel had invited a criminal dealer to Switzerland — a reference to the legal troubles of Helly Nahmad. However, the Swiss are no strangers to the speculation, money hoarding, and limited access to information that are the rules of the art world game. During one of the week’s most coveted events, the breakfast preview of Art Basel, a local banker remarked that the banking sector is very interested in Iran and loves Arab and Russian clients because it’s easier to deal with them, whereas US regulations have caused many Swiss banks trouble.

AA Bronson installation at Art Basel 2016, presented by Esther Schipper

Regardless of the criticism leveled at it — much of it justified — Art Basel is for the most part actually about art and, however monotonous it may be, the fair is a high-quality spectacle. Its additional sections like film, Parcours, or the talks program add some flavor, but the tectonic plates of the fair move according to the results of the central ring of the first floor, with Unlimited evolving from a special section into a largely commercial venue for work that is pricey and oversized. This type of work is as popular as ever, perhaps even more so, but amid last week’s feeding frenzy for familiar modernists one could also read the attitudes of the global elite toward the turbulences of the world, which can be felt even in Switzerland.

Neutrality and remoteness are no longer possibilities. Walking through a working class neighborhood where Turkish mixes with the Swiss German dialect, I discovered a neon installation hanging in a small independent art space in support of the admission of refugees. The week of the fair, a local radio station hosted a heated debate about Brexit and the future of the European Union. In a conversation with Jochen Volz, the curator of the upcoming São Paulo Biennial, and Protocinema’s Mari Spirito at the Kunsthalle, we discussed whether there is a place left for art at all anymore. Surprisingly, judging by events in many distant geographies, it seems that in many situations conversations about and around art have become substitute for a public domain that is forever receding under the pressure of capital. The art world is only a microcosm of what is happening in the real world; it may be helpful for understanding the global atmosphere, but it’s not the whole picture.

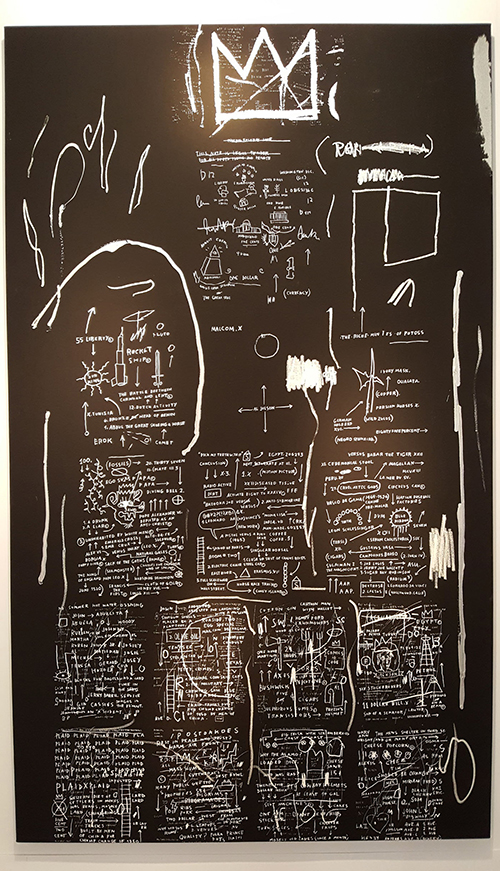

Jean-Michel Basquiat painting, presented by Van de Weghe (click to enlarge)

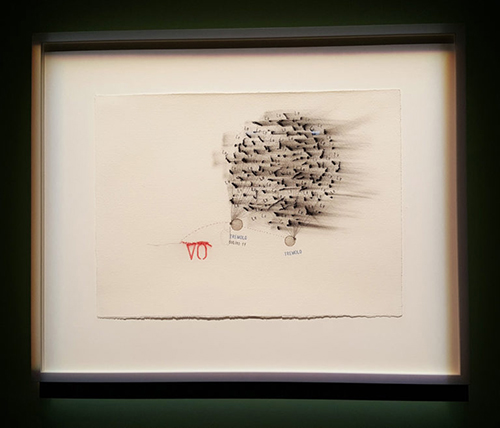

A work by Samson Young, presented by Galerie Gisela Capitain and Team gallery

Sol LeWitt, “Irregular Tower” (1999), presented by Alfonso Artiaco

Sol LeWitt, “Irregular Tower” (1999), presented by Alfonso Artiaco

The author was invited to speak on a panel at Art Basel which helped cover his expenses to attend the event.

Art Basel (Messeplatz 10, 4058 Basel, Switzerland) took place June 16–19.