In Brooklyn, a Forum Focuses the Fight Against Displacement

Panel discussion during the Brooklyn Community Forum on Anti-Gentrification and Displacement, Brooklyn Museum, July 24, 2016 (photo by Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic)

The road that led to last week’s Brooklyn Community Forum on Anti-Gentrification and Displacement at the Brooklyn Museum was long and winding, but its starting point is very clear. It began in early November of last year, when the Brooklyn Anti-Gentrification Network (BAN) published a petition demanding that the Brooklyn Museum, then newly under the leadership of Anne Pasternak, cancel its agreement to host the sixth annual Brooklyn Real Estate Summit.

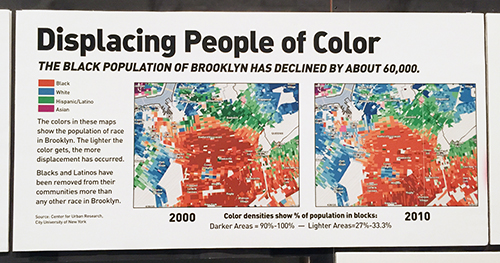

The summit brings together real estate developers, investors, owners, and others involved in the business to discuss ways they can increase their profits in the borough. It’s not hard to see why its presence at a cultural institution owned and partially funded by the city — that also happens to be located in one of New York’s most rapidly gentrifying areas — was so inflammatory. In a morning panel unironically titled “There Goes the Neighborhood,” the speakers were scheduled to discuss the following: “Discovering undervalued properties with a more valuable future use is an art and a science that can yield untold–and sometimes unexpected–riches.” The meaning there seems clear: remove rent-regulated tenants (who, in the areas surrounding the museum, are overwhelmingly low-income people of color), flip the building to market rate or condos, and reap the “untold riches.”

As Imani Henry, an artist as well as the founder and lead organizer for Equality for Flatbush, which started BAN, noted in our conversation, the choice to publish the petition grew out of long-standing local efforts to counter gentrification, specifically to resist those who “occupy and militarize our neighborhoods and push us out.”

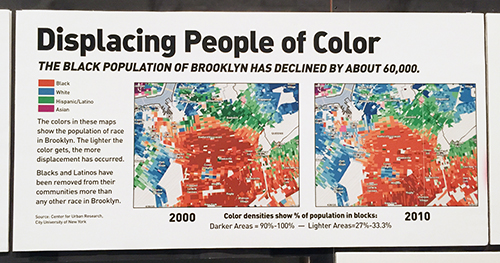

Detail of “A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing” (2016), created collectively by various artists, on view in ‘Agitprop!’ (photo by author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

Because the petition was aimed at a prominent arts space, a number of other artists, most of them white and organizing for affordable studio/work spaces, took notice and wrote their own letters. Following that, Pasternak issued a short public letter but did not cancel the agreement with the summit. It’s worth noting that, although Pasternak said in the statement that she reached out to “[artist] Sarah Quinter and other community organizers,” she never approached BAN, the group that issued the original petition, and Henry was not among those who organized last week’s forum, though BAN did participate.

In response to the museum’s inaction, protests were organized for the day of the summit, and eventually the museum agreed to a series of meetings, which took place over several months and involved a varied group of artists and community organizers. Beyond the original demand to cancel the rental contract with the summit, other requests included:

- Convening a forum on affordable housing at the museum

-Changing the museum’s rental policy to better reflect its mission

-Removing David Berliner from the museum’s board — Berliner is the CEO of Forest City Ratner, the real estate developer responsible for the Atlantic Yards project, now rebranded as “Pacific Park,” which displaced hundreds of local residents, has been met with numerous lawsuits, and has failed to deliver the number of genuinely affordable housing units it promised

-Placing a new artwork in the Agitprop! show reflecting local community struggles against displacement

-Payment for any artists or speakers who would contribute to the making of that piece or speak at the forum

The meetings stretched on, and according to artist and forum co-organizer Betty Yu, the museum was not very responsive through much of the process. In addition, some of those initially involved in organizing dropped out or realigned themselves for a variety of reasons. In my conversation with artist and forum co-organizer Antonio Serna, he explained that there was frustration about the lack of people of color involved, to the extent that some members of Arts & Labor (an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street) created the Artists of Color Bloc during the process.

“A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing” (2016), created collectively by various artists

(photo by author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

In April 2016, the first sign of progress came when the collectively created artwork “A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing” was added to the Agitprop! exhibit. But there was little movement on the forum itself until a second round of protests at the museum in May, which focused both on Agitprop! and This Place, an exhibit featuring photographs of Israel and the occupied West Bank that was funded by many pro-occupation groups and individuals.

Following those protests, the museum brought an outside mediator into a late May meeting with the protesters, who were continuing to push for an anti-gentrification forum. From there plans began to fall into place, with the museum agreeing to host the event, partially cover honoraria for speakers and incidental costs, and provide staff support. The forum was scheduled, a time and date were set — and then, at the last minute, it looked like everything might fall apart when the museum announced it would close that weekend due to air-conditioning issues. However, the event was soon rescheduled. As Yu noted, the realization of the event was no act of benevolence on the part of the institution. “The reason this forum happened was because people pushed for it,” she said.

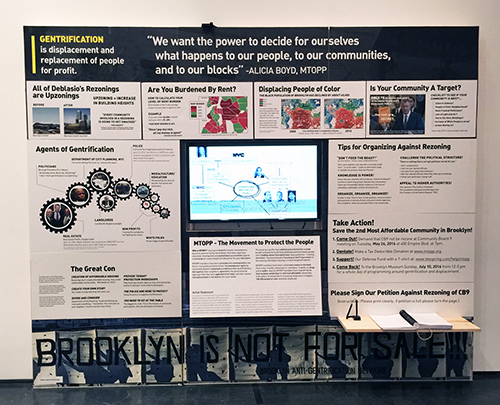

So, after all of that effort, what was the forum? In essence, it was a daylong series of panels, performances, roundtables, information-gathering sessions, and organizing opportunities representing a host of different groups and goals, in three different spaces of the museum. The most accurate agenda can be found on the website of the Movement to Protect the People, a group founded by forum co-organizer Alicia Boyd.

Somewhat inexplicably, the museum did not send any senior staff to participate in the event, and Anne Pasternak was not seen at all. But perhaps more concerning was an incident that occurred near the end of the day, as some participants were hanging a few posters. A member of the museum staff told them that they couldn’t put the posters out because one of the conditions for the event was that there be no direct criticism of the institution. The museum did not respond to two emails I sent requesting comment on this and other points. It’s also unclear why the organizers would have agreed to this. When I spoke to Yu about it, she told me that everything was communicated verbally, and nothing substantive was put into writing. With so many people involved and such a protracted process, it’s unclear who actually agreed to what. The simple fact that such a restriction was put forward by the museum, however, raises serious questions about its actual willingness to engage local communities, as well as its political and ethical commitments.

Roundtable discussions during the Brooklyn Community Forum on Anti-Gentrification and Displacement, Brooklyn Museum, July 24, 2016 (photo by Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

Despite this, and despite impressions that the event was a bit disjointed (unsurprising, given the array of different groups involved), there were tangible outcomes worth noting.

Both Henry and Yu felt that just being able to have the space for a day and bring the community into the museum to discuss these issues was itself a success. “We’ve never had a forum quite like this, at this scale,” said Yu. And the protests leading up to it did succeed in drawing a good deal of attention to displacement in the neighborhood and the role the museum could be playing in the community.

In addition, the event offered a chance to build greater awareness of the organizing that’s already happening in Brooklyn around gentrification. Yu, Henry, and Ana Orozco of UPROSE, who spoke on one of the afternoon panels, all noted that they saw many new faces, a large number of whom signed on to local campaigns or reached out following the event. Having different groups and organizers together in one place, interacting with each other and the public, was a rare opportunity to build solidarity among those fighting related struggles across the borough and the city.

Detail of “A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing” (2016), created collectively by various artists

(photo by author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

That said, the role of artists within the forum and in displacement struggles more broadly is uncertain. Everyone I spoke with offered critiques of white artists and new residents who adopt “white savior” mentalities or don’t take the time to learn about their neighborhoods before suggesting changes. Artists have long been the first wave of gentrifiers across the city, and in fighting for affordable work space, they’ve sometimes failed to link their own struggles to those of long-term residents fighting to keep their homes and jobs. In addition, with more resources and better access to media, many newly arrived artists have contributed to the erasure of cultural and artistic production that existed in their neighborhoods long before them.

UPROSE, which calls itself “Brooklyn’s oldest Latino community based organization,” knows this tension well, as it is based in Sunset Park. The group’s primary work right now is advocating for the creation of well-paying manufacturing jobs for area residents in the energy sector along the Sunset Park waterfront — a place known to many Hyperallergic readers as the site where a group of primarily non-resident artists were fighting the loss of studio spaces in Industry City not long ago. But these struggles do not have to be at odds with one another. “For the most part [artist allies] have been very receptive to constructive criticism and to support us instead of being a hurdle,” Orozco noted.

Talk of gentrification and displacement can often feel daunting and, as Henry pointed out in our chat, inevitable. Feelings of powerlessness, guilt, and fear — plus real threats of violence, criminalization, and home loss faced by many poor people of color — conspire to push those on the ground to fight with and avoid one another, rather than working together to resist developers, unfavorable city agreements, and the racist policing and incarceration that are driving so much gentrification.

Henry noted that one of the most important moments of the forum for him came during the roundtables, when he and others shared stories of how they became activists and helped stop people from being displaced. These stories gave attendees a sense that they can and should get involved, because successes are possible. “Equality for Flatbush’s number one goal is to keep people in their homes,” says Henry. “Because if we can keep them in their homes, we give hope to others, and then we can stay there and fight.”

What role the Brooklyn Museum will play in all of this remains unclear, particularly as it finds its footing under new leadership and as more wealth moves into and tries to influence the surrounding neighborhoods. What is clear is that many local groups remain strongly committed to pushing for a future for those neighborhoods that places local voices and interests first. As Orozco put it, “We have to be diligent. When it comes to development, instead of talking about it being community-centered, I would rather we talk about it being community-driven.”