SÃO PAULO — Critics in major Brazilian newspapers have been calling the 32nd São Paulo Biennial too “politically correct,” all ideas and no art.

Lais Myrrha, “Dois pesos, duas medidas” (2016) at the São Paulo Biennial (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

SÃO PAULO — Critics in major Brazilian newspapers have been calling the 32nd São Paulo Biennial too “politically correct,” all ideas and no art. The response has been a conservative and nostalgic one — for the days when this historical biennial showed the great American and European modernists — while the US press has tended to glorify this biennial’s theme, Incerteza Viva or “Live Uncertainty,” by transposing it onto Brazil’s wretched political climate. It’s true that at the biennial’s preview, participating artists manifested themselves with shirts bearing slogans like, “Elections now” and “I want to vote for president” — over one third of the biennial’s artists are Brazilian — and with or without a biennial, politics is inevitably on everyone’s mind. And at least one artwork, a lounge-like space of benches and beds that intends to create a “temporary autonomous zone,” by Oficina de Imaginação Política, directly responds to the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff, with surrounding chalkboards and posters blaring “Fora Temer” (“Out Temer,” the current president) and “There was a coup,” among other pronouncements. But to analyze the biennial — a gathering of 90 artists from around the world, not all contemporary — in this light feels at times forced and even reductive.

A detail of Oficina de Imaginação Política’s installation. The signs read: “The World Cup Happened,” “The Coup Happened,” “The Olympics Happened,” “There Is Censorship.”

As for the curators, they see this year’s biennial as representative of art’s embrace of uncertainty and experimentation, and encourage today’s tumultuous world to take some advice from artists. The hope, curator Sofía Olascoaga told me, is “to move away from our rhetoric of crisis and move toward a place of possibility.” She began by explaining, “There is a need to change our daily lives, from the drastic political shifts to the impact in our daily economic lives … and the way we understand life in this series of changes.” The chosen artworks, the curators believe, offer the tools for this new kind of understanding.

The discursive nature of the biennial, like many others before it, can get not only a little exhausting, but vague — cluttering the mind and eye rather than clarifying them. The São Paulo biennial was not always structured this way. When it began in 1951 it was a bit like the Venice Biennale, divided by nation. The change came in 1981, with the 16th biennial, when it, as journalist Leonor Amarante put it, “definitively abandoned the geographical structure and took on the challenge of analogies of language.” At the time, artists and critics were divided, with some believing the new structure would bring more flexibility while others, like the renowned Brazilian critic and curator Aracy Amaral, perceived the change as an excuse to employ pedantic and meaningless jargon.

Amaral had a point. But the shift also makes sense to me: art itself has become increasingly discursive. More than an aesthetic, artists have shared social, economic, environmental, and political concerns. Here, at the biennial, it seems that in our uncertainty, regret, and despair about the state of the world we’ve tried to revert to old ways, go back in time, even while we can’t or often don’t fully know what that would entail.

Michael Linares , “Museu do Pau” (“The Museum of the Stick”) (2013–16) (detail)

Michael Linares , “Museu do Pau” (“The Museum of the Stick”) (2013–16) (detail)

In “Museu do Pau” (“The Museum of the Stick”) (2013–16), the Puerto Rican artist Michael Linares collects, nails, and suspends various objects that are literally composed of sticks or are stick-like, among them a skewer, bow-and-arrow, matches, markers, a spear, toothbrush, broom, and Catholic cross. The installation stresses human craft and our ancient use of wood, mixing objects continuously used throughout time. Jonathas de Andrade, a contemporary Brazilian artist who has been gaining international acclaim, similarly documents an old tradition, that of killing fish, which fishermen in the northeast of Brazil still practice: pulling the fish from the water with both hands, they hold the convulsing animal in an intimate, caring embrace, petting it until it dies, like putting a crying child to sleep.

Jonathas de Andrade, “O peixe” [The Fish] (2016)

There are also artists here who attempt to rescue or make visible a past that has been altogether obliterated, altered, or betrayed. In “Rota do tabaco” (2016), Dalton Paula visits cities in Brazil and Cuba with colonial histories in the tobacco industry and where many of the inhabitants are the descendants of African slaves. Paula registers the inheritance of this past in his ceramic plates, which are generally used for food or in Afro-Brazilian rituals, and paints black figures in white clothing going to school, playing music, and socializing. The bodies climb out from the depths of the bowls, which one needs to bend over to see, as their lives zoom into focus.

Dalton Paula, “Rota do tabaco” (2016) (detail)

Nearby, the Portuguese, Berlin-based artist Grada Kilomba, tells a three-part story, using white text projected onto black screens, about the experience of being silenced and judged as a black woman. The sentences are broken, appear and disappear in fragments, stressing labels she’s been associated with: murderer, drug dealer; the adjectives used to describe “them” — “facts,” “knowledge,” — versus “us,” “subjective,” “experiences.” “Why do I write?” the question appears and slides off the screen like a passing reflection in dark waters, a beat thrumming in the background. Out of “obligation.”

Are these the works that the Brazilian critics have found “politically correct”?

Bené Fonteles, “Ágora: OcaTaperaTerreiro” (2016) (exterior view)

I admit that just because art probes virtuous or overlooked subject matter doesn’t make it good. There are, as critics outside of Brazil have also noted, works that bore and disappoint in their psychedelic or familiar spiritual attitudes, including two huts, one inhabited by sculptures and manifestoes associated with the idea of “being Brazilian” by Bené Fonteles and another by Pia Lindman that is intended to transmit the healing practices of a Finnish community from the European Middle Ages. When I was told that the latter artist would give me “a treatment focused on joints and bones” I perhaps naively expected to undergo some kind of therapy in the mud hut, but instead was confronted with an empty bamboo medical table and cluster of plants. This is not the first time an indigenous hut has been transplanted into the biennial space. In 1975, a man from the Aritana indigenous community along the Xingu River built a hut where, once inside, the visitor heard the daily sounds of the Xingu tribes. In fact, with so much talk of indigeneity this year, there is only one work that involves Brazilian indigenous artists, a 1986 project by Vídeo das Aldeias that trained indigenous filmmakers.

Pia Lindman, “Nose Ears Eyes” (2016) (interior detail)

I was not the only one at the biennial left somewhat perplexed by these encounters. In Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas’s “Psychotropic House: Zooetics Pavilion of Ballardian Technologies” (2015–16), a man appeared to be fashioning a clay bowl in a plastic tent that warned, “Do not enter.” A label told me the artwork had something to do with mycology, as the objects were partly made from fungus. The idea intrigued me, but I struggled to connect with and parse what was happening, standing on the outside of a series of tents filled with similarly gray, unfinished bowls and vases, until a group of curious girls unabashedly tried reaching the man through the plastic, asking, “What are you doing?” The man eventually emerged and explained, “The idea is to make a live object.” I like the idea, but, like a number of artists featured here, I was left feeling that there was a basic lack of skill in or concern for storytelling.

When I asked Olascoaga what the local reception has been, she said that much of the local criticism “has to do more with a general discussion on the languages and practices of contemporary art rather than with a keen examination of the biennial’s proposals.” She continued, “There is a kind of claim to have more recognizable and stable plastic or formal languages of art.” Indeed, this is no longer the São Paulo biennial of Légers, Picassos, Pollocks, and Calders. Incerteza Viva serves as a message to these critics: Your way of perceiving the world and the responses to it is outdated and you need to get with the program.

This is largely true. The art world is no longer fixated on white Europeans and Americans, or aesthetically pleasing work, and nostalgic criticisms reveal a level of disengagement. But I wondered whether the art in the biennial offered the tools I wanted or needed for renewed understanding.

Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas, “Psychotropic House: Zooetics Pavilion of Ballardian Technologies” (2015–16)

One of the outstanding works is Lais Myrrha’s dominating installation that rises to the third floor and is symbolic of the exhibition as a whole: two pillars, one neatly layered with native materials (woody vines, straw, and logs) and the other with construction materials typical of Brazil’s buildings (bricks, cement, iron, tubes, and glass), delineate two ways of life. But both are impenetrable structures, titled “Dois pesos, duas medidas,” or “Two weights, two measures.” As I came across them upon each loop of the Oscar Niemeyer building, the two pillars seemed to say that both our past and present have become inhabitable. I was left in an uncertain place, caught between time periods and worlds, no longer sure of where I stood.

Frans Krajcberg, “Gordinhos, Bailarinas and Coqueiros”

Eduardo Navarro, “Sound Mirror” (2016)

The Ibirapuera Park reflects into the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo space

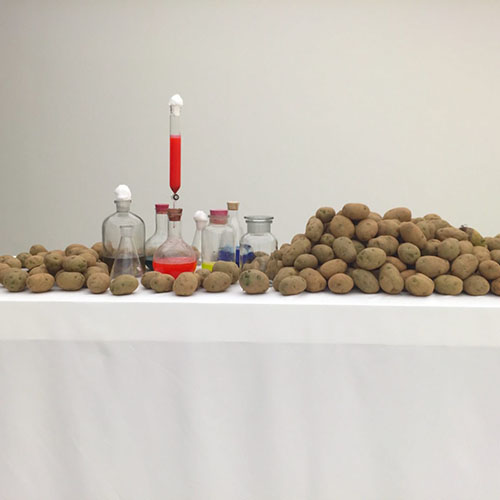

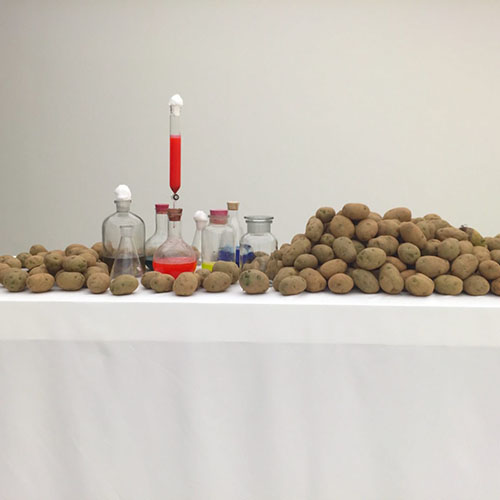

Vítor Grippo, “Naturalizar al hombre, humanizar a la naturaleza, or Energia vital” [Man Naturalization, Nature Humanization, or Vegetal Energy] (1977)

The entrance to the 32nd São Paulo Biennial

The 32nd São Paulo Biennial, Incerteza Viva (Live Uncertainty), continues at the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo (Ibirapuera Park, Av. Pedro Álvares Cabral, Ibirapuera, São Paulo) through December 11.