The urtext of emoji, a series of 176 pixellated pictograms, was released for cell phones in 1999 by Japanese tech company NTT DOCOMO. Since then, emoji has become a global visual language so popular that some fear it will bring about the “death of English.” It probably won’t, but early emoji will secure a place in the canon of contemporary design: the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) announced today that it will add the original set of 176 emoji to its permanent collection.

The impetus for the acquisition goes back to MoMA’s founding principles, which stipulated that its collection would include humble, everyday designs alongside fine art. “The museum was founded on this Bauhaus idea of all the arts coming together to improve people’s lives,” Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of the Department of Architecture and Design, told Hyperallergic. “So collecting design was part of the mandate from the beginning — including stage design, costume design, and architecture — but especially design that becomes part of people’s everyday lives. The kind of humble masterpieces that range from the Post-It note to the paperclip; priceless everyday objects that people cannot live without. And we certainly cannot live without the emoji anymore.”

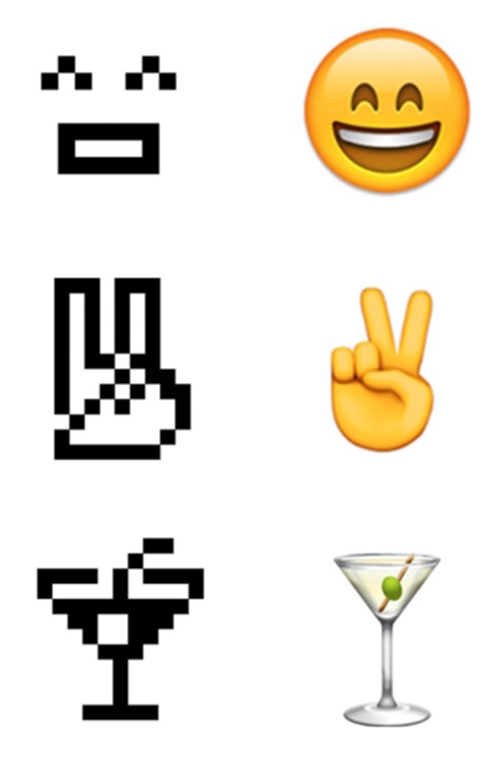

These 176 retro pictograms were the ancestors of the almost 1,800 standardized emoji available on today’s mobile messaging apps. Featuring standard pictogram fare (hearts, smiley faces, astrological signs) as well as a few random, whimsical objects (snowmen, top hats, a rocking horse), the original emoji set was designed by Shigetaka Kurita. Each was rendered on a grid of 12 by 12 pixels, in just one of six colors — black, red, orange, lilac, bright green, and royal blue. As inspiration, Kurita drew on manga, Zapf dingbats, and emoticons of the typed-out variety. “They are so amazingly beautiful and expressive,” Antonelli said. “The emojis are the humble masterpieces of the digital world.” The curator is an avid emoji-user herself; her favorites include “fireworks, fire, hearts, the little devil, explosions, and frogs, because they’re my favorite animal.”

In The Story of Emoji, a book recently published by Prestel, Jeff Blagdon explains why emoji took off in Japan after the mainstreaming of digital communication:

In Japanese culture, personal letters are traditionally long and verbose, full of seasonal greetings and honorific expressions that convey the sender’s goodwill to the recipient. The shorter, more casual nature of email was at odds with this tradition. The absence of [body language] cues in emails and texts meant that the promise of digital communication — being able to stay in closer touch with people much more easily — was being offset by an accompanying increase in miscommunication.

Kurita designed emoji, then, to allow for the translation of non-verbal communication cues into digital messaging. This turned out to be useful for the rest of the world, too; in 2010, Japanese emoji were translated into Unicode. In 2011, Apple added emoji to its iOS messaging app, setting off the global emoji explosion. “Filling in for body language, emoticons, kaomoji, and emoji reassert the human in the deeply impersonal, abstract space of electronic communication,” writes Paul Galloway, MoMA Architecture and Design Collection Specialist, in a Medium post.

Shigetaka Kurita, NTT DOCOMO, original Emoji (1998–99) versus today’s emoji (2016)

This is only the latest in a recent series of MoMA acquisitions of digital objects that defy conventional understandings of museum-worthy art and design. In 2010, the museum acquired the @ symbol, a game-changing move that, as Antonelli said, “relies on the assumption that physical possession of an object as a requirement for an acquisition is no longer necessary.” Soon after, in 2012, the museum acquired 14 classic video games, including Pac-Man and Tetris, as part of a “new category” of art; and in 2014, acquired Björk’s Biophilia app, the first downloadable app in its collection.

The @ sign acquisition was met with some bafflement, because “it was much more conceptual,” Antonelli said. “It was hard for people to get it. But with emojis, people can relate to the fact that they’re design objects.” Galloway explains why the original emoji set is culturally significant enough to deserve a place in the collection:

Shigetaka Kurita’s emoji are powerful manifestations of the capacity of design to alter human behavior. The design of a chair dictates our posture; so, too, does the format of electronic communication shape our voice. MoMA’s collection is filled with examples of design innovations that radically altered our world, from telephones to personal computers to the @ symbol. Today’s emoji (the current Unicode set numbers nearly 1,800) have evolved far beyond Kurita’s original 176 designs for NTT DOCOMO. However, the DNA for today’s set is clearly present in Kurita’s humble, pixelated, seminal emoji.

The acquisition will be celebrated in an upcoming installation in MoMA’s lobby, opening in early December. They’re still figuring out how to display the emojis; Antonelli is tossing around ideas for analog displays, like silkscreened prints or emoji wallpaper, as well as displays on screens. This analog-digital mix will be a reminder of the fact that pictograms aren’t new. “I think that emojis existed in Ancient Egypt and the cave,” Antonelli said. “If anything, this is a rebirth.”