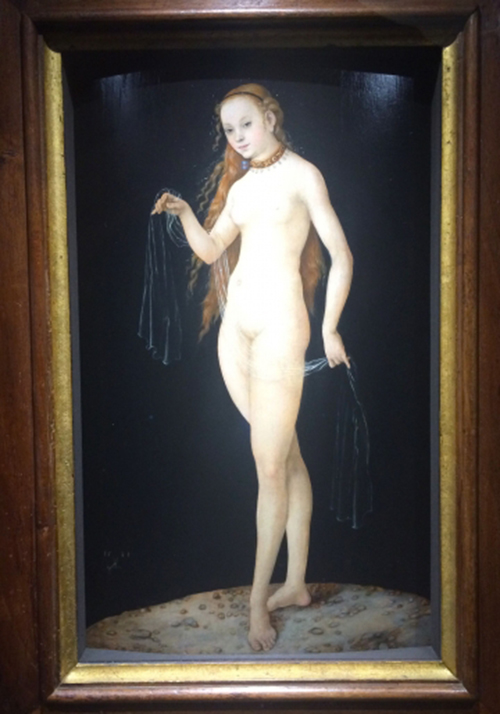

Noce reported in the Art Newspaper that the Cranach came onto the market in 2012 and was sold to the Princely Collection in 2013 in good faith by the Colnaghi gallery, which stated that it was discovered in a Belgian collection, having apparently been there since the middle of the 19th century. Colnaghi also said the work was attributed to Cranach by three leading specialists: Werner Schade, Bodo Brinkmann, and Dieter Koepplin. According to Noce, several experts doubted the authenticity of the “Venus,” citing issues with the signature and the state of the wooden panel. Ahead of its Old Master auction toward the end of 2012, Christie’s commissioned technical analysis which raised “concerns,” including the “rather coarse nature” of the azurite found in the pearls Venus wears and the anachronistic presence of titanium white (though this could have been the result of later restorations), requiring “further research.” Christie’s passed on the purported Cranach, which was eventually offered to Sotheby’s and other auction houses, all of which declined the sale.

Nevertheless, the Liechtenstein Princely Collections remain confident of the Cranach’s authenticity. Its director, Johann Kräftner, released a statement earlier this month citing the reports of Cranach experts Koepplin and Schade; two restoration reports commissioned before the acquisition by the Princely Collections in 2013, and subsequent restoration reports; dendrochronological analysis commissioned by the Collections after the acquisition and carried out by Peter Klein at the Zentrum Holzwirtschaft of the University of Hamburg; and an expert report received from Claus Grimm, art historian and Frans Hals specialist after the seizure of the painting. “Any divergent opinions resulting from recent analysis instructed by the French authorities can and will be refuted, point by point, as part of an ongoing investigation,” Kraeftner’s statement says. “We will not make any other public comment while the investigation in ongoing.”

As the Liechtenstein Collections reaffirm their conviction of the Cranach’s authenticity, there is nothing to suggest that they, Colnaghi, or Ruffini were acting in anything other than good faith in handling the piece. What is odd, however, is that it is also the subject of a lawsuit ongoing since 2014. The suit details how the painting changed hands through two middlemen before ending up with Colnaghi, with the original seller suing the middlemen for breach of trust once the panel, originally listed as the work of an unknown artist, had been “asserted” as a Cranach and sold to Liechtenstein for a considerably larger sum. Ruffini’s lawyer, Philippe Scarzella, simply told the Art Newspaper that his client had found paintings “that could have been done by Jan or Pieter Breughel, Van Dyck, Correggio, Bronzino, Parmigianino, Coorte and others,” and that they were all put on sale.

Scarzella added that an investigation relating to the seizure of the alleged Cranach included a half-dozen other works, among them a portrait attributed to Hals, a “David with the head of Goliath” attributed to Gentileschi, and a portrait of Cardinal Borgia after Diego Velázquez. Sotheby’s confirmed that it had received consent from Weiss to inform Hedreen, the buyer of the purported Hals portrait, of a potential issue with the work; while dendrochronological tests had been carried out in 2011, newly commissioned “materials analysis,” including pigment examination, led the auction house to the verdict that it was a forgery.

While Sotheby’s has reimbursed the collector, according to the Art Newspaper, Weiss has not yet refunded his 50% share of the sale, declaring that further analysis is required. A spokesperson for the Weiss Gallery stated that “[Mark] Weiss, strongly believes, as do others in the museum and scientific world, that more forensic analysis needs to be done before making a final judgement on this painting.” Indeed, when the painting “emerged” on the market in Paris back in 2008, it was the subject of a full scientific analysis by France’s Centre for Research and Restoration before the Louvre and several supporting Hals scholars mounted a €5-million (~$5.4 million) campaign to purchase it. After the campaign’s failure, it was sold to Weiss.

“David contemplating the Head of Goliath”

The disputed Gentileschi, sold by Weiss sometime around 2012 according to the dealer’s website, was loaned by its current owner to the National Gallery for the 2013 exhibition Making Colour. At the time, it was hailed as a recent discovery, remarkable for having been painted on a lapis lazuli ground. Despite the newness of the piece to the market, its unusual material, and its striking similarity to a painting by Gentileschi of the same name in Berlin, no technical analysis was conducted on the piece by the National Gallery before it displayed the work. The Gallery said in a statement sent in early October:

The National Gallery undertakes due diligence research on all works coming on loan as well as undertaking an assessment of condition (however a full scale technical examination is not generally performed). When there is no published provenance for a work – as there was not in the case of David with the Head of Goliath – then we gather as much documentation and information about its history as possible. Our decision to take a painting on loan is based upon this evidence and our professional judgement. In the time the painting was at the National Gallery we had no obvious reasons to doubt that “David with the Head of Goliath” was a work by Gentileschi.

The cases of the purported Gentileschi, Hals, and Cranach paintings raise a number of issues for the Old Masters market, to say nothing of the impending revelation of dozens more suspected forgeries, as predicted by the Mail on Sunday. The scandal calls into question the authority of major institutions — Sotheby’s, the Louvre, the National Gallery, and others — as well as the dealers who handled the pieces. Ruffini has suggested that it is the duty of museums to authenticate works, insisting that, as a “collector,” he is not liable for attribution.

There is nothing to suggest at this point that any of the above parties knowingly handled a fake. It is the duty of museums to present to the public artworks with attribution determined by the best available knowledge, exercising due diligence in terms of researching provenance and, where necessary, conducting material analysis. Nicholas Penny, in his tenure as director of the National Gallery, purposefully replaced “Attributed to” in captions and wall texts with either “by,” “Probably by,” or “Perhaps by.” In the art market, authenticity has enormous implications on selling value. Just this week, during TEFAF in New York, there was much interest in a bust of Jesus bought by scholar and dealer Andrew Butterfield in London for a reported £99,000 (~$121,000), who, having reattributed the work to Gian Lorenzo and Pietro Bernini, is now asking around $10 million for it.

It is also possible that technical analysis is not an infallible method of attribution. The Louvre narrowly missed out on purchasing the now-disputed Hals; prior technical analysis by France’s Centre for Research and Restoration supported the attribution, while subsequent reassessment by Orion Analytical commissioned by Sotheby’s concluded that it was a forgery. There is also the need for academic assessment: a combination of the expert eye and research into provenance. The National Gallery, despite the lack of provenance before the 1990s attached to the disputed Gentileschi, evidently was sufficiently satisfied in its research to forgo technical analysis. As of this writing, Sotheby’s had confirmed that it was sending the disputed Parmigianino “St. Jerome” for analysis.

That the possibly fake Hals and Cranach paintings passed some technical analyses and not others indicates an unprecedented sophistication in their forgery. If they came from the same source, and the names cited by Ruffini’s lawyer are all examples to be further investigated, then this may be the work of a seriously skilled and prolific forger. Art historian Bendor Grosvenor speculated that this hypothetical forger may be “the best ever,” and that the effect on the Old Masters art market is hard to overestimate. It is telling that most galleries are remaining tightlipped about the situation, with many refusing to comment further than has been cited here. Until the list of 25 suspected forgeries has been revealed and fully investigated, galleries are proceeding with extreme caution.

It could be said that the “discovery” of supposedly lost or previously unknown paintings is the holy grail for most art dealers — Philip Mould bases an entire BBC series, Fake or Fortune, around this excitement — and we have seen just this month how a new, more canonical attribution can massively inflate the asking price for a work, as in Butterfield’s newly attributed Bernini. In the unfolding Old Masters scandal, the actions of Sotheby’s and the National Gallery are especially significant as major institutions having to do damage control after having unwittingly handled dodgy works. These cautionary tales illustrate how the excitement of “newly discovered” supposedly old works can blind people to obvious red flags like lack of provenance and conflicting forensic analysis. One need only think of the prolific career of Wolfgang Beltracchi, who churned out fakes in every conceivable style and genre, to imagine the chaos that may infiltrate the art market if a new master forger is found to be at work.