Former gallerist Carlos Rivera has devised a system he says will help inexperienced collectors come out ahead

Sunday dinners at Carlos Rivera’s home in Pacific Palisades are eclectic affairs. Rivera, a 29-year-old former gallerist and current tech entrepreneur, regularly invites a revolving cast of art world friends to partake of the elaborate meals. One recent Sunday evening the Argentinean-born Angeleno gathers a group that includes an artist, a gallery director, an advertising executive, and a Hollywood producer who has recently begun collecting art.

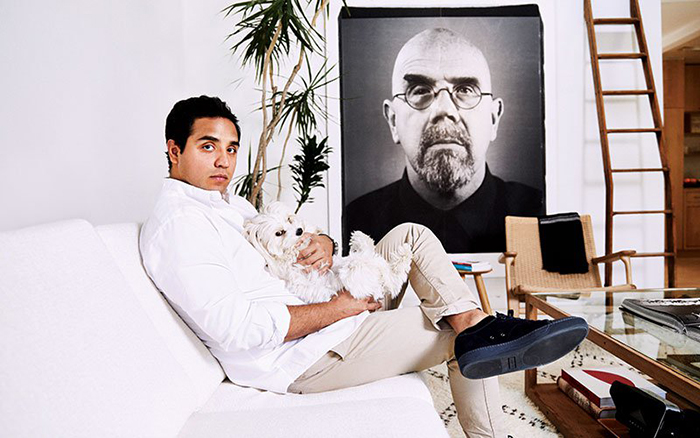

While the calendar confirms it is technically autumn, the oppressive heat of the Santa Anas belies the date. Several of the recent transplants in attendance express surprise at the winds and intense temperatures. Rivera and his girlfriend, Christina Stockton, a former professional golfer who works in commercial real estate, anchor the end of the long dining table across the room from a black-and-white Chuck Close portrait. There’s chitchat about the Netflix series Stranger Things, but talk inevitably turns to art, including how difficult it

is to persuade newly minted millionaires in San Francisco to buy anything but photography. Rivera, who bears a passing resemblance to actor Oscar Isaac, speaks softly and slowly, as if choosing his words carefully. He wants to know which artists Seth Curcio, the senior director at the contemporary gallery Shulamit Nazarian, and his wife, Julie Henson, a multimedia artist, most admired when they lived in San Francisco. They both answer John Chiara, who creates photographic landscapes with a massive handmade camera that doubles as his darkroom.

For Rivera this is more than idle chatter. As cofounder of the Web site ArtRank, he needs to keep his ear to the ground for up-and-coming artists. The site, launched in 2014, offers investment advice to subscribers—the current cap is ten—who pay $3,500 per quarter for early access to a ranking of emerging and blue-chip artists. Like a brokerage analyst’s report, it uses terms such as “buy,” “sell,” and the even more alarming “liquidate” to guide clients. ArtRank’s algorithm arrives at its valuations through a combination of publicly available data such as past sale prices, forthcoming exhibitions, and social media posts from art world influencers as well as insider advice from collectors and dealers.

While Rivera prepares a platter of paella that will go on the grill, the guests debate what he and Stockton should hang on a large, empty wall that previously held a piece by Christian Rosa. Stockton ponders putting a piece of neon art there, but Rivera insists he wants the space to remain bare. (He used to have a video installation by the bathroom featuring a naked Skip Arnold jumping out of a box, but when Stockton protested, he replaced it with ocean footage.)

Rivera knows that many in the art world find what he does distasteful. When he owned the short-lived West Hollywood gallery Rivera & Rivera, he gained firsthand knowledge of the backroom deals and anonymous auction bids that make the art world “so exclusionary,” he says. “It keeps new collectors out.” Rivera wants to arm wary novice art buyers interested in building small collections. “I saw a market gap,” says Rivera, who graduated from college during the recession and came to view tangible assets such as art as a surer bet than the stock market. “There was an opportunity to understand why something is worth what it’s worth.” Before ArtRank, Rivera argues, that analysis was entirely subjective.

Not that even he considers ArtRank’s as being the final verdict. With its relatively limited data set, the algorithm can be gamed, like when notorious art flipper Stefan Simchowitz fed Rivera information that turned out to be false and affected an artist’s valuation. Rivera has since excluded Simchowitz from the service, though the two remain friends. Simchowitz shrugs off the ban. “How do you quantify the unquantifiable?” Simchowitz asks. “It’s an oversimplification bordering on the absurd.”

Ask Rivera and he’ll argue that ArtRank could serve as a countermeasure to the power a single collector can wield if he or she decides to dump the work of an artist at auction, essentially tanking that individual’s career. “There’s value to having amateurs in any system,” Rivera says. “They are the future.”