lmost 50 years ago, Robert Smithson, along with his fellow artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and other adventurous colleagues, pioneered earthworks, an audacious — and short-lived — movement of the 20th century. Named for a sci-fi novel that Smithson read in 1967, earthworks represented a new genre of landscape art. Instead of painting a view of nature, sculptors created their own massive works outdoors on mesas, moraines and even the floor of the Mojave Desert. In 1971, Mr. Heizer told me: “You can’t really find a harsher climate than where a majority of my work exists right now. It’s in semiarid, flat, windy, heavy rainy season areas.”

Rather than using chisels, mallets or welding torches, sculptors rented bulldozers, front-end loaders, backhoes and other heavy-duty vehicles to excavate and construct these behemoths. And they found patrons to subsidize them.

“A work on this scale doesn’t end with a ‘show,’” Smithson pithily declared in 1971 in Arts magazine. Having gone to so much trouble, artists wanted their constructions to last indefinitely. And that’s what happened. Monumental works of art such as Mr. Heizer’s “Double Negative,” a long, difficult drive from Las Vegas, and Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” located along the banks of Utah’s Great Salt Lake, realized in 1970 and ’71, continue to attract thousands of visitors a year.

The original earthworks were never meant to be sold like paintings or statues. That was partly in keeping with the hippie, yippie tenor of the times. They have never come up for auction, although one sculpture fetched as high as $4 million in 2008.

How would you even sell an earthwork? I had never pondered the question until a few months ago, when I made my own pilgrimage to see “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill,” a 1971 work by Smithson in Emmen, a town in northeastern Netherlands. The only large earthwork he executed outside the United States, it is in a sand quarry on property owned by Gerard de Boer.

Mr. de Boer told me he was contemplating the sale of his quarry business, along with the lake and surrounding property on which Smithson constructed “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill.” Since his own childhood home, now a mini-museum devoted to Smithson’s earthwork, is still there, too, Mr. de Boer pictured the property possibly becoming an artist’s retreat in the hands of a new custodian.

To get to Emmen from Amsterdam, you change trains twice. The trip generally takes two and a half to three hours.

Smithson constructed his earthwork at the invitation of Sonsbeek ’71, a major outdoor sculpture exhibition. According to a news release from that year discovered in an archive in Amsterdam, “‘Broken Circle/Spiral Hill’ was originally commissioned as a temporary public artwork.” At the time, “No (written) agreements were made concerning the ownership and future maintenance of the work.”

Instead of installing art in a park designed during the 18th century, the organizers invited participants to make large constructions in places outside Arnhem, which is about 60 miles from Amsterdam. Smithson applauded the idea of making something that was not a pastoral setting.

“In a sense, a park is already a work of art,” Smithson once explained. “It’s a circumscribed area of land that already has a kind of cultivation involved in it.”

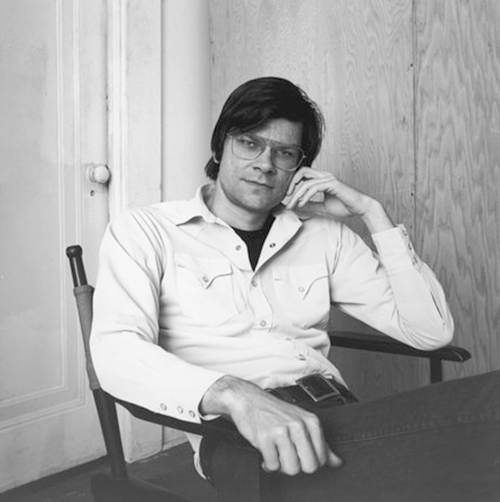

At 6-foot-3 and often dressed all in black like a character in the B-movies he watched on West 42nd Street, Smithson cut a striking figure. His prescription aviator glasses, slicked-back brown hair, blue-gray eyes and pockmarked skin completed the persona he projected. Initially, he envisioned executing a “pour piece,” which involved having a dump truck pull up to the edge of a hill and release wet concrete or asphalt that would erratically stream down the incline. Once completed, these works resembled viscous interpretations of segments of the Great Falls of the Passaic River in Paterson, N.J. But Smithson, who was born in Passaic in 1938 and raised in Rutherford and Clifton, soon learned that there wasn’t a site high enough in the Netherlands to execute this project properly.

Sjouke Zijlstra, a geographer who ran a cultural center in Emmen, told Smithson, who was 33 at the time, about a sand quarry on a lake featuring green — mineral-enriched — water. Smithson had enjoyed working in quarries in the Garden State. Now, in Emmen, he could develop on a smaller scale some ideas that related to “Spiral Jetty.”

And so Mr. de Boer, the current owner of Zand-en Exploitatie-Mij, the sand quarry, recently recalled how, when he was nearly six years old, Smithson “literally knocked on our door and asked my father if he could get permission to build an artwork in the quarry.” Though his father wasn’t interested in art, he immediately said yes. Smithson and his wife, the land-art sculptor Nancy Holt, were about the same age as Mr. de Boer’s parents; and, according to Mr. de Boer, the two couples bonded immediately.

Two weeks later, using Mr. de Boer’s father’s work force as well as his equipment, “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill” was completed. (Mr. de Boer’s father provided everything to Smithson gratis.) “Broken Circle” combines a jetty with a canal and has a boulder in its center; “Spiral Hill,” carpeted with cotoneaster, a dense green plant, since 1972, was originally composed of black dirt with white sand paths. The section in the water is a centrifugal image; the path of its earthbound companion is centripetal.

Unlike his colleagues, Smithson accompanied his earthworks with films, which made them accessible to people who couldn’t travel to see them. But his death at age 35 in a plane crash in 1973 prevented the completion of the film of “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill” until 2011. In it, we learn how Smithson’s artwork relates to both the prehistoric past as well as more recent times. The video opens with a sequence revealing a group of boulders that were transported by glaciers to their present locations during the ice age.

In the narration, Smithson mentions, “I’m not interested in excavation,” an operation that sets what he did apart from Mr. Heizer, who displaced 240,000 tons of rhyolite and sandstone when he created “Double Negative.” It is so long and deep it could hold the Empire State Building on its side. Using draglines, Smithson “carved,” as he put it, an earthwork “out of a blunt peninsula in front of a boulder.” After creating dikes, he flooded them. He wanted the water coursing through the openings to evoke the great North Sea flood of 1953 that devastated Holland, causing nearly 2,000 deaths and the evacuation of 70,000 people, and inundating 340,000 acres.

Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” on the banks of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Credit All rights reserved Holt-Smithson Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York; Photo by Tom Smart for The New York Times

Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” on the banks of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Credit All rights reserved Holt-Smithson Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York; Photo by Tom Smart for The New York Times

“Between violence and calm is lucid understanding and perception,” Smithson also said in Arts magazine in 1971. “What goes on between the raging flood and the peaceful pond? I hope to make that an aspect of the film on ‘Broken Circle/Spiral Hill.’”

With sequences shot from helicopters, Smithson also wanted people to be able to experience his art differently than if it were seen in person. In the video related to “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill,” Smithson runs on his earthworks while he’s filmed from a distance. The painter Dorothea Rockburne recently recalled how her friend Smithson had admired the scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s “North by Northwest” where Cary Grant is buzzed by a crop duster in a cornfield.

Mr. de Boer remembers that Smithson’s Dutch earthwork was, for him and his brother, “a wonderful playground.” Mistakenly believing bottles containing poetry were buried in the hill, the two boys gamely tried to find them. “There were always visitors who loved the art,” he wrote in an email to me before Christmas. To that end, there is a website so that art pilgrims can make reservations. And the family has maintained Smithson’s earthwork in pristine condition.

Asked how he would sell an earthwork, Michael Govan, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, somewhat facetiously, said recently, “You can’t give them away.”

For an institution, the weather presents a problem. Many of Mr. Heizer’s earliest works, for example, no longer exist. As for “Spiral Jetty,” for years, there was so much rain and runoff from snow in the mountains, the 1,500-foot coil of basalt rock and rock crystals was submerged. Then, for a while, it returned to optimum conditions. Because of a drought on the West Coast, the lake receded two years ago. Now you walk beside the earthwork rather than on top of it.

As head of the Dia Art Foundation, Mr. Govan accepted “Spiral Jetty” in 1999 from the Smithson Foundation and Ms. Holt, who died in 2014. Virginia Dwan, whose gallery on West 57th Street represented Smithson, Mr. Heizer and De Maria and helped finance both “Spiral Jetty” and Mr. Heizer’s “Double Negative,” donated the Heizer to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 1985. “Double Negative” is so immense, it hardly ever suffers the ravages of time and place.

With the exception of “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill” and Ms. Holt’s own “Sun Tunnels,” a land-art project near an abandoned railroad community in Box Elder County, Utah, most other classic earthworks years ago became the wards of enlightened museums so that they could be preserved in perpetuity. Even Robert Morris’s huge Observatory, which was also constructed for Sonsbeek ’71 and later reconstituted outside Lelystad, has been annexed as part of a group of six sculptures maintained by the Flevo Landscape Collection.

Who could possibly become the guardians of “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill”? Dia has been mentioned. Melissa Parsoff, the spokeswoman for the foundation, said no talks had taken place. Jessica Morgan, its director, thinks it would be a good idea. And then there’s the government of the Netherlands, which has a remarkable record for supporting the arts. It would be quite a coup to add this enchanting earthwork to the list of cultural properties it manages.

“It would be a challenge to place an earthwork,” said the dealer James Cohan, who has been the Smithson estate’s longtime agent. “And a real act of philanthropy.”