The Greatest Lovers in Art History, from Frida Kahlo and Auguste Rodin to Nan Goldin

ARTSY EDITORIAL

BY ALEXXA GOTTHARDT

Tender, teasing, ravenous embraces. Artists have long rendered wild acts of desire in their work to capture the mind-altering, body-melting effects of love. Whether forged in stone or suspended in a snapshot, lovers smolder throughout art history. Below, artists from Jean-Honoré Fragonard to Gustav Klimt to Frida Kahlo reveal the many faces of love—affectionate and ferocious, monogamous and polyamorous, fleeting and timeless.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Bolt, 1777–1778

Jean-Honoré Fragonard

The Bolt, 1777-1778

'Fragonard in Love' at Musée du Luxembourg

Jean-Honoré Fragonard The Bolt, 1777-1778

'Fragonard in Love' at Musée du Luxembourg

Fragonard loaded his ravishing paintings with sexual innuendo. In this piece, a cherubic gentleman caller bolts the bedroom door while simultaneously embracing his coy paramour, a rosy-cheeked Marie Antoinette lookalike. By combining the flourishes of Rococo style (billowing, slippery dresses and bedsheets, just-plucked flowers) and a fair amount of sly symbolism, the painter makes clear what will happen next. The bolt and the vase stand in for the phallus and vagina, respectively, while the overturned chair, with its legs in the air, alludes not-so-subtly to the subjects’ urge for a more acrobatic roll in the hay.

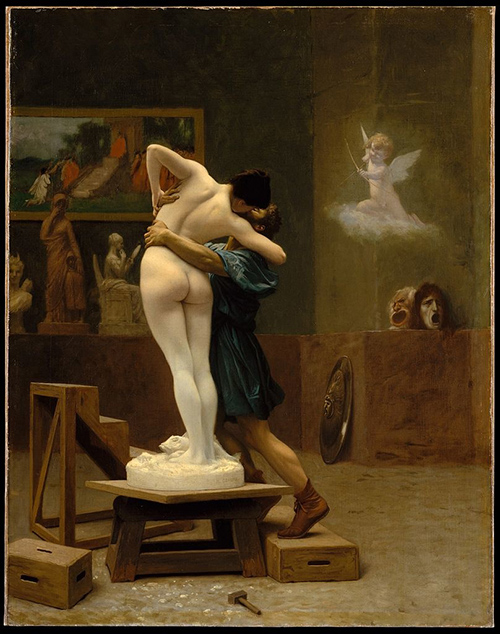

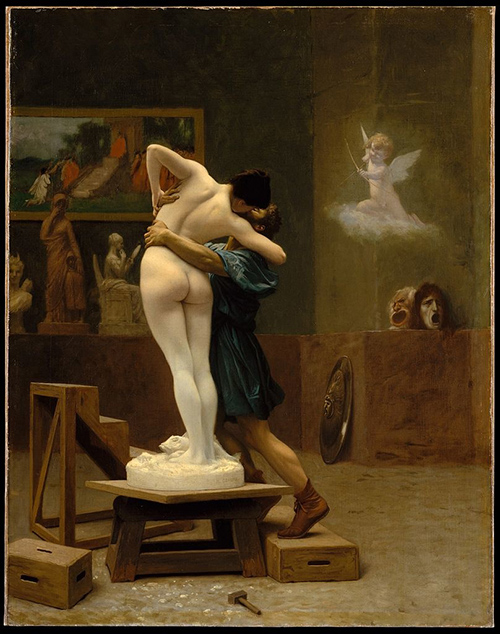

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pygmalion and Galatea, ca. 1890

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pygmalion and Galatea, ca. 1890. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pygmalion and Galatea, ca. 1890. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Here, Gérôme borrows a mythological tale of seemingly impossible love. With a little magic from the gods, however, anything can happen, as the French 19th-century academic master reveals in this canvas. It captures the momentous climax of Greek sculptor Pygmalion’s tale. Embarrassed that he had fallen madly in love with one of his female statues, he prayed to find a woman just like her. Aphrodite granted his wish later that day—represented in the painting by a happy, hovering cupid—when he landed a kiss on the ivory sculpture and she came to life.

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907

Gustav Klimt, Kiss, 1907, Belvedere Museum

In Klimt’s iconic painting, the two lovers are so closely entwined (faces overlap, hands lock) that they almost become one. The famed Austrian Symbolist enhances their physical and emotional intimacy by pulling them together within a single golden shroud. What’s more, their patterned, Art Nouveau clothes bleed into each other at the waist and wrist, as if their bodies are merging. As is typical of Klimt’s work, the realism of his subjects’ facial expressions drives home the atmosphere of the piece: blissful. Some historians posit that the couple depicted is in fact Klimt himself and his longtime partner Emilie Flöge, the last person he called before his death in 1918.

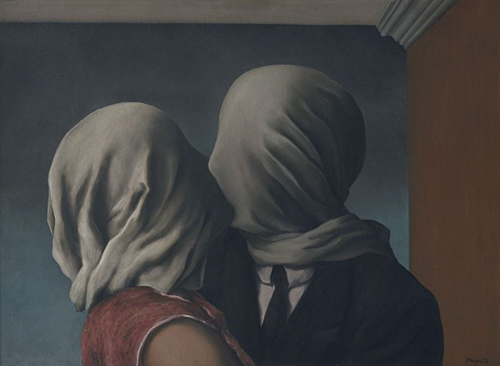

René Magritte, The Lovers (Les Amants), 1928

René Magritte, The Lovers (Les Amants), 1928, Art Institute of Chicago

René Magritte, The Lovers (Les Amants), 1928, Art Institute of Chicago

Magritte had a way of visualizing the deep, complex inner workings of the human mind and its connection with matters of the heart. Themes of frustrated desire, and other darker sides of love like obsession and idolatry, crop up across the Surrealist master’s body of work. Nowhere are they visualized more powerfully, however, than in this work. Here, two lovers are so desirous of each other that the urge—or perhaps their inability to have each other fully—is suffocating them, evidenced by their face-obscuring veils.

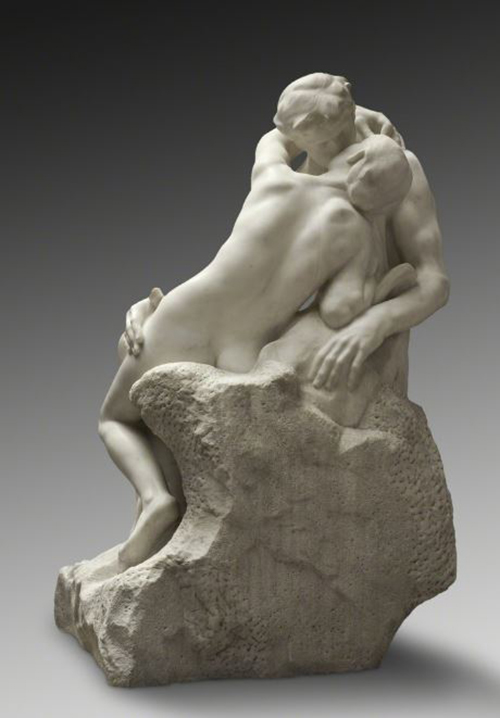

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, 1929

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, 1929, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, 1929, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Rodin’s famed marble sculpture has become a universal icon of passion; the two figures literally join at the mouth and hip, as if they are melting into each other. But the story behind Rodin’s subjects is more complex than one of a carefree rendezvous. The sculptor based the man and the woman he so expertly carved on Paolo and Francesca, two characters from Dante’s Divine Comedy. While they were both married, they shared a forbidden kiss. Rodin captures the blissful moment just before Francesca’s husband discovers the fleeting affair and kills them both.

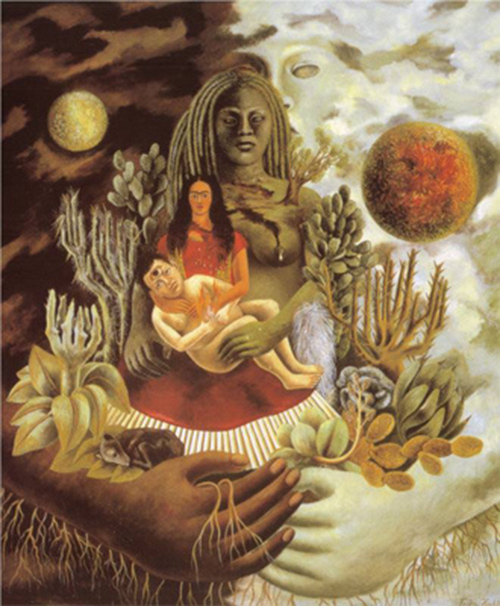

Frida Kahlo, The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xólotl, 1949

Frieda Kahlo, The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xolotl, 1949. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Kahlo’s relationship with fellow painter Diego Rivera was nothing short of volatile. Their marriage swung vertiginously between passion, alienation, and anger. But through it all, both regarded their love as deep and essential. “Your word travels the entirety of space and reaches my cells which are my stars then goes to yours which are my light,” Kahlo wrote in one of many love letters to Diego. This painting unearths the complexity of their relationship, and of Kahlo’s view of love in general. Like an evolutionary drawing or family tree, the Aztec Earth Mother Cihuacoatl holds Kahlo, who holds Rivera in return. The composition emphasizes Kahlo’s independence, but also her frustrating inability to have a child; instead, she seems to suggest, she’s fated to nurture a childish husband.

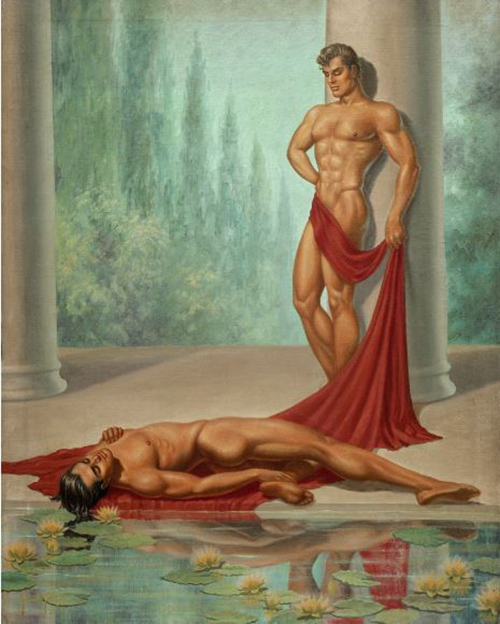

George Quaintance, Idyll, 1952

George Quaintance, Idyll, 1952, TASCHEN

George Quaintance, Idyll, 1952, TASCHEN

Quaintance made his titillating “physique” paintings in an era when homosexuality was widely repressed, and graphic homosexual imagery was downright illegal. So the Arizona-based artist (who had also worked as a Vaudeville dancer and celebrity hair stylist) mischievously skirted oppressive, homophobic legislation by obscuring his chiseled subjects’ cocks with tight-fitting jeans or strategically placed guitars, bits of fabric, and sprays of water. Here, Quaintance borrows a classical colonnade as the backdrop for a tender, come-hither moment between two adonises.

Leonor Fini, Les Baigneuses (The Bathers), 1972

Leonor Fini, Les Baigneuses (The bathers), 1972, Weinstein Gallery

Fini, a leading female Surrealist, was proudly bisexual and an outspoken proponent of polyamory. These convictions emerge regularly in her hazy paintings of powerful women enjoying all manners of pleasure. While she is heralded for being the first woman to paint an erotic male nude, lesbian lovers were her most frequent subject. As in this work, Fini depicts them delicately caressing each others’ skin or gazing at each others’ half-nude bodies.

Nan Goldin, Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City, 1980

Nan Goldin, Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City, 1980,

'Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency' at Museum of Modern Art, New York

This work hails from Goldin’s “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” a mesmerizing and at times devastating series of portraits she took in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. Together, the 700-some photos track the extreme highs and harrowing lows of love and sex as experienced in the New York, Berlin, and Boston countercultures during the Reagan era. Here, Goldin catches her friends Rise and Monty as they hungrily make out, clutching at each others’ hair. The beer can behind them alludes to the drug- and alcohol-fueled trances that often lubricated the heady scenes pictured through Goldin’s lens.

Kerry James Marshall, Slow Dance, 1992–1993

Kerry James Marshall, Slow Dance, 1992-1993

'Kerry James Marshall: Mastry' at MCA Chicago, Chicago

Marshall’s paintings depicting the everyday lives of African-American figures gracefully resist racial stereotyping. This canvas shows two lovers slow-dancing in their living room, surrounded by comforting objects that allude to their pastimes and cultural background—a candle burns from a traditional Haitian bottle and a ballad wafts over the room. While these details are culturally specific, Marshall captures a universally relatable experience: a tender, romantic moment, and the anticipation of moving a relationship to the next step.

Nicole Eisenman, Sloppy Bar Room Kiss, 2011

Nicole Eisenman, Sloppy Bar Room Kiss, 2011

ICA Philadelphia

We’ve all been there—a sloppy, drunken kiss as the bartender announces last call. Eisenman renders the scene with her signature mix of humor and poignancy. The androgynous couple, their nerves lubricated by beer and their heads supported by the wooden table beneath them, are blissfully unaware of the sour-faced, melancholy lot that surround them. This, Eisenman seems to imply, is the beauty and trouble of love: the ease at which we get lost in it.

—Alexxa Gotthardt

CORRECTION:

An earlier version of this article included Malick Sidibé’s photograph Nuit de Noel (1963). However, the pair captured in the photograph are in fact brother and sister, not lovers.

https://

www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-greatest-lovers-art-history