The Violence of the 2017 Whitney Biennial

One of the themes of this year’s Whitney Biennial appears to be violence, and not every artist has the ability to transform it into a successful work of art.

Jordan Wolfson’s “Real Violence” (2017) on display at the 2017 Whitney Biennial

Jordan Wolfson’s “Real Violence” (2017) on display at the 2017 Whitney Biennial (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

All art is political, so I don’t see this year’s Whitney Biennial as any more or less engaged with the terrain of politics than the institution’s previous biennials. What it’s more focused on is hybrid identities, particularly those not represented by the Trump administration or a political party that has gerrymandered its way to minority rule. Curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks have given us an engaging, if uneven, Whitney Biennial. While this event may no longer offer an accurate barometer of that nebulous thing called American art, it does offer an artistic essay about the times.

There’s a real emphasis on representation and notions of truth here, which take on a new urgency at a time when “fake news,” the weaponization of “identity politics,” and nativist xenophobia are on the rise. The abstractions that influence our perceptions of reality are being scrutinized, and rightfully so. But perhaps the most notable theme of the exhibition is violence — its portrayal and circulation, and the systems of oppression that support it. Unfortunately, the biennial fails to probe violence in international theaters of war, prioritizing the way it’s acted out within US borders; that is only one aspect of a much larger story.

I would suggest that at the core of the biennial’s take on the depiction of violence are four works that explore the topic in their own way: Jordan Wolfson’s “Real Violence” (2017), which quickly became a conversation piece; Dana Schutz’s “Open Casket” (2016), which is already a focus of protests; Henry Taylor’s “THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!” (2017), which looks at the shooting of Philando Castile, livestreamed by his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, on Facebook; and Postcommodity’s “A Very Long Line” (2016), which is part of a broader focus by the three-person collective on the violence of borders and colonialism.

After the initial shock of watching a white man bash in what appears to be another white man’s head on a contemporary Western street, Wolfson’s VR work feels surprisingly hollow, supplementing the stereotype of a white male interest in violence bred by ennui. The fact that both figures are white is not incidental — it points to Wolfson’s fixation on whiteness in his continuing work about violence. Artist Ajay Kurian (who’s also included in the biennial) wrote about Wolfson’s “Colored Figure” (2016) last year, identifying a “breed of white males who believe they are persecuted while being the aggressor, and are powerful while maintaining a sense of painful fragility” as one of the overarching themes in the US today. Here, like in Wolfson’s previous work, the white body is on display, but the larger question is whether it functions to universalize the scene or mar it in a feedback loop, providing us with a GIF of violence that feels difficult to escape once we’re confronted with it.

The aestheticization that takes place in “Real Violence” is deeply disturbing. Wolfson seems to be trying to transfer the ultra-violence of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) or David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) — or even Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible (2002) — to VR, but he contributes little to the conversation; all those movies tackled the topic with far more sophistication and, frankly, gore. This is violence reduced to a formal concern, as if the context could ever be removed. The fact that Wolfson tries to couch it in a Jewish tradition, playing a Hebrew prayer over the scene, is equally off-putting. It shows a removal from the threat, violence abstracted into an idea.

The perceived — not actual — threat of random violence is at the core of white supremacy, and it’s often used as a justification for continuing violence against non-white populations. We have seen this at work recently with President Trump’s executive order announcing the publication of a weekly blotter of crimes committed by immigrants (aka “removable aliens”): the perceived threat of terrorism becomes an excuse for further violence against those who are often fleeing it. The feedback loop distorts our perception.

Yet violence is real for many of us, not an abstraction. Western imperialism and white supremacy destroy whole cities, push millions of refugees into desperate conditions, criminalize entire populations, and mine resources — human and otherwise — for their own benefit. To say that Wolfson’s position is detached from the ecosystem of violence is an understatement; it evokes the puerile outbursts of gamergate trolls, removed from the conditions of the real world and paralyzing the viewer with a threat they’re powerless to control. Dana Schutz’s “Open Casket” (2016) suffers from similar problems, but it also reveals the inability for most painting to render pain and history.

Dana Schutz’s “Open Casket” (2016) (photo by Benjamin Sutton for Hyperallergic)

In 1955, Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi after being falsely accused of flirting with a white woman. He was only 14. His mother, Mamie Till Bradley, insisted on having an open-casket funeral, and the graphic photographs of his body that were printed in the media are credited with helping to catalyze the civil rights movement. Schutz’s painting is based on one of them. What she couldn’t have foreseen while making it is that last month, the now 82-year-old woman responsible for the accusation, Carolyn Bryant Donham, would finally admit that she’d fabricated the story that killed Till. That fact adds another troubling layer to Schutz’s painting.

The portrayal of violence, and particularly this type of extreme disfigurement of a victim, is difficult to look at, and the artist’s choice to paint it is particularly strange. The image is particularly troubling because a white woman’s fictions caused the murder of the young man, and now a white female artist has mined a photograph of his death for ostensible commentary, which in reality does little to illuminate much of anything. What is Schutz contributing to the imagery or story of Till, or to the rendering of violence? The position of the contemporary artist is one of precarious privilege, but here the artist appears to have absolved herself by refusing to implicate herself in the image, preferring to let the history of the image, and her painterly additions, make the case for her. Removed from culpability, she has instead used Till’s brutalized likeness as a way to explore painterly technique, and without consulting the title, most people would likely not even recognize the subject. What does this do? How does the subject work here? How is this not a form of exploitation?

It’s notable that another of Schutz’s paintings, “Fight in an Elevator” (2016), renders an altercation between two African-American celebrities, Jay Z and his sister-in-law, Solange Knowles, as a jumble of forms. The Whitney Biennial catalogue reproduces “Fight in an Elevator” and cites the actual subject of the painting, but at the museum we see a different work from the same series, the monumental “Elevator” (2017), in which Schutz renders piles of body parts in oil on canvas. The white artist again gives us a fragmented portrayal, breaking bodies apart, removing their features, and rearranging them at will in a formal way. Her failure in adding any insight or to seeing why this might be offensive is the essence of that popular artspeak term, “problematic.”

Henry Taylor’s “THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!” (2017)

(photo by Benjamin Sutton for Hyperallergic)

Unlike Schutz’s “Open Casket,” Henry Taylor’s painting about violence against African Americans, this time by the police, is less gratuitous and more successful. It starts by giving us a straightforward and identifiable view of the infamous scene in a car that was livestreamed to thousands of people online.

In Taylor’s painting, Philando Castile slouches in his seat as officer Jeronimo Yanez points a gun at him. The perpetrator’s arm is lightened, while the victim’s eyes look upwards and his wound is removed, replaced by splashes of yellow and black paint. This gesture emphasizes the fiction of the painting itself and reflects a self-conscious understanding that the artist’s image can never compare to the original. How can you compete with something as raw and immediate as that livestream? Here, the artist does his part by tending to the wound in the best way he knows how.

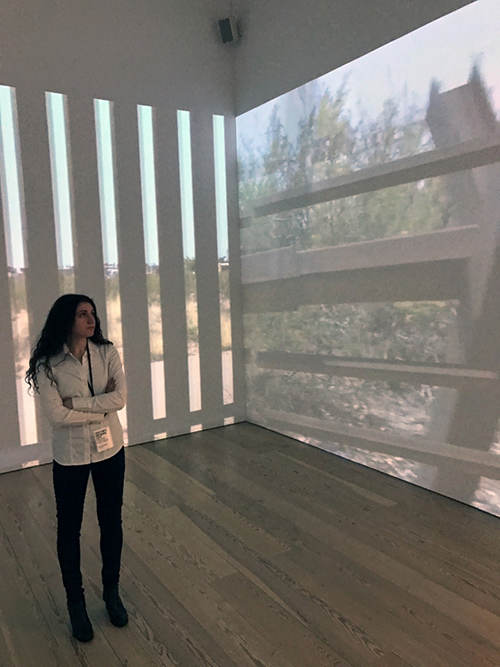

Inside the room that displays Postcommodity’s “A Very Long Line” (2016)

What’s more, by freezing a moment of the raw footage, Taylor is able to plug the incident into a larger system of violence. He highlights the importance of it happening in a car, that great symbol of what some would describe as American freedom. Here, any sense of safety in the vehicle is destroyed by faceless state violence, which reaches in to kill. We’re given the perspective of Diamond Reynolds, but it’s clear that the man with the gun is oblivious — or apathetic — to the viewer’s presence. But even here the tendency to stereotype slightly calcifies the composition, offering us insight at arms length.

That distancing is more pronounced in the immersive four-channel video by Postcommodity, which envisions the border between the US and Mexico as an enclosure or sorts. The violence of state-sponsored division, which has cut through indigenous lands, severed once unified communities of color, and been bolstered by dangerous nationalistic rhetoric, is shown as a continuous horizon pan. Fences obscure our view, and we’re left wondering whether we’re standing on the inside or outside — what side of the border do we naturally associate with? The fragmentation is smartly devised to disorient us. The border, which is often portrayed as a fixed, physical site, becomes more psychological, leaving us frustrated by the fact that there’s no way around or through it.

Aliza Nisenbaum’s “La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times” (2016)

(all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

In addition to these four works that portrayal violence in different ways, I would add Aliza Nisenbaum’s “La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times” (2016) since it doesn’t directly portray violence but inserts it as a ghostly presence through the pages of the New York Times. Nisenbaum’s painting, maybe inadvertently, captures the distance readers (or viewers) face in regards to their subject. It is a welcome commentary on our desire to create meaning in the everyday. The intimacy of the two figures overwhelms any looming danger contained on the pages. She treats the news as a casual undertaking, part of a personal ritual, half distracted and somewhat choreographed for those around us.

Despite the different ways they succeed and fail, all of these images raise one consistent question: who is being held responsible for the violence they depict? And, I would add, how do we start fixing that?

We can’t pretend that images of violence don’t have an impact on a very personal level. We can’t close our eyes to the cycles of pain that these systems continue to feed on. The challenge of today is to engage with images that we find difficult, painful, and complicated. Artists can imagine the world any way they want, but we also have a responsibility as viewers, critics, patrons, and others to respond, take action, and challenge them when they reveal something that we find particularly troubling. Often art mines our collective consciousness to demonstrate a truth, other times it reveals a breakdown in a system that refuses to mend its wounds or recognize new perspectives. Museums are no longer the rarefied sites that demand we listen. Sometimes we must talk back. Maybe this is one way to begin:

https://hyperallergic.com/366688/the-violence-of-the-2017-whitney-biennial/