L.A. Reincarnation: New Art Spaces in Vintage Settings

The eastern facade of the Marciano Art Foundation, part of a former Masonic temple from 1961, with an exterior mural by Millard Sheets. Credit Emily Berl for The New York Times

LOS ANGELES — It’s hard to know what to make of the bright gold stripes running down the dark travertine lobby walls of the Scottish Rite Masonic Temple here. From a distance, they look like long strands of jewelry. Up close, they resemble chains of hieroglyphics. But how to crack this code, nobody knows.

The pattern, made of gold-glazed ceramic tiles, is just one of the beautiful and inscrutable details of the 1961 building, newly visible as the permanent showplace of the contemporary art collection owned by the brothers Maurice and Paul Marciano, co-founders of the Guess empire. After much anticipation, the Marciano Art Foundation opens to the public on Thursday, May 25, with free admission, though reservations are required.

The California artist-architect Millard Sheets designed the imposing edifice on Wilshire Boulevard for the Masonic brotherhood (a fraternal society with roots in medieval builders’ guilds), planting his own symbolic murals and mosaics throughout. The Marciano Art Foundation bought it in 2013 for $8 million.

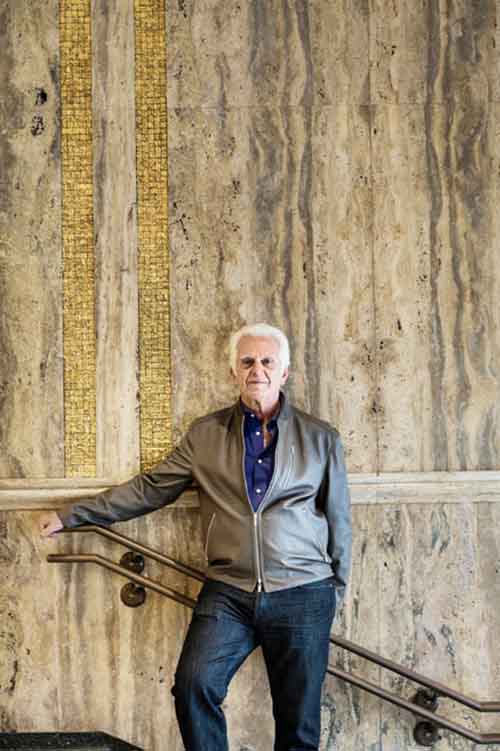

“When you find something this beautiful, you want to preserve and restore it,” said Maurice Marciano, 68, who in retirement has been overseeing the building’s transformation and conservation while his younger brother Paul remains an executive at Guess.

Maurice Marciano, a co-founder of Guess, at the Marciano Art Foundation, in front of its travertine lobby walls lined with golden ceramic tiles. Credit Emily Berl for The New York Times

“It’s been interesting for us to turn something very secretive and formidable into something friendly and curiosity-driven,” added Kulapat Yantrasast, the project architect. “It’s especially interesting for L.A., because we tend to love what’s new and shiny instead of investigating history in this way.”

The Marciano Art Foundation is not alone in going the historical route. Several new arts institutions in development that will expand the city’s museum landscape have opted to reimagine existing buildings rather than build sleek new ones, as the Broad museum did in 2015 with its Diller Scofidio + Renfro design.

Continue reading the main story

RELATED COVERAGE

Is This Los Angeles’s $600 Million Man? JAN. 18, 2017

Mr. Yantrasast’s firm, WHY, is also adapting a 1950s warehouse downtown for the Institute of Contemporary Art L.A., a reincarnation of the Santa Monica Museum of Art set to open in September. Also downtown, the real estate developer Tom Gilmore and the arts leader Allison Agsten have teamed up to open the Main Museum in a 1905 Classical Revival bank building, with an adjacent storefront space already in use for exhibitions, and plans to open the bank vaults for performances and projects in 2018.

A new Alex Israel mural visible from the lobby of Marciano Art Foundation, with restored chandeliers designed by Millard Sheets. Credit Emily Berl for The New York Times

And on the Hollywood front, the architect Renzo Piano is transforming the 1939 May Company Building department store on Wilshire — a leading example of Streamline Moderne — into a museum for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, designed to showcase film posters, photographs, drawings and other memorabilia, from Dorothy’s red slippers to a spacecraft model from “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

As contemporary art has grown in its scale and ambitions, the trend of converting industrial spaces to provide cheap and flexible space has also taken off.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, where Mr. Marciano is co-chair of the board, helped lead the way in the early 1980s by turning a warehouse, now known as the Geffen, into a still-raw-seeming exhibition hall. Mass MoCA, in former textile mills of North Adams, Mass., and Dia:Beacon, in a defunct Nabisco box factory in Beacon, N.Y., followed.

And European cities where space is scarce have long proven resourceful, transforming train stations (Musée D’Orsay in Paris and Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin) and power plants (the Tate Modern in London and the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology in Lisbon) into visual arts centers. In 2015, after years of trying out different spaces, the Prada Foundation established a permanent home in Milan in a former gin distillery.

So far, the cultural citadels of Los Angeles, a city still in its infancy by comparison, have mainly taken the form of gleaming new edifices like the Getty Center in Brentwood and the Broad, with Peter Zumthor’s proposed addition to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in development.

But other museum leaders here call adaptive reuse inspiring and practical. “With so many wonderful vacant buildings downtown, there is no need for a museum like ours to begin building from scratch,” said Elsa Longhauser, director of the Institute of Contemporary Art L.A.

The obvious incentive is financial. While structural changes to meet earthquake codes can throw an expensive wrench into the works, museums can get a better price per square foot by adapting an existing building if its bones are good.

“In a perfect world, you would save a little money this way,” said Mr. Gilmore, the developer behind the Main Museum. “But the case I make is that even if it costs the same, you’re coming out ahead on the sustainability end for recycling materials and not tearing down a building.” Mr. Gilmore credits the resurgence of downtown Los Angeles in large part to a 1999 city ordinance facilitating the conversion of office buildings into apartments.

Then there are the branding possibilities. If the convention for world-class museums is to have a custom-built home, preferably by a Pritzker-winning “starchitect” (“museum buildings as logos” as Mr. Yantrasast sees it), some smaller institutions prefer to use existing spaces — the funkier, the better — to convey their own sense of adventurousness.

Allison Agsten, the director of the Main Museum, seated on artwork by Alice Könitz.

Credit Emily Berl for The New York Times

As Ms. Agsten of the Main Museum, a noncollecting institution, pointed out: “This is definitely not the kind of place you would want to hang your Rothkos. A space like ours sets the visitor up for a different kind of experience — for a sense of experimentation.” She noted that artists had already expressed interest in using the Main’s bank vaults, hinting at another motivation behind the trend: a growing weariness among artists over showing work in predictable, and interchangeable, art fair booths and even pristine gallery rooms.

“Most artists would rather see work installed in a rough space than in gleaming new exhibition halls because it’s what their studios look like — a continuity between place of production and place of presentation,” Mr. Yantrasast said.

Jim Shaw, a Los Angeles artist, is creating a special exhibition for the opening of the Marciano Art Foundation in a vast, raw ground-floor space that used to hold a 2,400-seat theater. A conspiracy-driven, apocalyptic-sounding excavation of power structures called “The Wig Museum,” his dense installation includes wigs and enormous theatrical backdrops left over from this the Masons, who staged their own plays as initiation and education rites.

Having worked in museum conversions before — he recalled a former slaughterhouse, Les Abbatoirs, in Toulouse, France — Mr. Shaw said these adapted spaces have a big advantage: “When you’re an artist, it’s terrible to have a blank page. It’s better to have something to work off of, riff off of, a starting point.” The disadvantages, he said, are mainly practical: “I could use more electrical outlets now.”

Throughout the Masonic Temple, which is not a landmark building, Mr. Yantrasast worked to preserve some original elements while also creating clean, light-filled spaces to show off the ultracontemporary art that the Marcianos have acquired, often together, over the last two decades: an on-trend collection that is rich with Los Angeles artists such as Mark Grotjahn, Jonas Wood, Analia Saban and Oscar Tuazon. (The inaugural selection was organized by a guest curator, Philipp Kaiser.)

Jonas Wood paintings in one of the upstairs galleries. Credit Emily Berl for The New York Times

The Marcianos financed the conservation of three murals by Millard Sheets while working with his estate to relocate others; repaired the gold detailing in the lobby walls as needed; and preserved almost all elements on the facade, including sculptures of celebrated Masons like George Washington. They also turned a small Masonic library into an anthropological museum, with literature but also costumes and hats left on the site. “It’s the museum of the museum,” Mr. Marciano said.

The contemporary art gets the most play on the third floor, formerly a Masonic banquet hall large enough to seat 1,500 members (all men). Mr. Yantrasast removed the low ceiling to expose the gable roof and create a soaring space. He also carved out three smaller galleries to the west, each of which currently pairs two heavyweight artists: Mike Kelley and Sterling Ruby, for starters.

But there are moments when the new art and historical building have competing agendas. Walk east on the third floor, and you find a panoramic Sheets mosaic mural from 1961 with a nature theme, complete with stylized roosters and glittering trees.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to get a full view of the mural: A new wall has been built parallel to it, just six feet in front.

Mr. Marciano called the Sheets mural “beautiful and powerful,” a personal favorite. But he explained that he had the wall erected to keep the building’s history at a remove. He didn’t want the mural to eclipse his contemporary art: “The mosaic is too commanding,” he said. “It would have completely overtaken the view.”

Correction: May 19, 2017

An earlier version of this article described incorrectly the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. It is a series of degrees that are awarded by Masonic groups; it is not the Scottish branch of the Masons.