정준모

Auguste Rodin’s Gates of Hell cast in bronze by Alexis Rudier, (1917). Courtesy of Museé Rodin.

Rodin Casts a Long Shadow

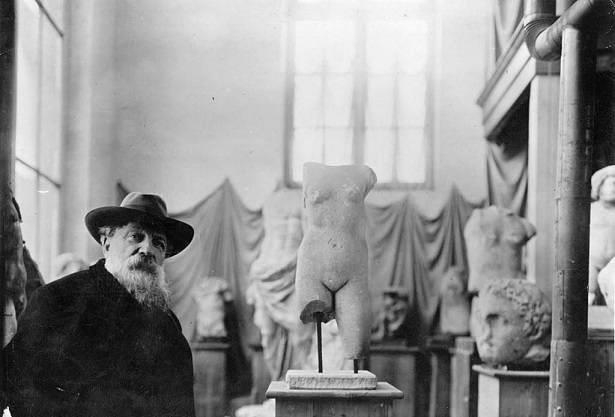

Rodin is not the first artist to frustrate our conventional definitions of an original work. As the Musée Rodin notes in its online education material, “Starting in the Renaissance, sculptors only do the modeling; the work in plaster, bronze, or marble is produced by casters or carvers.” Later, in the 17th century, under Louis XIV, sculptors including Antoine Coysevox and François Girardon were already supervising large staffs and armies of many assistants of every variety.

Rodin’s approach influenced an entire generation of artists that followed. As Catherine Chevillot, who organized the Grand Palais exhibition, wrote in the catalogue: “At the beginning of the 20th century, all the young sculptors, including Brancusi, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and Picasso, do, in fact, go through a Rodinian phase.”

Rodin’s influence continues into the Modern era. As the sculptor Antony Gormley writes in the catalogue for Rodin’s Grand Palais exhibition, the sculptor’s greatness “lies in a paradox: on the one hand, he embodies the public narrative statuary prevalent in the late nineteenth century; on the other hand, where multiplication, industrial production, the serial repetition of ways of associating one object with another, and his capacity of taking a body apart to then recreate it are concerned, he prefigures Carl Andre and Donald Judd.”

From the Unique to the Multiple Original

Rodin also prefigured contemporary practice—and upended our notion of the original—with his use of the multiple.

The precedent for multiples dates to the 1850s, when artists like Antoine-Louis Barye or Emmanuel Frémiet began to sell a kind of patent for design objects. Foundries such as Barbedienne in Paris produced decorative elements of all sizes, which is how the same candelabra could end up on bridges and fountains from Clermont-Ferrand all the way to Buenos Aires. It is in France that this kind of democratizing art was invented.

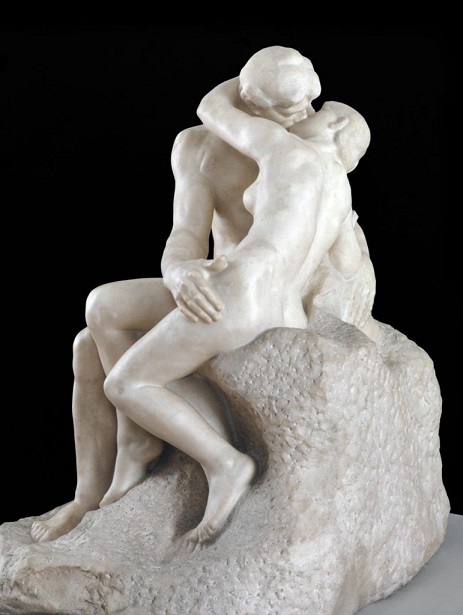

Not long after multiples were popularized in the design field, Rodin began creating multiple casts of his works, starting with She Who Was the Helmet Maker’s Once-Beautiful Wife in 1889. Such casts are usually fabricated from a mold while the artist is alive but can be made posthumously as well.

The (sometimes mistaken) idea that a work made during the artist’s lifetime was produced under his supervision has historically justified a difference in value between lifetime and posthumous works. In fact, the artist did not always oversee production closely, and the artist’s estate must adhere to much stricter rules governing the quality of production than the artist himself did. As attitudes change, this market inequality may come to an end. Indeed, some artists, such as Giacometti, have recently seen an increase in prices for posthumous works. The artists’ beneficiaries may profit from this shift—but so does the public at large, which gains a fuller understanding of the value of the artist’s work.

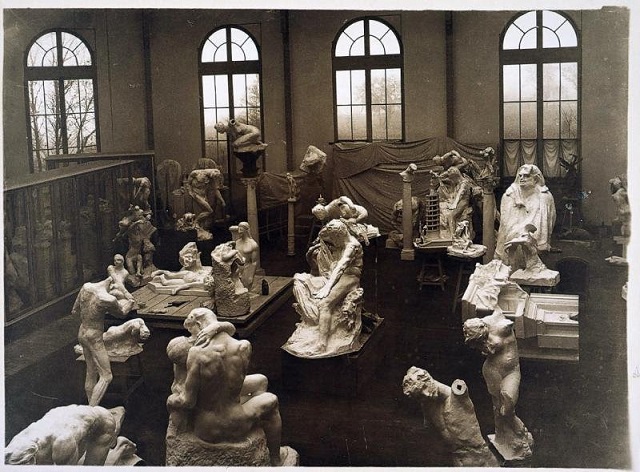

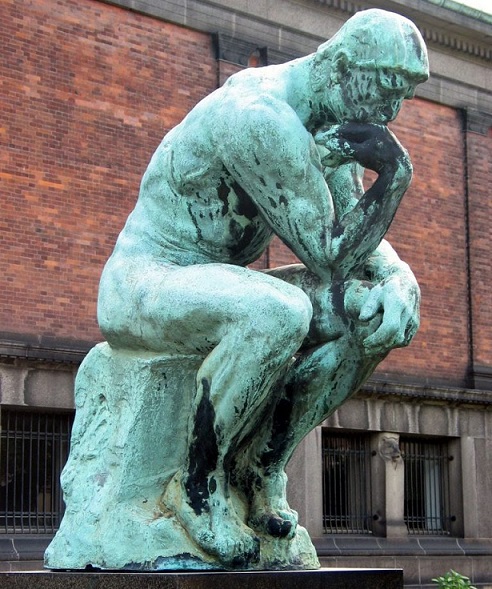

Castings by Rodin displayed in his studio, Meudon. At left, The Kiss (1901–1904); third left, a casting of French writer Honore de Balzac. Photo by Pierre Andrieu/AFP/Getty Images.

12 Copies—the Limit of the Original Work?

When production occurs on various timelines, how can we distinguish between the original and its reproduction? In France, the law (particularly in terms of customs or tax regulations) provides some elements of an answer—although the relevant text is rather obscure, cryptic, or merely an article in a provision to the general tax code concerned with the application of reduced VAT rates. In this context, the term “original work of art” encompasses “the casts of sculptures in drawings limited to eight copies and under the control of the artist or his beneficiaries.”

Under French law, the maximum number of casts allowed for copies to qualify as “multiple originals” is 12. (It is commonly permitted to add to the eight copies another four artist proofs.)

The origins of this figure stretch back to the beginning of the 20th century, when the first limited editions entered the market courtesy of French designers. At the time, the sales price of a work in bronze was about three times the cost of its production. Eight copies were drawn for the dealer (numbered 1/8 to 8/8) and four additional for the artist, which served as payment in kind to the sculptor (these épreuves d’artiste are numbered differently, from E. A. I/IV to E.A. IV/IV).

From France, this number has made its way around the world and has entered, for example, American legislation to serve as the basis for defining multiple originals.

In a 2012 decision, the French Cour de Cassation, aware of the as yet undefined nature of these multiple copies, elaborated further on the definition of original works to note that they must be drawn from the plaster or terracotta model produced personally by the artist; in its execution, “these material supports of the work bear the mark of their author’s personality and are thereby distinct from a simple reproduction.”

Americans deal with such problems more pragmatically. Instead of anchoring descriptions on a qualifier as original, the essential thing for United States law is ensuring public awareness of an object’s characteristics, whether it is a multiple, produced during the artist’s lifetime or after their death, the name of the caster and the precise number of copies. For, in the end, what is important in law is that no one is deceived and everyone can form a subjective opinion based on objective facts.

Rendering of Jeff Koons’s Bouquet of Tulips (2017). Courtesy of Noirmontartproduction.

Contemporary Ties

Rodin’s novel approach to the original enables us to draw a direct line between the French artist and major contemporary artists today. Jeff Koons, for example, maintains and extends this tradition of a communal artisanal studio practice. In an article by Béatrice De Rochebouet published in Le Figaro in 2014, Koons’ studio is described as a place where “a veritable army of more than a hundred people contemplates materials, ranging from wood via stainless steel to ceramics, with an elite group of physicists and technicians.”

Just this year, Koons offered a monumental work, Bouquet of Tulips, as a gift to the city of Paris. Created from polychrome bronze and steel, the sculpture stands at more than 38 feet and weighs more than 72,000 pounds. It was produced in a German factory under the watchful eyes of an agent of the artist and, barring further delays, is expected to be installed later this year. It is noted as an original work and is accepted by the Paris authorities as such.

Koons is one of many contemporary artists who push Rodin’s approach to its logical conclusion, using machines and studio assistants to realize his vision. He is, in a certain way, the ultimate symbol of the distinction between creation and production.

French sculptor Francois Auguste Rene Rodin (1840–1917) in his museum at Meudon. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

The Romantic Approach to Art and Law

Nevertheless, despite the wide recognition for artists like Koons, many still hold onto erroneous conceptions that only works that come straight from an artist’s hands can be deemed original. We are willing to tolerate that multiples are produced, but, even then, we seek to be reassured by tracing the artist’s touch back through the complex molding process.

What complaints we hear when posthumous casts are produced, while artists such as Rodin never cast even the smallest bronze themselves! Do people seriously think that Giacometti or Brancusi created their bronzes in the heat of their own fireplaces? Are people aware that all of the Degas bronzes in the Musée d’Orsay were cast after the artist’s death? The case of Brancusi is all the more significant as the Rumanian sculptor was, in 1907, Rodin’s student and could not but have learned the rules of the great master’s artistic production.

What will people say when, in the near future, an artist sends an electronic file from New York to Hong Kong, where a 3-D printer produces a sculpture that the artist never laid hands, or even eyes, upon? As Rodin reminds us, what really counts is the mind, not the hand.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari