Participating artists came to the defense of the financially strapped quinquennial.

News of documenta’s precarious financial situation came to light last week when the German newspaper HNA reported that the event’s joint owners, the city of Kassel and the state of Hesse, agreed to issue an emergency support package of €7 million ($8.3 million) to keep the exhibition up and running after the latest iteration, which closed yesterday, went drastically over budget.

In the letter, the artists criticized the “ancient financial warfare technique” of “shaming through debt,” explaining that “these terms of assessment have nothing to do with what the curators have made possible, and what the artists have actually done within this exhibition.”

The signatories represent the vast majority of the more than 250 artists who participated in documenta 14. Additional artists “continue to request [to have] their names added as word gets out,” according to an emailed statement accompanying the letter. The signatories suggested that the HNAarticle was an attempt “to politically subjugate” Szymczyk, documenta CEO Annette Kulenkampff, and other officials.

In their letter, the artists praised documenta 14’s decision to organize sprawling presentations in both Kassel and Athens, although HNA suggested that the Athens branch of the show was the primary reason for the overspending. “We applaud the decision by documenta 14 to not charge ticket prices in Athens,” the artists wrote. “In fact, more such moves of dislocation from comfort zones, and inclusion of multiplicity of voices, many standing outside of western hegemony, should be the future.”

The artists also reiterated the curatorial team’s assertion that the significance of art—and the success of an exhibition—cannot be measured by its financial return. “We are concerned about this urge to put ticket sales above art… We feel that casting a false shadow of criticism and scandal over documenta 14 does a disservice to the work that the artistic director and his team have put into this exhibition.”

The signatories praised documenta for its continued support of artists, especially those “not represented by commercial galleries,” those working “in non-material, ephemeral, and social practice,” and artists from parts of the world “still underrepresented in major art events.”

Not all exhibiting artists agreed with the letter, however. In a response posted on publishing platform e-flux, artist Georgia Sagri wrote that she didn’t understand “what this letter brings from the side of the artists” and questioned why the exhibiting artists should take responsibility to “save documenta as an institution” and “restore the reputation of its current curators.”

Although Sagri said she doesn’t regret participating in documenta 14, the demands of the project and the sensitivities surrounding the show did take their toll. “I lost friends and I didn’t make any new ones through this exhibition and that will take time to be restored,” Sagri wrote. “I didn’t make any money out of this exhibition and my life wasn’t improved.”

To read the artists’ letter in full and view the list of signatories, see below.

We the undersigned artists, writers, musicians, and researchers who participated in various chapters of the current documenta 14—Exhibition, Parliament of Bodies, South as a State of Mind, Listening Space, Keimena, Studio 14, An Education, EMST collection, and Every Time A Ear di Soun—wish to share some thoughts about the possibilities and potential of documenta. Firstly, we acknowledge those participants in documenta 14 whom we have not been able to reach at the time of writing, those with whom we could not get to consensus, those participants no longer living, and especially those who passed away while participating in documenta 14. We write this in the context of the invitation of “Learning from Athens,” and the idea of first unlearning the familiar. We also take note of documenta’s specific history as a response to the evil of the Second World War and the Holocaust. We see that initial, painful legacy evolving toward an imaginative and discursive space that can contribute toward challenging war capitalism, unjust borders, and ecological suicide.

The initial iterations of documenta rose in the shadow of rebuilding, after a World War that caused Adorno to disavow a future for poetry. From the 1990s, the exhibition joined a global turn toward decentering the Western art-historical canon, by beginning to emancipate institutions, venues, and universities. There was a welcome, and overdue, acceleration of the presence of artists, theorists, and thinkers from the Global South, starting from documenta 10 (Catherine David), continuing through documenta 11 (Okwui Enwezor), documenta 12 (Roger Buergel / Ruth Noack), and documenta 13 (Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev). documenta also began a spatial decentering, initiated by documenta 11 with platforms in Berlin, Vienna, New Delhi, St. Lucia, and Lagos. This was followed by documenta 12 magazine, a network of 100 magazines world-wide, and documenta 13, with satellite projects in Kabul, Alexandria, and Banff. It is in line with documenta’s long heritage of decentering, and decolonizing, that we welcomed the decision to launch documenta 14 as a dialogue between Athens and Kassel.

documenta 14’s Athens chapter began a full two years before the official opening, with the launch of the South as a State of Mind journal in 2015, the weekly public program Parliament of Bodies in 2016, and finally, the opening of documenta 14 | Athens in April 2017, two months before Kassel. documenta 14’s curatorial team worked to encourage autonomous spaces, free of authoritative statements or frameworks. However, criticism appeared immediately, focusing on budget and infrastructure, with far less attention paid to the artworks, journal, radio, public TV, live music, education, and public programs. A few critics did raise some points that were also being debated among the artists and curators. One of those centered on the challenges of working with local communities in an environment of equality and partnership, while working within large exhibition infrastructures. Another question was whether large exhibitions are the best venue for breaking down discursive hegemonies. documenta 14 had a shared commitment to preserving the autonomy of local spaces and communities, and conducting conversations around culture within a dynamic of mutual exchange, respect, and curiosity.

Recently, criticisms of documenta 14 have been expanded to suggest that a deficit in the operating budget is primarily due to the Athenian chapter of documenta. We are concerned about this urge to put ticket sales above art, and we believe that Arnold Bode would have rejected this as distorting the purpose for which he gifted documenta to Kassel. We applaud the decision by documenta 14 to not charge ticket prices in Athens. We should also consider the responsibility to address the economic war fought by European institutions against the Greek population, during the recent debt crisis. We feel that casting a false shadow of criticism and scandal over documenta 14 does a disservice to the work that the artistic director and his team have put into this exhibition. Shaming through debt is an ancient financial warfare technique; these terms of assessment have nothing to do with what the curators have made possible, and what the artists have actually done within this exhibition.

What should be highlighted are the positive impacts of exchanges within documenta, including the decentering that occurred through the exhibition.This has caused a creative friction that is an active dialogue between citizens, communities, and institutions of Athens, Kassel, and the rest of the world. This is only a first step, and conversation must continue in coming years. In fact, more such moves of dislocation from comfort zones, and inclusion of multiplicity of voices, many standing outside of western hegemony, should be the future. What we do not need is a neoliberal logic, as well as its institutional critique, that does not allow the possibility of alternative methods, stories, and experiences.

One aspect that makes documenta remarkable is its support of large numbers of artists who are not represented by commercial galleries, and in fact work in non-material, ephemeral, and social practices. Many come from regions and countries still underrepresented in major art events. Naturally, many of the works produced here very consciously suggested proposals for equality and solidarity. We understood this exhibition to be a listening documenta. The curatorial team took care to listen closely and carefully to artists, rather than imposing a top-down curatorial will. The exhibition tried to be inclusive, as well as specific, emphasizing people and stories from the so-called periphery, and voices belonging to those who have faced, and overcome, hardship. Whether in crisis or inflection point, enquiry was encouraged, challenging the more frequent move of wanting to own other peoples’ understanding. The curatorial innovation was to create the space for such an encounter, in Athens and Kassel.

There are many interventions, by the artistic director and curatorial team, which brought together new configurations and dialogue between generations of artists, much of which is invisible to the critics. Also crucial has been the displaying of rare historic material, some of it centuries old and from all parts of the world, some of which has never been displayed in a museum. By commissioning new work in dialogue with centuries-old heritage, new alliances were created across territories and times. The juxtaposition of stories from all over the globe can be disorienting, but that is precisely the point of the structure of this exhibition. Large gestures have to be measured alongside hundreds of small ones to make a complex whole, all going towards globalizing the art historical canon. The challenge for all of us—artists, critics, and audiences—has been to experience that complexity, while subjected to practical economic constraints. We need to think of more economically egalitarian ways of viewing a large exhibition, while resisting the dominant narrative that is singularity (“the Athens model”) over complexity (what actually happened in Athens and Kassel).

documenta was founded as a brave response to a dark history. The 1933 Nazi regime received support from Nuremberg and Kassel, because of the presence of the arms industries. On February 11, 1933, eleven days after taking power, Hitler spoke at the Friedrichsplatz in Kassel. On November 7, 1938, two days before Kristallnacht in other German cities began, Kassel and surrounding villages saw anti-Jewish pogroms. In archival footage of trains carrying people to concentration camps, the insignia “Deutsche Reichsbahn Kassel” is visible on some carriages. After 1945, in order to erase this Nazi legacy, Nuremberg hosted war crimes trials, and, ten years later, Kassel hosted the first documenta. Kassel’s central Friedrichsplatz was bifurcated, so that no spatial trace of the 1933 rally remains. In light of this unique founding history, documenta’s unique mission has always been, and must continue to be, encouraging conversations in the contemporary arts that can oppose the spectres of nationalism, neo-nazism, and fascism that are still haunting the planet.

The world has transformed many times over since 1955. Western Europe is no longer the center of contemporary exhibition making. It is being challenged to take its place as one among equals, as Asia, Latin America, Africa, Middle East, Southern and Eastern Europe come forward to claim their presence. The current documenta continues the arc of the previous four documentas, by highlighting the edges of Europe, the voices of Global South realities, and the presences that press against heteronormativity. Receiving the world, as equals, contrary to anxieties, also contributes to radiance. The contemporary arts no longer looks toward a European exhibition to lead the way in ideas about what art can do, and what it should do. However, Kassel does exercise influence in contemporary art discussions that are emerging from many locations (Bamako, Beirut, Bucharest, Cairo, Dakar, Gwangju, Havana, Istanbul, Jakarta, Johannesburg, Kochi, Ljubljana, Mexico City, Moscow, New Orleans, Sao Paulo, Shanghai, Sharjah, Warsaw, Zagreb, and numerous others). We ask the documenta supervisory board to vigorously defend the curatorial team’s vision of documenta 14, and future curatorial teams to continue to make exhibitions that are accessible to all, and that decenter art history, challenge war and nationalism, and fight against the poisoning of the planet.

Signed,

1) Aboubakar Fofana

2) Achim Lengerer

3) Agnes Denes

4) Ahlam Shibli

5) Aki Onda

6) Akio Suzuki

7) Akinbode Akinbiyi

8) Alessandra Pomarico

9) Alexandra Bachzetsis

10) Alvin Lucier

11) Amar Kanwar

12) Amelia Jones

13) Anca Daučíková

14) Andreas Angelidakis

15) Andreas Kasapis

16) Andrew Feinstein

17) Andrius Arutiunian

18) Angela Dimitrakaki

19) Angela Melitopoulos

20) Angelo Plessas

21) Angela Ricci Lucchi

22) Anna Papaeti

23) Anna Sorokovaya

24) Annie Vigier

25) Annie Sprinkle

26) Anthony Burr

27) Anton Lars

28) Antonio Negri

29) Antonio Vega Macotela

30) Apostolos Georgiou

31) Arin Rungjang

32) Artur Zmijewski

33) Ashley Hans Scheirl

34) Athena Katsanevaki

35) Banu Cennetoglu

36) Ben Russell

37) Beth Stephens

38) Bonita Ely

39) Boris Baltschun

40) Boris Buden

41) Bouchra Khalili

42) Brett Neilson

43) Cana Bilir-Meier

44) Cecilia Vicuna

45) Christina Kubisch

46) Christos Chondropoulos

47) Click Ngwere

48) Colin Dayan

49) Conrad Steinmann

50) Constantinos Hadzinikolaou

51) Dan Peterman

52) Daniel Garcia Andújar

53) Daniel Knorr

54) David Harding

55) David Lamelas

56) David Schutter

57) David Scott

58) Debbie Valencia

59) Denise Ferreira da Silva

60) Dimitris Papanikolaou

61) Dimitris Parsanoglou

62) Dmitry Vilensky (Chto Delat)

63) Edi Hila

64) EJ McKeon

65) Elisabeth Lebovici

66) Elle Marja Eira

67) Emanuele Braga

68) Emeka Ogboh

69) Emily Jacir

70) Eric Alliez

71) Eva Stefani

72) Evelyn Wangui Gichuhi

73) Feben Amara

74) Franck Apertet

75) Franco “Bifo” Berardi

76) Ganesh Haloi

77) Gauri Gill

78) Geeta Kapur

79) Gert Platner

80) Geta Bratescu

81) Gordon Hookey

82) Guillermo Galindo

83) Guillermo Gomez-Pena

84) Hans D) Christ

85) Hans Eijkelboom

86) Hans Haacke

87) Hiwa K

88) Ibrahim Mahama

89) Ibrahim Quraishi

90) Irena Haiduk

91) Iris Dressler

92) Itziar González Virós

93) Jack Halberstam

94) Jan St) Werner

95) Jakob Ullmann

96) Jess Ballinger-Gómez

97) Joana Hadjithomas

98) Joar Nango

99) Johan Grimonprez

100) Jonas Broberg

101) Jonas Mekas

102) Josef Schreiner

103) Joulia Strauss

104) Katalin Ladik

105) Kettly Noël

106) Lala Meredith-Vula

107) Lassana Igo Diarra

108) Lenio Kaklea

109) Lois Weinberger

110) Lucien Castaing-Taylor

111) Lukas Rickli (Kukuruz Quartet)

112) Macarena Gomez-Barris

113) Magali Arriola

114) Manthia Diawara

115) Maret Anne

116) Maria Eichhorn

117) Maria Hassabi

118) Maria Iorio

119) Marianna Maruyama

120) Marie Cool and Fabio Balducci

121) Marina Gioti

122) Marta Minujin

123) Mary Zygouri

124) Mata Aho Collective

125) Mattin

126) Michel Auder

127) Mike Crane

128) Miriam Cahn

129) Molly McDolan

130) Mounira Al Solh

131) Moyra Davey

132) Naeem Mohaiemen

133) Nairy Baghramian

134) Narimane Mari

135) Nathan Pohio

136) Neil Leonard

137) Nelli Kambouri

138) Neni Panourgiá

139) Nevin Aladag

140) Niels Coppens

141) Nikhil Chopra

142) Niklas Goldbach

143) Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat)

144) Nilima Sheikh

145) Nomin bold

146) Olaf Holzapfel

147) Olga Tsaplya Egorova (Chto Delat)

148) Otobong Nkanga

149) Oxana Timofeeva (Chto Delat)

150) Panos Alexiadis

151) Peaches Nisker

152) Piotr Uklanski

153) Panos Charalambous

154) Pavel Braila

155) Pélagie Gbaguidi

156) Peter Friedl

157) Philip Bartels

158) Philipp Gropper

159) Prinz Gholam

160) Prodromos Tsinikoris

161) Ralf Homann

162) Raphaël Cuomo

163) Rasha Salti

164) Rasheed Araeen

165) Raven Chacon

166) Rebecca Belmore

167) Regina José Galindo

168) R) H) Quaytman

169) Rick Lowe

170) Roee Rosen

171) Roger Bernat

172) Rosalind Nashashibi

173) Ross Birrell

174) Samia Zennadi

175) Samnang Khvay

176) Sanchayan Ghosh

177) Sandro Mezzadra

178) Sanja Ivekovic

179) Sarah Washington

180) Serdar Kazak

181) Serge Baghdassarians

182) Sergio Zevallos

183) Shu Lea Cheang

184) Simon(e) Jaikriuma Paetau

185) Simone Keller

186) Sokol Beqiri

187) Stanley Whitney

188) Stathis Gourgouris

189) Stratos Bichakis

190) Suely Rolnik

191) Susan Hiller

192) Synnøve Persen

193) Taras Kovach

194) Thais Guisasola

195) Tracey Rose

196) Theo Eshetu

197) Ulrich Schneider

198) Ulrich Wüst

199) Valentin Roma

200) Vasyl Cherepanyn

201) Verena Paravel

202) Vijay Prashad

203) Virginie Despentes

204) Vivian Suter

205) Wang Bing

206) What How and for Whom (WHW)

207) William pope)l

208) Yael Davids

209) Yervant Gianikian

210) Zafos Xagoraris

211) Zoe Mavroudi

212) Zonayed Saki

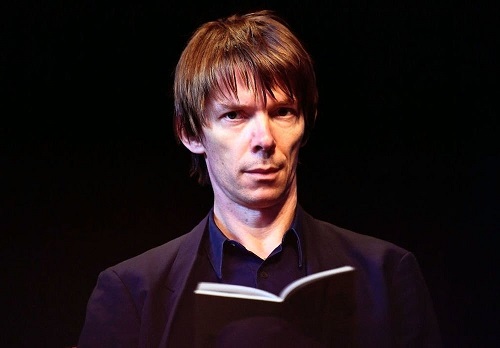

The Artistic Director of the documenta 14, Adam Szymczyk, pictured during the opening press conference at Kongress Palais on June 7, 2017 in Kassel, Germany. Photo by Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images.

Two days after HNA’s report, however, Szymczyk and documenta’s curatorial department counterpunched with an open letter accusing both HNA and local politicians of bending reality like a funhouse mirror. The letter casts its signatories as the victims of a political and media witch hunt fueled by “speculations and half-truths.”

But rather than clearing up the matter, the letter raises even more questions about what the hell happened—not all of them applicable to the exhibition’s critics, either.

From the standpoint of organizational oversight, the open letter’s core claim is that Szymczyk and his colleagues have continually sought and received approval on the exhibition’s budget and dual-city conceit from all “responsible parties” dating back to 2013, before Szymczyk had even been selected as documenta 14’s director. Further, the signatories point out that documenta’s “budget and structural funding has not substantially changed from 2012,” regardless of the current exhibition’s ambitious twin-cities approach.

Nor would any debt owed by documenta’s parent company capture the larger truth of the exhibition’s fiscal impact, according to the letter. Even if ticket sales are indeed slightly depressed in comparison to documenta’s 2012 edition—HNA alleged a dip of three-percent this year—the signatories contend that “the money flowing into the city [of Kassel] through the making of documenta greatly exceeds the amount the city and region spend on the exhibition.”

And even THAT doesn’t fully paint the picture, according to Szymczyk and his colleagues. Because to judge documenta only on its fiscal merits is to miss the point. In their words: “The expectations of ever-increasing success and economic growth not only generate exploitative working conditions but also jeopardize the possibility of the exhibition remaining a site of critical action and artistic experimentation. How can the value production of documenta be measured?”

So, who and what do we trust in this sea of gray?

It’s difficult to say at this stage. An independent audit of documenta 14 won’t arrive until later this coming week, and documenta’s communications department responded to my inquiries by saying that they could “be fully answered by the administration only after the closing of” the exhibition.

This leaves me little choice but to examine the precedents, incentives, and economic rationales that might be animating both sides in this dustup. And after running each one through the same imperfect inquisition, neither documenta nor its antagonists emerges beyond suspicion.

Working backward: Is it possible that documenta really is the target of a politically motivated hit job? Maybe. Politicians have sought favor with the public (or cover from their own errors) by trashing their predecessors for as long as we as a species have been standing upright. And although I’m not well-enough versed in regional and local German politics to offer many specifics, consider these statements from mayor Geselle:

“Documenta is inextricably linked with Kassel… We want Documenta to continue in Kassel as a world-ranking exhibition of contemporary art.”

As Andrew Russeth noted, the 2012 edition of documenta expanded beyond Kassel, but only with “small satellite projects in Kabul, Banff, Cairo, and Alexandria.” Szymczyk, however, took a giant leap forward from that international foothold by effectively exporting half of documenta 14 to a foreign city.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of a local official in Kassel or a regional one in Hesse. The past two iterations of arguably your strongest high-end tourism magnet have established serious momentum toward moving elsewhere—if not entirely, then at least substantially. I don’t think you need to be in the midst of sizing your cranium for a tinfoil hat to wonder if those politicians might be inclined to try slowing or stopping that migration with a little poison press if necessary.

Also potentially relevant is this nugget from Jason Farago‘s review of documenta 14’s Athens program: “The German news media, too, has looked askance at Documenta’s expansion into the capital of what some still offensively call a schuldenland, or debtor country.” This idea gives at least some credence to the possibility that HNA might have an agenda other than good journalism here, too. I mean, not that global nationalism is surging like a lighting-struck electrical line or anything…

Am I saying the HNA story is definitely a plant or a distortion? No. I’m just saying the incentives and precedents don’t rule it out.

Certain details heighten the plausibility of that scenario at least a bit, too. For instance, HNA claimed that the cost of transporting Rebecca Belmore’s work—a life-size marble camping tent titled Biinjiya’iing Onji (From inside)—to documenta 14 rose into the six figures. But a source inside documenta’s curatorial team told Hyperallergic‘s Benjamin Sutton that “the work’s actual shipping costs were only €6,560 (~$7,800) and were entirely covered by the Canada Council for the Arts.”

Who’s telling the truth on this point, and what does it mean for the HNA story as a whole? I don’t know for sure. But I’ve sourced and/or reviewed enough art-shipping quotes in my gallery years to say that if you’re paying €100,000 or more to get a marble camping tent across the ocean, your organization’s dress code must consist of white face paint, rainbow-colored wigs, and floppy red shoes.

All that said: In this vacuum of facts, the most troubling debris flying around the issue still lands on documenta. As far I can tell, the open letter never directly refutes HNA’s report about either the existence of a budget shortfall or its scale. Instead, Szymczyk defense seems to boil down to, “Well, our budget was approved, so how is this our fault?” Which would be naive at best, and disingenuous at worst.