How might the works of Marcel Duchamp, Ai Weiwei, or Barbara Krugerbe received in North Korea, a country notorious for the tight grip its ruling regime keeps on information? Would the images of and ideas behind their work spark new ways of thinking amongst a population reared on a steady diet of state propaganda?

Artist Mina Cheon, a professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), is working to answer those questions. She has successfully sent hundreds of USB sticks containing short videos of contemporary art lessons into North Korea as part of a new art project. The videos will be on view starting October 20th at New York gallery Ethan Cohen as part of “UMMA: MASS GAMES - Motherly Love North Korea,” a solo show of Cheon’s artwork curated by Nadim Samman.

There are 10 lessons, each roughly 10 minutes, with different lessons on different USBs. They provide a thematic history of contemporary art, beginning with Duchamp’s seminal Fountain (1917). Arranged by thematic subjects such as art’s relationship to power, food, feminism, and money, the lessons trace major movements including pop art and abstraction. The episodes are narrated by the artistic persona Professor Kim, the teacherly incarnation of Cheon’s North Korean alter-ego Kim Il Soon.

North Koreans who watch all 10 videos will be introduced to the works of around 50 artists, a varied range that includes several Korean artists, including Cheon, as well as the Guerrilla Girls, Jackson Pollock, Dread Scott, and Damien Hirst. Political work is not the focus of the videos, although it does appear, notably in the work of Ai. Episodes end with assignments, simple artistic tasks that spur creative thinking while remaining conscious of the reality in which North Koreans live. For example, one assignment is for viewers to write down their dreams and “make them come true in abstraction,” an instruction that is left nebulous, to avoid creating anything concrete for the authorities to find.

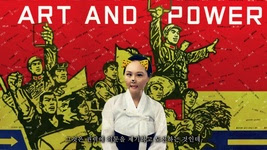

Mina Cheon as Professor Kim. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery and the artist.

Cheon produced the videos in K-Town Studios in Korea Town, Baltimore, where she lives along with Seoul and New York City. They are humorous, light, and fun, featuring Professor Kim in front of a floating backdrop, sometimes with a Snapchat animal filter superimposed over her face. In a gentle tone sometimes accompanied by sound effects, she discusses artworks as their images, interspersed with emojis, clips from The Simpsons, and archival photos, appear on screen.

“I didn’t want it to be propaganda,” said Cheon. “I wanted to present something that’s communicable.”

This luscious and entertaining effect, Cheon said, invokes the aesthetic of the South Korean images and videos that are smuggled into North Korea. Indeed, while the majority of North Koreans lack internet access, the smuggling of illicit material, from food to movies, is more common than many outside the peninsula realize.

The rise of unsanctioned media exploded after what the North Korean government called the “Arduous March”—a famine in mid-’90s that killed between two and three million North Korean citizens. A black market developed to fill the need for food and other supplies, and the rise in market activity resulted in the trafficking of media as well. Today, in some areas of North Korea, it’s possible to view South Korean soap operas on USB sticks 24 hours after they air.

Cheon’s videos took longer to get into the North—roughly about a month, she said, although she used tried-and-tested smuggling techniques to get them into the country. The USBs were transported across the country’s land border with China, and sent from the South via helium balloon, a common tactic often used by those in South Korea to distribute images and videos in the North. Cheon said she’d been presented with evidence of their arrival in the country, and of their circulation within communities of North Korean dissidents living in South Korea.

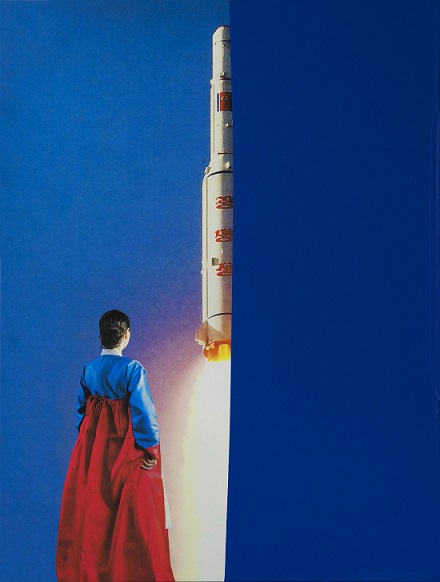

Mina Cheon, aka Kim Il Soon, Missiles Good Bye, Yves Klein Blue Dip painting, 2017. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery and the artist.

When the pieces go on view at Ethan Cohen, they’ll be displayed on Notel Players, the predominant portable media player in North Korea. The devices are extremely popular because they can be charged with a car battery—a must in the electricity-scarce North Korea. They also have a USB slot, which is crucial for North Koreans looking to evade the detection of authorities. Police will cut power to homes, and then inspect DVD players to see if the discs inside are state-sanctioned. USBs can be easily removed and hidden.

Cheon’s latest project is perhaps her most direct engagement with North Korea, but it is not her first. The artist’s work involving the country began in 2004, when she visited the nation during a state-sanctioned trip. Cohen himself has a long history with North Korea. He was the youngest American to visit the country after the Korean War, he said in a statement about Cheon’s work.

“If our governments cannot make détente then we as individuals in society can and must,” Cohen wrote. “I share Mina’s dream [of] bringing art, beyond propaganda, to North Korea.”

In 2014, Cheon filled Cohen’s gallery with 10,000 Choco Pies, basically Korean Twinkies. The candy had become the hottest product on North Korea’s black market after they were used to pay workers at a now-defunct factory that was jointly operated by the North and South. Like much of Cheon’s work, Eat Choco-Pie Together explored and encouraged cultural exchange and showed Korean cooperation.

“I’m always astonished at the disparity between what the Western media would say about Korea versus what was really going on within Korea,” Cheon said. She’s extremely critical of how North Korean citizens are perceived and represented in the West, and how their lives are often spoken about only in the context of curbing North Korea’s nuclear program. Cheon’s videos to the North include reminders that people across the world do think and care about them, no matter what the state’s propaganda says.

“This is how contemporary art might start in North Korea,” said Samman, who curated the exhibition. Art circles have managed to flourish under autocratic government in the past, Samman notes. Conceptual art had strong followings in Hungary and in other parts of the Soviet bloc under Communism. Maybe a group in North Korea, inspired by contemporary art, will start creating work and images beyond what is government-sanctioned. Maybe they already have.

The idea is a remarkably hopeful and humanizing one at a time when tensions with North Korea are at their highest in recent memory and threats from both sides grow increasingly bellicose. The way the project speaks directly to North Koreans is people is a crucial reminder of their humanity at a moment when the President of the United States has threatened to wipe the country off the map. As the exhibition title “Motherly Love North Korea” hints, Cheon’s work speaks with a language that is very different from the saber-rattling, masculine statements delivered in the current crisis.

Cheon dreams of peace on the peninsula, but has realistic expectations for her project. According to the artist, the Korean-language Voice of America radio station (which Cheon has been on in the past) will broadcast a story on the USB art lessons into North Korea, to let people there know about the lessons and why they’re circulating. Cheon doesn’t think the videos will topple the North Korean government. But as the trickle of information into the country becomes a flood, contemporary art lessons could, she said, be the “catalyst” for something greater.

—Isaac Kaplan