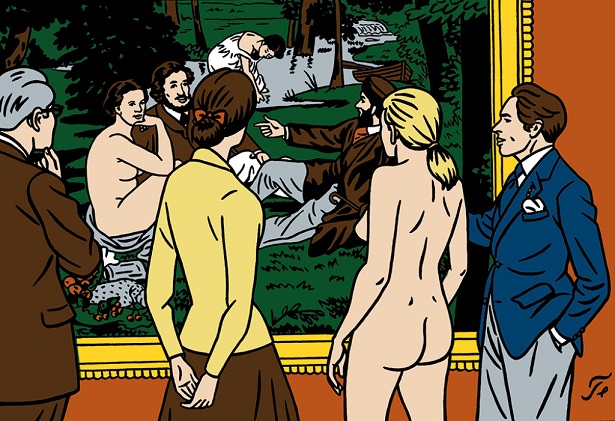

Welcome aboard the long-haul appropriation train, tooting its discontents and satisfactions at its many stops along the way. After all, what does it mean to borrow—an idea, a work, a word or two, an image? And what does it mean to steal?

In his new book, Beg, Steal & Borrow: Artists Against Originality (Laurence King), British art critic and journalist Robert Shore speculates on the knotty questions and comes up with—unsurprisingly—nothing definitive. Ultimately, there are no absolute answers—just stations and ambiguities along the way. Beg, Steal & Borrow is a jolly, informal, journalistic romp through art history, with a focus on the 20th and 21st centuries, picking up everyone from Picasso to Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, and even flagrant copycat Eric Doeringer, who parked himself outside Chelsea galleries with his own renditions of contemporary “icons” (in various sizes) until he was ordered to cease and desist.

Andreas Schmidt, Francis Bacon, from the series “Fake Fake Art,” 2012, reproduced in Robert Shore’s Beg, Steal & Borrow: Artists Against Originality (Laurence King).

COURTESY THE ARTIST

The book is dotted with pithy quotes and aphorisms from critics, poets, other cultural figures, and, of course, artists, such as Mexican conceptualist Jose Dávila, who proclaims, “A new (old) formula for creativity: Banish the blank page. Begin with a sheet overflowing with someone else’s thoughts, images, words. Erase, rephrase, redact, resuscitate—and create something new,” and then this novel “scientific” assessment from Jeff Koons, the multiply-alleged plagiarist, who explains, “I’m a different human being since I saw Manet’s work, my genes have changed and it’s a fact that through ideas you can morph your genes.” So the genes did it?

We are introduced to a wide spectrum of activity, skirting or flirting with the law by the likes of famous provocateur Richard Prince and, of course, Duchamp and Warhol. When asked how he made his flower paintings, Warhol would tell people to direct the question to his most literal copyist, Sturtevant.

Shore shocks with side-by-side texts showing Shakespeare pilfering phraseology from Plutarch, and naturally, who knows where the world’s culture would be without the bard to steal from. And he takes note of German photographer Michael Wolf’s 2011 book Real Fake Art (written just before fake news became the trope of the day). Wolf included photographs of lines of Chinese artists each copying a famous painting. When the copies were complete, Wolf hung them up on clothespins to dry and photographed the artists alongside their work, creating his own new artworks.

Finally, Shore reminds us of the obvious: “The Digital Age is the Sharing Age. Online, people will ‘share’ your work and ideas whether you want them to or not.”

As for how that applies to the art world, “In the art world, and particularly the contemporary, digitized globalized art world, for every iteration there’s a seemingly infinite number of modified reiterations—successful memes spreading from brain to brain (and, in the case of internet memes, from computer to computer) propagating themselves through a process of continuous mutation and blending.”

We are left to wonder: If we know we’re doing and saying and/or meaning something different from the original when we replicate an image or appropriate an idea, are we entitled to do it? (After all, according to U.S. law, transformation can justify an artist’s use of copyrighted work.) Should we be?

Peter Soriano, CRESTA e (detail), 2017, aerosol and acrylic paint, installation view.

COURTESY CIRCUIT

A Light Touch

There’s nothing begged, borrowed, or stolen about Philippine-born French-American conceptual artist Peter Soriano. He’s an original, staking out his own claim, continuing to pursue his somewhat un-categorizable path. He draws on walls to his own rhythm and sends viewers this way and that with arrows and other signs—often in contradictory directions.

Soriano provides written instructions on the walls for how to navigate his works and provides drawn directives for assistants to fabricate and reproduce. It’s at once show and tell, thought and substance, yielding what might best be described as interior landscaping. Graffiti, poetry, geometry, and architecture combine to set the scene while the writing and drawing on the walls send signals.

This is art that speaks to our times: It is noncommittal, conceptual, and sculpturally suggestive but not solid. Nothing is solid, but everything is described.

For an exhibition at Circuit Centre d’Art Contemporain, in Lausanne, Switzerland, through October 28, Soriano’s improvisational wit and observational narrative are on display in his measurements of shadows and changing light.

For his 2015 show at the Colby Museum of Art, in Waterville, Maine, and, subsequently, his 2016 installation of three murals and related drawings at the New York gallery Lennon, Weinberg, he mapped a series of mental and physical routes that could be followed and replicated by himself or by anyone else.

“I’ve always been interested in lightness and in things that were in between two things,” he told me, mentioning Italo Calvino’s essay “Lightness.” “My working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities; above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language.”

He travels light. He could, he said, “carry around a few notebooks to make 90 feet of wall.” And, he noted, “You have shadows—you can pick any days and chart the shadows—I’ve always been drawn to shadows. They describe space and yet, they’re nothing.”

He began his career making Fiberglass two-dimensional sculptures. “I was interested in things that could be dismounted and located somewhere else,” he said. But “the more I was interested in pursuing lightness, I asked myself, what exactly was behind lightness?”

It became clear to him, he said, “that I had to rid myself of shape. The sculpture itself became the subject rather than the object.” What, he asked rhetorically, are objects? “They are the things I see.”

He acknowledged, “I still remain pretty much a sculptor. And the shape remains.” But he said, “I describe my relation to whatever is happening. Light, air movements,” using the most appropriately delicate and fragile of mediums, spray paint. “You have a lack of control—air would change it.”

“I’m trying to make a language,” he summed up, using symbols, arrows, parentheses, numerals, and the dotted line, reminiscent of Guston and Miró, but really not like them at all. He’s just talking his own talk, and walking it too.

Installation view of “Nathalie Du Pasquier: BIG OBJECTS NOT ALWAYS SILENT,” 2017, at Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania.

CONSTANCE M (2)

Nice Work If You Can Get It

Where Soriano’s penchant is for lightness and ephemerality, the legendary Italian design collective Memphis applied a solid Pop imprimatur to objects, images, and ideas. Celebrated recently at the Met Breuer, founder Ettore Sottsass had a truly post-modern sensibility—playful, emotional, historical, contrarian, and most of all declarative.

Sottsass passed away in 2007, but the French artist and designer Nathalie du Pasquier, also a founding member of Memphis, has picked up the baton and continues to riff on Memphis in a more painterly mode, most recently on the walls, floors, and ceiling of Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art.

Du Pasquier’s world is more personal and cerebral than Sottsass’s. Memories and the breadth of the imagination weigh in assertively. Painted on the walls and ceiling, du Pasquier’s pictures are replete with fat-looking objects posed full frontal and looking as if they might tumble onto the floor. They tell playful, show-and-tell-style tales with an almost Proustian effect, activating all manner of associations. One work, for example, titled My House is a huge box—a shelf covered with her objects in a Duchampian act of documentation.

Du Pasquier’s environments inhabit a world, filled with paintings, rugs, machines, and videos, all looking for a place to nest. It’s Botero meets Morandi: extroverted and introverted, funny and seductive, outspoken and impenetrable.

Copyright 2017, Art Media ARTNEWS, llc. 110 Greene Street, 2nd Fl., New York, N.Y. 10012. All rights reserved.