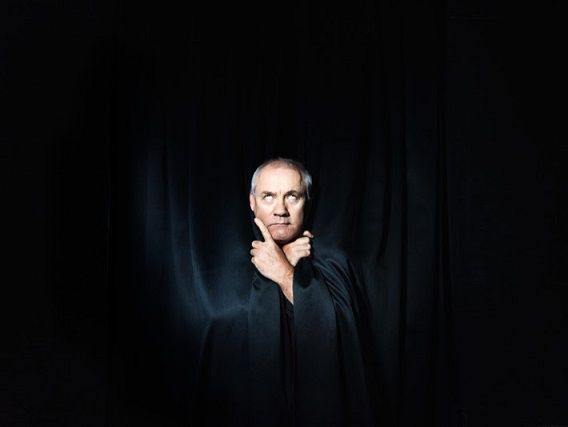

Damien Hirst at Palazzo Grassi. In foreground, the sculpture “Demon with Bowl.” Photo: Andrea Frazzetta/INSTITUTE

The question of time was something Hirst had begun to think a lot about back in 2006, when he quit drinking. All his work started to feel like responses to the demands of the moment; every show he did, he said, always felt like a mad sprint to a finish line.

“I had found myself in this world where all these hedge-fund guys were becoming billionaires and everybody was buying everything I made,” he said. “It’s quite difficult to make art in that situation. Things are a lot easier to make [when] people are not buying your work. It became quite crazy; I’d start making another spot painting and a guy would buy it and I’d make another spot painting and a guy would buy it. It was a very quick turnover in terms of objects and art and ideas, and it started feeling a bit alien to me. The auction was really the combination of all that.”

The defining piece of the Sotheby’s sale was also its highest seller: The Golden Calf, a gold-hoofed, gold-horned bullock in a tank of formaldehyde on a marble plinth (and of course the Bible’s ultimate iconic no-no). “I was thinking about the money corrupting the art in some way and trying to celebrate that somehow, like I had done with the diamond skull. But I was also thinking about drawing a line across it — ending it.

“This show is much more, I don’t know — a bit older and a bit wiser. I was sort of thinking, Fuck, I can’t be just the guy who does a diamond skull and then does a diamond fucking penis.”

The ten-year production period stemmed from a landscaper’s remark about how slowly trees grow. The shipwreck-discovery concept, he said, arose from spending time at the undersea archaeology wing of Monaco’s Oceanographic Museum, where he exhibited work in 2010. One major inspiration was listening to A History of the World in 100 Objects, the British series of podcasts (and subsequent book) narrated by Neil MacGregor, the former director of the British Museum. The premise of the series was that the story of humanity could be better expressed through what we made than what we wrote, an idea that became central to “Treasures.”

Except Hirst made his own history for the show, an account of humanity that owes as much to Hollywood as to Ovid. He said the giant scorpion and Hydra monster are right out of the 1981 Clash of the Titans, which set the bar for bastardizing mythology when the Greek god Zeus famously summons … a Norse monster, the Kraken. And in one of the show’s most massive iconic pieces, the seven-snake-headed Hydra does battle with the multi-armed Hindu goddess of death, Kali.

And while one might have expected Hirst to make a massive shrine to Mercury, the Roman god of pranksters, thieves, and merchants, he didn’t want his fascination with antiquity to take over completely. So while there is a figure of Mercury, he’s about as big as a toy soldier. A coral-covered Mickey Mouse gets much more play. “I probably identify more with Mickey Mouse than Mercury.”

The artwork “Proteus” by Damien Hirst. Photo: Andrea Frazzetta/INSTITUTE

“Treasures” opened at a time when the art world’s relationship to money has become more vexing than ever — witness the reaction to the recent sale of the $450 million Leonardo — and performance art, which isn’t monetized as easily, has been getting more and more attention. At this year’s Biennale, the most-talked-about piece was a dark performance by Anne Imhof that took place on a glass platform behind a security fence and frenzied Dobermans. Yet Hirst’s show had its own kind of topicality, speaking not to the security state and anti-immigration policies but to the Venice of 2017 — and 1517. Five hundred years ago, Venice was of course the richest country in Europe, capital of the thriving trade between Europe and Asia. In many ways, it was in Renaissance Venice that the modern concept of a cultured life (with all its trappings) was born and developed, as Lisa Jardine chronicled in her 1996 book, Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance.

Fittingly, half of “Treasures” is installed at the Punta Della Dogana — built centuries ago as Venice’s customs house, the sluice through which oceans of treasures flowed. It and the other venue, the Palazzo Grassi, are owned by François Pinault, a billionaire collector of Hirst’s work who also owns Gucci and Christie’s. And what better place for a show about sunken treasure than on a sinking treasure: a city standing on unstable foundations, overwhelmed by 20 millionplus tourists a year, in battle with the sea. If Mickey Mouse seems out of place on the Grand Canal, how about that cruise ship outside St. Marks Square that looks as tall as the campanile?

Hirst is a fan of titles that can be read in multiple ways, and so the “Wreck of the Unbelievable” is the story of Cif Amotan II, it’s the spectacular folly of this show, it’s the city of Venice (or Miami Beach, where no cost was spared in September as Irma approached to protect a 2014 Hirst sculpture of a gold-leafed woolly-mammoth skeleton encased in glass outside the Faena hotel. Its title: Gone but Not Forgotten). It’s humanity itself, shooting for immortality and flirting with apocalypse.

“The sea is the closest thing on Earth to outer space, and I wanted to create a story that felt like another world,” said Hirst. “But at the same time, with global warming, you have sea levels rising — and you can’t think of a shipwreck without thinking of the end of the world. If you stumble back in time, you see that human beings are pretty fucked up but that they also achieve amazing things, and I sort of oscillate between those two.”

As far as how “Treasures” will ultimately be remembered, Hirst said that the show’s long production time gave him perspective.

“My business manager said to me when we were just about to start the installation, ‘At what point will it be a success for you? At the opening? When the press comes out?’ And I said, ‘It already is.’ At that point, in this instant, I’d already achieved all the things I wanted to achieve. When you make art, if you’re making it properly, you’re really thinking about people that haven’t been born yet. So after ten years working on it, I was pretty impenetrable from the critical point of view.”

He plans on the collection having a long life. He’s already looking for a potential museum space somewhere — probably another port city — to house his entire set of “Treasures” artist’s proofs.

And he recounted a conversation he had once with David Hockney. “He said, ‘Do people often ask you how long your art works last?’ ” Hirst recalled. “And I said, ‘Yes.’ Because he’s a painter, he doesn’t get asked that. So then he said, ‘Do you know what you should tell them?’ and I said, ‘What?’

“And he said, ‘Longer than you.’ ”

*A version of this article appears in the December 11, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.