Ephemera provides an important history lesson, especially for a war that is disappearing from America’s collective memory, but the most affective works in World War I and the Visual Arts are those that convey the pathos of the war experience.

Installation view of World War I and the Visual Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

World War I and the Visual Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art can easily go unnoticed, in the shadow of the museum’s Michelangelo drawing show and other major exhibitions. That would be unfortunate; while relatively small — it occupies four mid-sized rooms in the print wing — its tour through the first modern war provides insight into the conflict’s early reception and the physical and psychological toll it took on each nation involved.

Drawn primarily from the Met’s collection, the exhibition encompasses art, documentary photography, and ephemera and artifacts, the latter ranging from propaganda posters to textiles to gas masks, and brings together artists and perspectives from various nations. It is organized chronologically by room — The Outbreak; No-Man’s-Land; The Aftermath; and a smaller section, The Intersection of Arms and Art — a schema that risks an oversimplified narrative, but the modernity, austerity, and raw power of much of the art predominates.

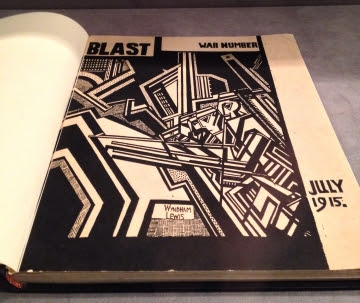

International modernisms are represented in works by artists including Gino Severini, Wyndham Lewis, Fernand Leger, Otto Dix, and Marsden Hartley. While pieces such as Lewis’s geometric machine gunners for the cover of the periodical Blast (July 1915) and Severini’s charcoal drawing “Flying Over Rheims” (1915) toe the Futurist/Vorticist line of technological dynamism, Severini’s “Still Life: Bottle + Vase + Journal + Table” (ca. 1914-15), which collages a charcoal and gouache abstraction with newspaper clippings on French military actions, brings a level of social commentary to the image.

Wyndham Lewis, cover of Blast (July 1915)

In many cases, the most effective works are the simplest. Belgian artist Léon Spilliaert’s poignant 1917 watercolor, gouache, and graphite painting “Rockets” transforms flares into a constellation of stars illuminating an indigo sky. Japanese-American artist Kerr Eby portrays an explosion with an expanse of negative space consuming almost the entire upper half of his drypoint print “A Kiss for the Kaiser” (1919). Eby’s mezzotint and drypoint print “No Man’s Land — St. Mihiel Drive” (1919) is more evocative, as its soft, deep gray washes over the sky, veiling troops below.

Three 1914 charcoal drawings by Marsden Hartley confirm the artist as one of America’s great modernists. The drawings — memorials to his close friend and rumored lover, Karl von Freyburg, a German officer killed early in the war — belong to a suite of works produced between 1913 and 1915 in Berlin, which also includes lush, colorful paintings. The abstraction of military insignia and symbols echoes the paintings, but the black and white palette pares down the visuals, rendering the drawings almost elegiac.

These works demonstrate how modern American artists were a century ago, with the international reach of modern art having already arrived on our shores. They serve as counterpoints to the traditionalism of official propaganda art, as well as the nationalism and, often, xenophobia found in posters and periodicals — many of which reveal the extent to which nationalism bolstered the war effort on both sides. While Allied nations characterized Germans as subhuman “huns” and beasts (as in the famous 1917 King Kong-style poster proclaiming “Destroy This Mad Brute: Enlist” by the American artist Harry Ryle Hopps), Germany and other Central European nations engaged in an equivalent mocking and bestializing of the enemy.

The ephemera provide an important history lesson, especially for a war that is disappearing from America’s collective memory, but the exhibition’s most affective works are those that convey the pathos of the experience.

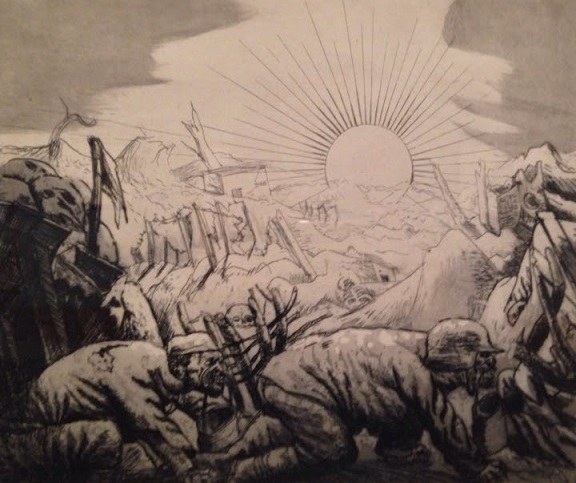

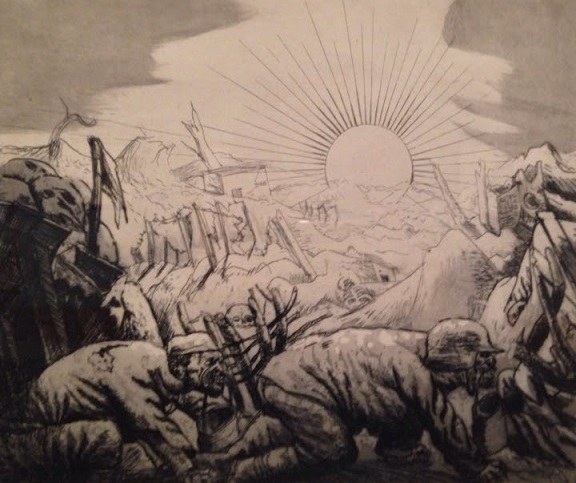

Christopher R.W. Nevinson, “That Cursed Wood” (1917)

British artist Christopher R.W. Nevinson is particularly well represented. An early acquaintance of F. T. Marinetti and Wyndham Lewis, he diverges from Futurist and Vorticist influences in his print, “That Cursed Wood” (1917), a bleak image of dead trees emerging from the pockmarked ground, as biplanes circle overhead like ravens in the gray sky. Another impression of the ruined earth, Edward Steichen’s photograph “Aerial View of Vaux, France, After the Bombing Attack” (1918) shows the city as so much rubble. Cropping out the sky entirely, Steichen refuses the viewer a way out of the destruction.

More intimately than Steichen’s image, Margaret Hall’s photograph “Grave in ‘No Man’s Land’” (1918-19), taken while volunteering for the Red Cross in France, turns on hope, depicting a lone woman mourning over a cross marking a grave.

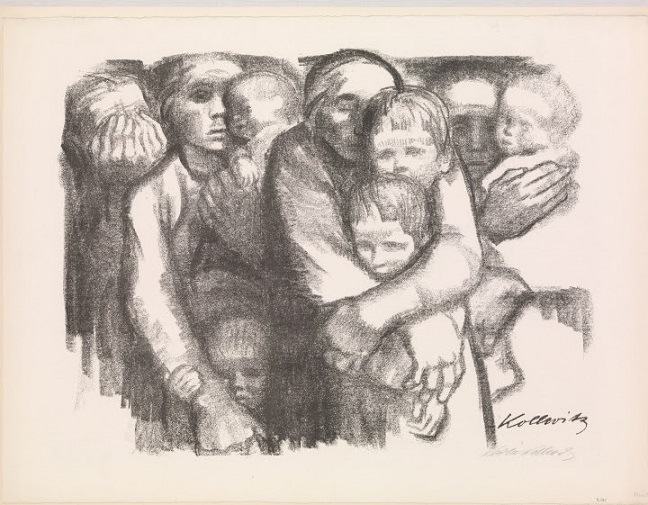

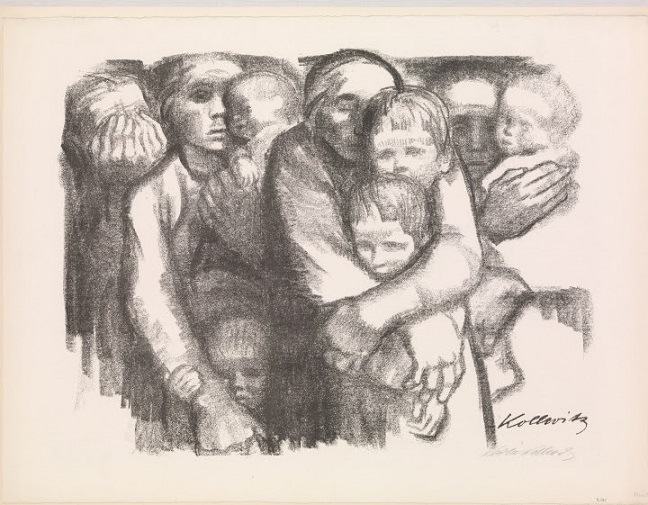

Hall is also one of the few women included in this or any WWI exhibition, and it is to the museum’s credit that she is here, along with Russian artist Natalia Goncharova, represented by lithographs from her portfolio Mystical Images of War (1914), and Germany’s pacifist mother, Käthe Kollwitz.

Käthe Kollwitz, “Mothers” (“Mütter”) (February 1919), lithograph (courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928)

Kollwitz, who initially supported the war, denounced it after the death of her son, Peter. The Aftermath section features Kollwitz’s lithographs “The Mothers” (1919) and the mournful “Killed in Action” (1920), as well as works by Ernst Barlach, Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and complete print portfolios by Otto Dix and George Grosz.

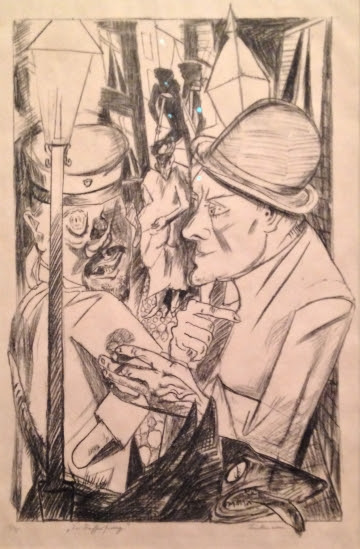

German artists dominate this section, with images of pain and loss — of lives, means, and faith. Beckmann’s “Two Officers” (1915) depicts close-up the stern, bourgeois faces of two men; the encounter is simultaneously distant, as the men look away from each other and the viewer, and intimate. In “The Way Home,” from the 1919 portfolio Hell (Die Hölle), a man (modeled on Beckmann) assists a maimed and facially disfigured veteran in finding his way home while two men on crutches appear as shadows in the background of the claustrophobic composition. The veteran — mirrored in a nearby 1916 medical illustration by Rodin for facial and jaw reconstruction — stands in for the many disabled soldiers roaming the streets of Berlin or hidden in hospitals outside the city after the war.

Max Beckmann, “The Way Home” (1919)

In his satirical 1928 portfolio Background (Hintergrund), George Grosz skews punditry with a combination of vitriol and nihilism. For a print titled “Soon Again: ‘The More Cruel, the More Human,’” he grants a skeleton armed with a gas tank a swagger that seems to say, “kill and be killed.” A frequently reproduced lithograph, “German Doctors Fighting the Blockade” from his portfolio God with Us (Gott mit Uns, 1918, published 1920), depicts a portly military doctor examining a standing, bespectacled skeleton. Declaring the skeleton “KV” (kriegsverwendungsfähig, or “fit for active service”), the doctor’s punchline is both funny and grotesquely shocking.

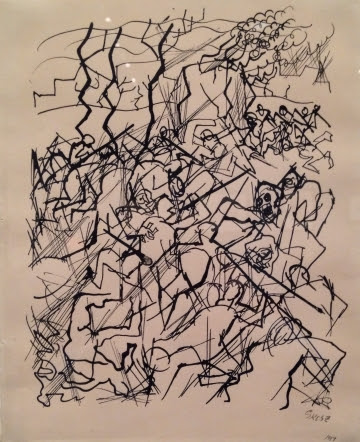

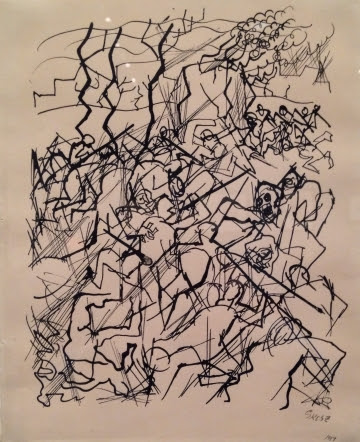

Accompanying Grosz’s prints is the 1917 ink-on-paper “War Drawing.” The composition is a tangle of jagged black lines, suggesting barbed wire and dead trees, overlaid with marching stick figures and plumes of smoke. A chilling face at the far right edge — mouth gaping in a cartoonish scream — reduces the chaos to a moment of deathly fear.

George Grosz, “War Drawing” (1917)The most compelling reason to see World War I and the Visual Arts is Otto Dix’s spectacular, harrowing series of etchings, The War (Der Krieg, 1924). The exhibition includes all 50 prints that comprised the published portfolio, a rarity in itself, as well as a 51st print censored by Dix’s publisher, “Soldier and Nun (the Rape).”

Installed in three rows on one wall, the etchings cycle through battlefields and barracks of the Western Front. (The wall text does not include the titles of individual prints, which provide dates, places, and some context.) Dix, who served in a Saxon machine gun unit on the Western and Eastern Fronts, incorporates small details and art historical references in the images, some of which can only be discerned at close range.

Otto Dix, “Ration Carriers near Pilkem” from The War (1924)

Amid the ghostly moonlight and shadows surrounding a cross and disembodied leg in “Soldiers’ Grave Between the Lines,” the opening print, rats crawl in and out of holes in the earth; the blackened and bloated hands and faces of casualties in “Gas Victims (Templeux-La-Fosse, August 1916)” show the effects of chlorine gas on the body; in the final print, “Dead Men before the Position near Tahure,” dog tags identify a decomposing corpse as a Corporal Müller from Cologne.

The War exponentially enhances and complicates World War I and the Visual Arts. Dix contributed more to the visual representation of war than any other artist in the 20th century, but his contributions — most of all The War — are as paradoxical as the war. Although his work is most often aligned with pacifism, it can be and has been seen as a glorification of warfare, yet it belongs to neither pole. Dix’s war is bizarre and nightmarish and traumatic, but it is not simple. He saw in his experience the human drama and his greatest achievement, which the Met gives us in full, is to confront it.

World War I and the Visual Arts continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan) through January 7.