“Only five or six years ago you could still buy one of these canvases for less than 10,000 pounds [$13,476], says Hannah O’Leary, the head of Sotheby’s modern and contemporary African Art department, a division that was created last year. “Certainly, in the last 12 to 24 months, we’ve had a surge of people desperate to acquire her pieces.”

Call it a market trend or call it simply a long-overdue recognition of heretofore overlooked artists, but Yiadom-Boakye, who was born in 1977, joins a select group of peers from the African diaspora, including Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Kerry James Marshall, whose paintings have recently surged past $1 million at auction.

“She’s a great artist, first of all,” says O’Leary. “But the fact that she is a woman, she is black, she is of the African diaspora—these are all things that the [art] market is turning toward.”

It’s not as if Yiadom-Boakye has been hiding or is unknown to many in the art world since she graduated from the Royal Academy in London’s MFA program in 2003.

An installation view of the solo show “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Under a Song for a Cipher” at the New Museum in New York, which ran from May 3 through September 3, 2017.Photographer: EPW STUDIO

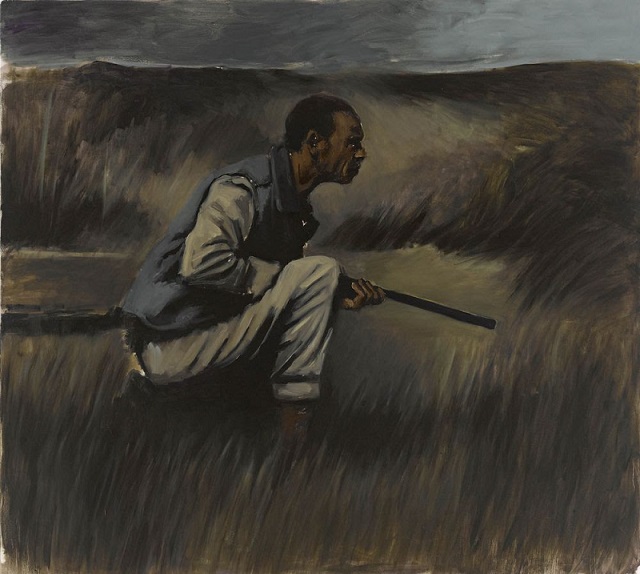

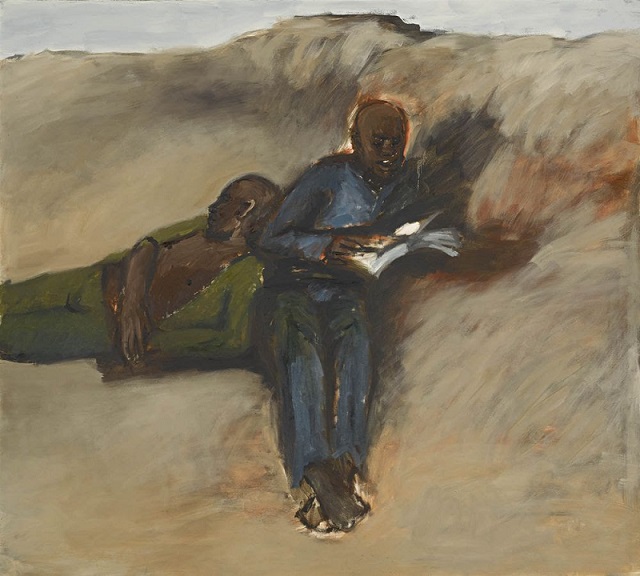

While her style has evolved over the past 10 years, Yiadom-Boakye has consistently painted large-scale oil portraits of people she paints from her imagination. Drawing on established stylistic precedents—Manet and Goya are often evoked—she developed a distinct aesthetic with deep, saturated colors and dynamic figures.

“She’s an extraordinary painter,” says Tamsen Greene, a senior director at New York’s Jack Shainman gallery, which has represented Yiadom-Boakye since 2009. “She’s made her own, unique style, but she uses this classic, incredibly formal visual language that draws people in.”

By 2007, Yiadom-Boakye had been included in an array of group shows, including the Tate Liverpool Biennial and the Saatchi Gallery’s Triumph of Painting Part 6, and in 2010 the Studio Museum in Harlem gave her a critically acclaimed solo show. She’s since been a subject of solo shows at the Serpentine Gallery in London (2015), the Kunsthalle Basel (2017), and the New Museum in New York (2017).

“Since the day we’ve started working with her, there’s been a great deal of demand,” says Greene. “We’ve always had to manage a wait list.”

That could partially be due to Yiadom-Boakye’s core group of prominent collectors, who have been vocal supporters of her career by lending her work to exhibitions whenever possible.

The Hours Behind You, 2011, by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.Source: Sotheby’s.

Those collectors include former NBA player Elliot Perry and his wife Kimberly, the German hair-care heir Thomas Olbricht, the Belgian collecting couple Wilfried and Yannicke Cooreman, the Japanese industrialist Hiroshi Taguchi, and the American philanthropist and collector Pamela Joyner.

“The people who live with her work love it,” says Greene. “It’s not rare that someone acquires a work and then immediately wants to acquire another one.”

Breakthrough

For all that, it took nearly a decade for a single painting by Yiadom-Boakye to come up to auction, when her work Politics, which was made in 2005, was put on sale at Sotheby’s in London in 2010 with an estimate of 15,000 to 20,000 pounds. It sold for 52,500 pounds with premium.

The next day at Christie’s London, another one of her paintings sold for 146,000 pounds above a high estimate of 50,000 pounds, and the day after that, also at Christie’s London, another painting sold for 116,553 pounds over a high estimate of 15,000 pounds.

“We, along with her London gallery, do everything we can to place her work in collections that are going to be good stewards,” says Greene. “A lot of the works that go to auction predate her work with either of her galleries.” (The three works that came to Sotheby’s in November were from the estate of the collector Jerome Stern, who died in April.)

An installation view of the show at the New Museum.Photographer: EPW STUDIO

O’Leary credits Yiadom-Boakye’s secondary-market breakthrough to the New Museum show earlier this year. “She was really in the London auctions,” she says. “But we can attribute a lot of her success to her newly raised profile in the U.S.”

The inevitable question—whether her new status in the art market can be sustained—has already been answered, Greene says. “She’s not a new artist. She’s had important solo shows, and I don’t see why that would change,” she says.

“I think all the market frenzy is just a testament to the work.”