Kynaston McShine, Pioneering Curator of Vanguard Art, Dies at 82

MARC OHREM-LECLEF/MOMA

“If you are an artist in Brazil, you know of at least one friend who is being tortured; if you are one in Argentina, you probably have had a neighbor who has been in jail for having long hair, or for not being ‘dressed’ properly; and if you are living in the United States, you may fear that you will be shot at, either in the universities, in your bed, or more formally in Indochina,” the curator Kynaston McShine wrote in the catalogue for his 1970 exhibition “Information” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

“It may seem too inappropriate, if not absurd,” he continued, “to get up in the morning, walk into a room, and apply dabs of paint from a little tube to a square of canvas. What can you as a young artist do that seems relevant and meaningful?”

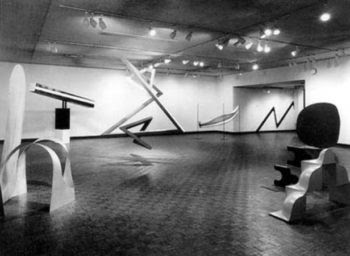

McShine answered that question in his storied exhibition by showing an international cast of artists who blurred the lines between mediums, reached out to the general public, and relentlessly experimented in countless other ways—feverishly seeking new means of communication. Hans Haacke polled visitors on their views about the support of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, then a MoMA trustee, for the Vietnam War. Rafael Ferrer left 50 blocks of ice, each 300 pounds, to melt in the museum’s sculpture garden. Vito Acconci had his mail forwarded for display in the show.

Installation view of “Information” at MoMA, 1970, with a work by Walter De Maria at left.

MOMA

“These artists,” McShine wrote, “are questioning our prejudices, asking us to renounce our inhibitions, and if they are reevaluating the nature of art, they are also asking that we reassess what we have always taken for granted as our accepted and culturally conditioned aesthetic response to art.”

Over the course of more than 50 years, McShine devoted himself to those pursuits, organizing exhibitions that highlighted the most venturesome and radical of his era. His death at the age of 82 brings to a close one of the great, essential curatorial careers of the postwar era.

McShine was born in 1935 in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and received his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Dartmouth College in 1958, joining MoMA’s department of circulating exhibitions the next year, after undertaking graduate studies at the University of Michigan. (He continued his graduate work at the New York University Institute of Fine Arts, and later taught.)

Installation view of “Primary Structures” at the Jewish Museum, 1966.

THE JEWISH MUSEUM

In 1965, he moved two-and-a-half miles uptown from MoMA, to the Jewish Museum, to become curator of painting and sculpture, and the next year he put together “Primary Structures,” a show of geometric abstract sculpture that is widely regarded to have involved the first major presentation of Minimalism in the United States. Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Anthony Caro, Donald Judd, and Anne Truitt were among its 44 artists. In 1967, he organized an Yves Klein retrospective and became the museum’s acting director, a position he held until MoMA hired him back, as associate curator of painting and sculpture, the next year. He would remain at the museum for a full half-century, retiring in 2008 as chief curator at large.

At the time of his hiring at MoMA, in 1968, McShine was the only person of color serving as a curator at a leading art museum in the United States, according to a New York Times article from the time cited by Susan E. Cahan in her 2016 book Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power.

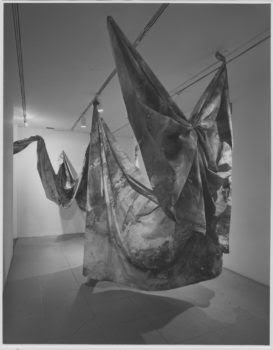

Installation view of “Projects: Sam Gilliam” at MoMA, 1971.

MOMA

In 1970, “Information,” with its emphasis on conceptual, political, and generally outré-minded art, secured McShine his place in the curatorial pantheon. He was 35. One year later, he initiated MoMA’s “Projects” series of shows that are devoted to emerging artists, with Keith Sonnier first out of the gate, followed by bleeding-edge figures like Mel Bochner, Sam Gilliam, and Nancy Graves.

Around that same time, McShine penned a memo suggesting a show from MoMA’s holdings that would highlight works “which have enriched our collection as a result of Hitler’s Entartete Kunst campaign,” according to Cahan. That proposal was purportedly a bit too radical for the administration at the time, but it grew into a show, titled “The Artist as Adversary,” of politically engaged artwork from the collection.

McShine remained a force for vanguard contemporary art throughout his time at MoMA, an institution not always known for its enthusiastic support for the field, and in 1984 he organized “An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture,” an exhibition with more than 150 artists that marked the reopening of the museum after renovations. ”The show is a sign of hope,” said Kynaston McShine told the Times that year. ”It is a sign that contemporary art is being taken as seriously as it should be, a sign that the museum will restore the balance between contemporary art and art history that is part of what makes the place unique.” (The next major survey of contemporary painting would not arrive until 30 years later, with Laura Hoptman’s “The Forever Now.”)

Installation view of “Marcel Duchamp” at MoMA, 1973.

MOMA

In 2002, when MoMA closed its Midtown Manhattan headquarters for another renovation, McShine, came, in some peculiar sense of the term, full-circle, organizing the museum’s permanent collection showcase at a temporary location in Queens. ”We are trying to keep some of the museum’s atmosphere in a smaller space,” McShine said in an interview at the time. ”We want to make it a lush and pleasurable experience.”

He also put together major retrospectives at MoMA, alone or in partnership with other curators, for artists like Marcel Duchamp (in 1973), Joseph Cornell (1980), Andy Warhol (1989), and Richard Serra (2007)

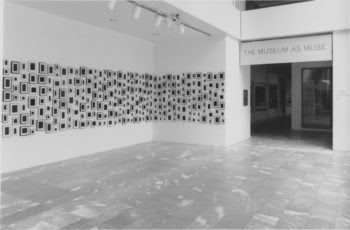

Throughout his myriad projects, McShine’s curatorial methodology was always boldly open to new ideas, and intent on trying executing them—with a focus on artists’ visions. Fittingly, one of his most enduring legacies is his 1999 group show “The Museum as Muse: Artists Reflect,” which looked at the rich history of artists who closely examined and gamely tested museums. Louise Lawler showed her gimlet-eyed photos of art in its various environments, and Michael Asher published a modest book that aimed to document MoMA’s deaccession history. It’s a show that one still hears artists, dealers, and curators discuss reverentially.

Installation view of “Museum as Muse” at MoMA, 1999, with works by Allan McCollum at left.

MOMA

At the end of his catalogue essay for that show, McShine wrote, “Like two superpowers that mutually respect each other, even mutually depend on each other, artists and museums nevertheless watch each other vigilantly—as if practicing for the field on which they are engaged together, the miraculous field of visual art.”

A few words stand out now in that elegant formulation when thinking of McShine’s work: respect, vigilantly, and, more than any other, miraculous.