Can an art exhibition make resistance catchy and seductive? Surely that’s too much to ask of any one show, but the fourth edition of the New Museum’s triennial, Songs for Sabotage, makes a valiant go of it.

Unlike in previous editions, the co-curators of this exhibition — Gary Carrion-Murayari of the New Museum and Alex Gartenfeld of Miami’s Institute of Contemporary Art — have left the work plenty of room to breathe, with a relatively manageable 80 pieces by 30 artists and collectives spanning three upper floors and the ground level of the museum. Previous triennials have been organized around themes of youth, international pluralism, and the digital; this one, if it has to be boiled down to a semi-concise phrase, is about localized forms of political resistance.

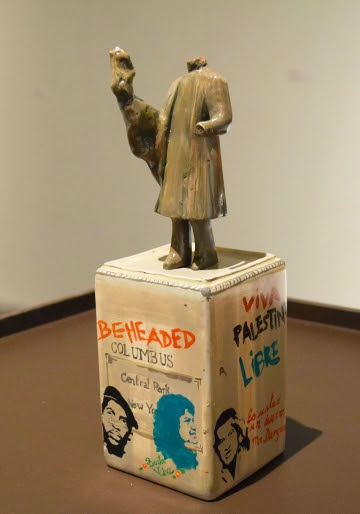

Daniela Ortiz, “Columbus (Colón)” (2018), ceramic and paint

“For all of their disparate geographic locations, the artists in this show are keenly aware of the networks of political and economic power that connect them, and the ways in which these networks are written on top of pathways of domination and exploitation that stretch back long into the past,” co-curator Gary Carrion-Murayari of the New Museum said at a press preview yesterday. “These artists are 30 new voices, but they’re dealing with very, very old problems: the painful and difficult legacies of colonialism; the historical erasure of the victims of state violence; and engrained forms of institutionalized racism that haunt the ways individuals live and work; to name just a few.”

The works are extremely varied, not only in tone and in medium, but also in the political realities to which they’re responding. If there’s a showstopper, it’s South African artist Haroon Gunn Salie’s installation “Senzenina” (2018) on the third floor, which memorializes the 34 striking platinum miners killed in 2012’s Marikana massacre. The crouching, headless figures of the dead, rendered entirely in black, form a powerful elegy that also speaks to crackdowns on peaceful protesters and organizing laborers the world over. A rumbling, abstract soundtrack combining audio of the protests and police shootings adds a visceral dimension to the ominous group of figures. A much more modest yet just as evocative drive to commemorate the oppressed is at play in Peruvian sculptor Daniela Ortiz’s six small ceramic works, which imagine alternative civic monuments to slain activists and the systemically oppressed, including one of a beheaded Christopher Columbus.

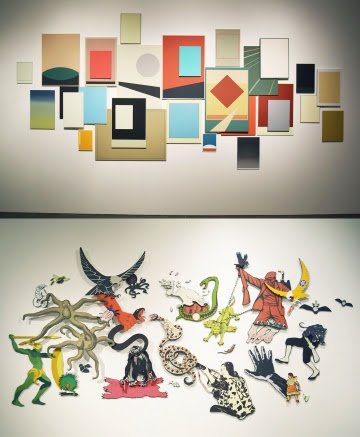

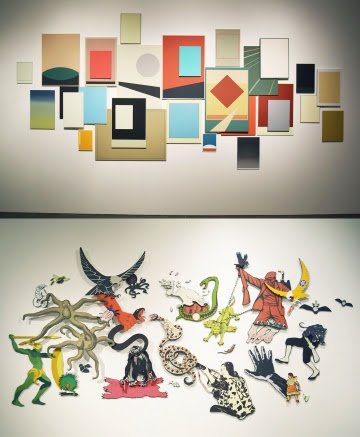

Both sides of Claudia Martínez Garay’s diptych installed on opposing walls, “Cannon Fodder / Cheering Crowds” (2018), acrylic on wood (click to enlarge)

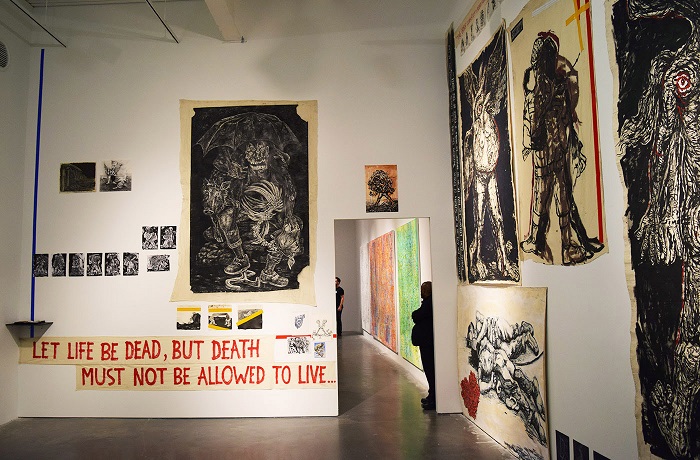

Many of the political statements in Songs for Sabotage are articulated in unexpected materials, and often delivered with a healthful dose of humor. The British artist of Sikh descent Hardeep Pandhal, for instance, raps on the soundtrack of his raucous and grotesque digital animation “Pool Party Pilot Episode” (2018), which pans across a post-apocalyptic cityscape covered in racist and sexist graffiti. The textile works of Russian artist Zhenya Machneva poke fun, more or less gently, at the aesthetics of Socialist Realism and its monuments. In her diptych “Cannon Fodder / Cheering Crowds” (2018), the Peruvian artist Claudia Martínez Garay has abstracted the geometric forms and color schemes of political posters and leaflets into an approximation of Minimalist paintings on one wall. On the facing wall, an array of human and animal symbols representing groups that fought in various armed conflicts — the snakes of the Axis powers in World War II, a bald eagle for the US, a Black Panther for the revolutionary group of the same name — are engaged in a bloody battle royale.

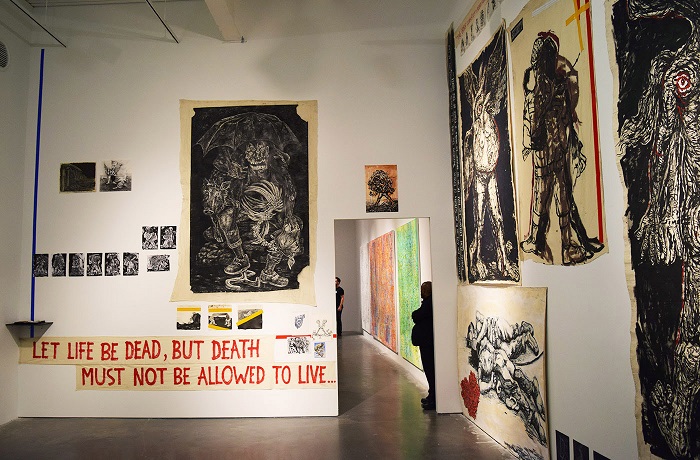

Installation view of the fourth floor of Songs for Sabotage

There are plenty of surprising and memorable works here, and mercifully few that make almost no impression at all — though US artist Diamond Stingily’s modified swing set and Norwegian sculptor Tiril Hasselknippe’s suspended steel forms combine to make the fourth floor the exhibition’s weakest. But even there, the series of shimmering bas-relief works that Philadelphia-based artist Wilmer Wilson IV made with thousands of staples arranged in undulating patterns are worthwhile, as are adjacent paintings by the Zimbabwean artist Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude and a hypnotic video by the Greek artist Manolis D. Lemos.

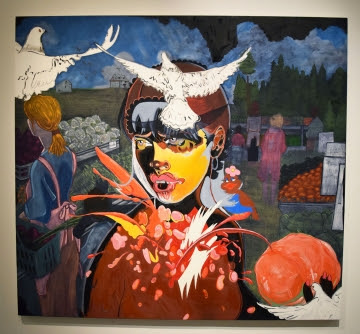

Janiva Ellis, “Curb Check Regular, Black Chick” (2018), oil on canvas

The theme of global political awareness and resistance is broad and, as with the recent Trigger exhibition at the New Museum, Songs for Sabotage feels a little lacking in internal coherence. Still, some of its most memorable works are also its least blatantly political. In addition to Machneva’s deadpan textiles riffing on Soviet Realism, Ortiz’s ceramic proposals for statues to the oppressed, and California artist Janiva Ellis’s uncomfortably superb paintings depicting black pain, a personal favorite that ostensibly has nothing to do with politics is Hong Kong artist Wong Ping’s 13-minute animation “Wong Ping’s Fables 1” (2018).

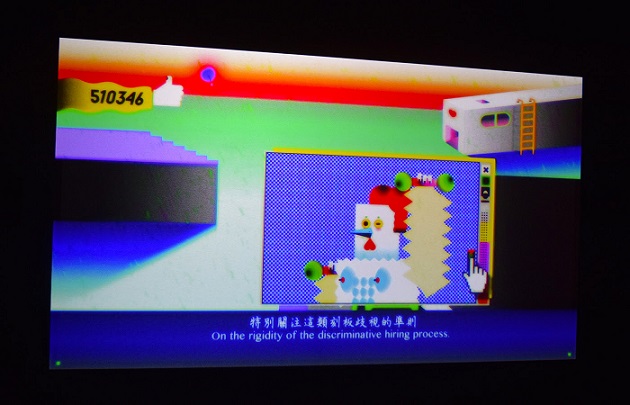

In three interconnected vignettes, Wong follows animal and plant characters through more-or-less mundane activities: a turtle and elephant who used to date meet at a diner; a chicken uses viral video fame to land a high-profile law enforcement job; and an anxious tree rides the bus. The short’s palette of bold primary colors and stylized aesthetic — retro 8-bit shot through with social media emoji — contrast sharply with the very adult situations faced by its cartoon characters. Each of the three fables is punctuated with an absurd, deadpan moral; the last reads: “To all righteous thinkers, perhaps it is worthwhile to spend more time considering how meaningless and powerless you are.” Like the most resonant works in Songs for Sabotage, Ping’s irreverent fables acknowledge the hardships of those who are powerless and the much greater dangers faced by those who refuse to remain so.

Still from Wong Ping, “Wong Ping’s Fables 1” (2018), single-channel animation, sound, color, 13 minutes

Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude, “The New Zimbabwe” (2018), oil on canvas

Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude, “The New Zimbabwe” (2018), oil on canvas

Installation view of Songs for Sabotage

Installation view of Songs for Sabotage

Wilmer Wilson, “ELEVEN” (2017, detail), staples and pigment print on wood

Wilmer Wilson, “ELEVEN” (2017, detail), staples and pigment print on wood

Lydia Ourahmane, “Finitude” (2018), ash, chalk, steel, and looped sound

Lydia Ourahmane, “Finitude” (2018), ash, chalk, steel, and looped sound

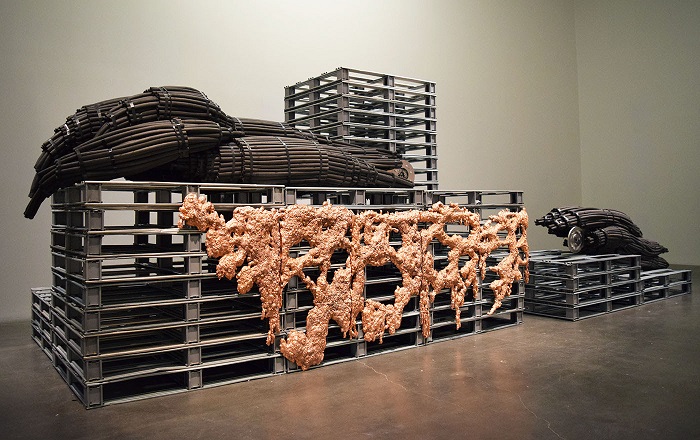

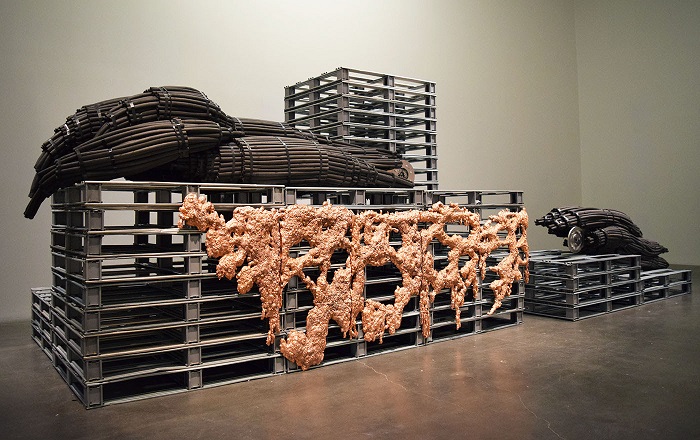

KERNEL (Pegy Zali, Petros Moris, and Theodoros Giannakis), “As you said, things resist and things are resistant” (2018), mixed media installation with aluminum pallets, copper-plated acrylic resin, foam cable-jackets, steel, and robotic mechanism

KERNEL (Pegy Zali, Petros Moris, and Theodoros Giannakis), “As you said, things resist and things are resistant” (2018), mixed media installation with aluminum pallets, copper-plated acrylic resin, foam cable-jackets, steel, and robotic mechanism

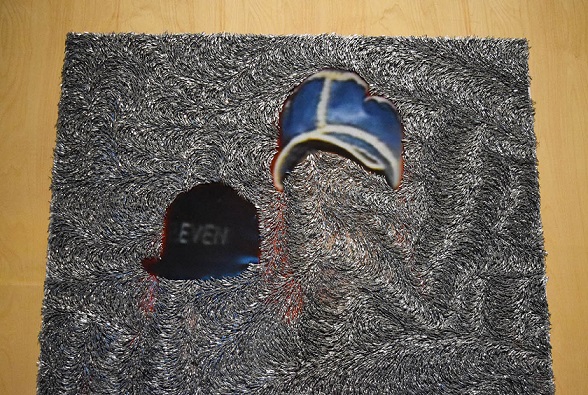

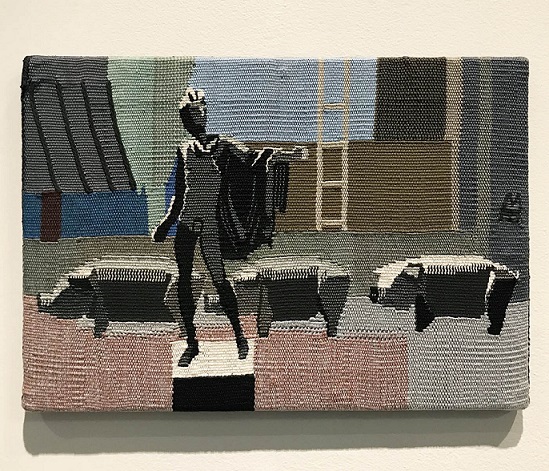

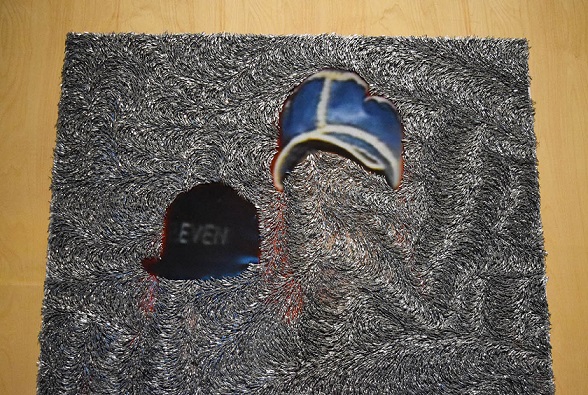

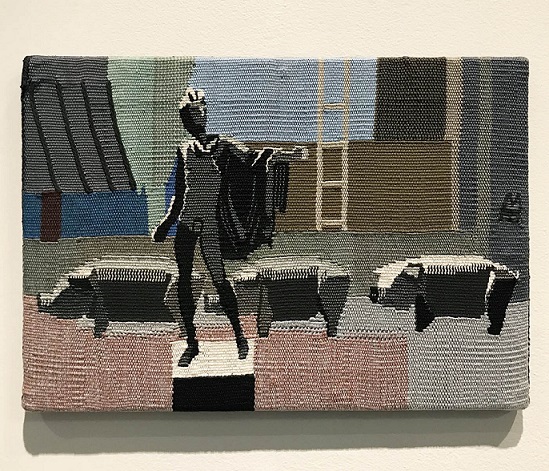

Textile works by Zhenya Machneva

Zhenya Machneva, “Project: Edition 1/1 ‘Apollo and pigs'” (2015), cotton, linen, and synthetics

Clan Dayrit, “Mapa de lo que ahora se como Las Islas Pilipinas” (2017), mixed mediums

Clan Dayrit, “Mapa de lo que ahora se como Las Islas Pilipinas” (2017), mixed mediums

Violet Dennison, “M.O.O.P.” (2018),seagrass collected in the Florida Keys, resin, and electrical metallic tubing conduit

Violet Dennison, “M.O.O.P.” (2018),seagrass collected in the Florida Keys, resin, and electrical metallic tubing conduit

Paintings by Chemu Ng’ok

Paintings by Chemu Ng’ok

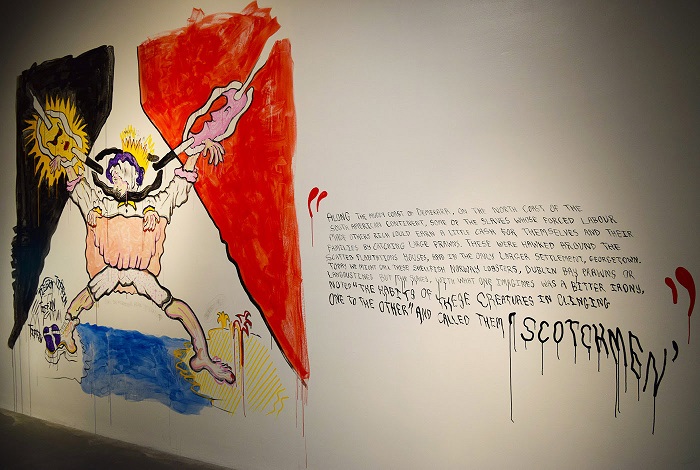

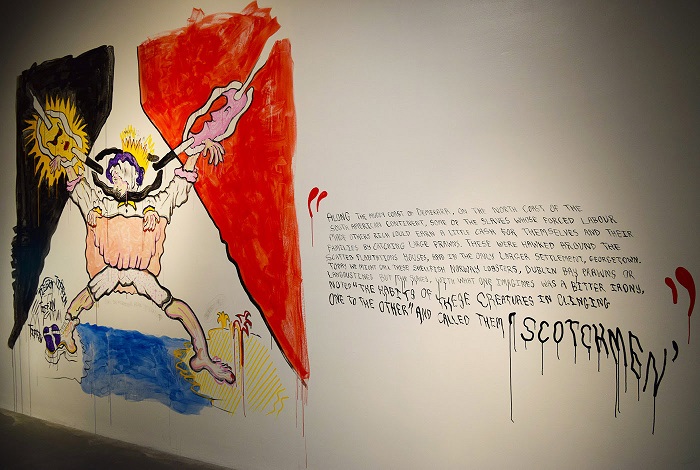

Hardeep Pandhal, “Black by Day, Red by Night (Mood Board)” (2018), spray paint, enamel, lead, and graffiti marker

Hardeep Pandhal, “Black by Day, Red by Night (Mood Board)” (2018), spray paint, enamel, lead, and graffiti marker

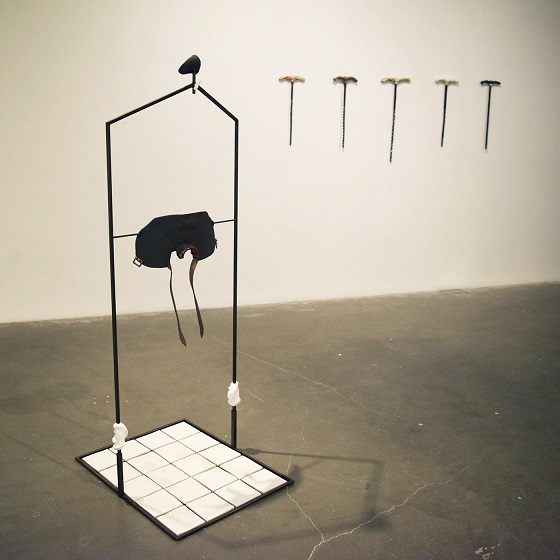

Works by Julia Phillips

Installation view of Songs for Sabotage with sculptures by Matthew Angelo Harrison in the foreground and paintings by Janiva Ellis in the bac

Installation view of Songs for Sabotage with sculptures by Matthew Angelo Harrison in the foreground and paintings by Janiva Ellis in the bac

Detail of Matthew Angelo Harrison, “Prototype of Dark Silhouettes” (2018), sculptures from West Africa, polyurethane resin, anodized aluminum, automotive clay, and zebra bone

Detail of Matthew Angelo Harrison, “Prototype of Dark Silhouettes” (2018), sculptures from West Africa, polyurethane resin, anodized aluminum, automotive clay, and zebra bone

Manuel Solano, “I Don’t Know Love” (2017), acrylic on canvas

Manuel Solano, “I Don’t Know Love” (2017), acrylic on canvas

Dalton Paula, “Enfia a faca na bananeira” (2017), oil and silver foil on canvas

Works by Daniela Ortiz

Works by Daniela Ortiz

Works by Tomm El-Saieh

Works by Tomm El-Saieh

Installation view of Anupam Roy, “Surfaces of the Irreal” (2018), mixed mediums

Installation view of Anupam Roy, “Surfaces of the Irreal” (2018), mixed mediums

Detail of Anupam Roy, “Surfaces of the Irreal” (2018), mixed mediums

Detail of Anupam Roy, “Surfaces of the Irreal” (2018), mixed mediums

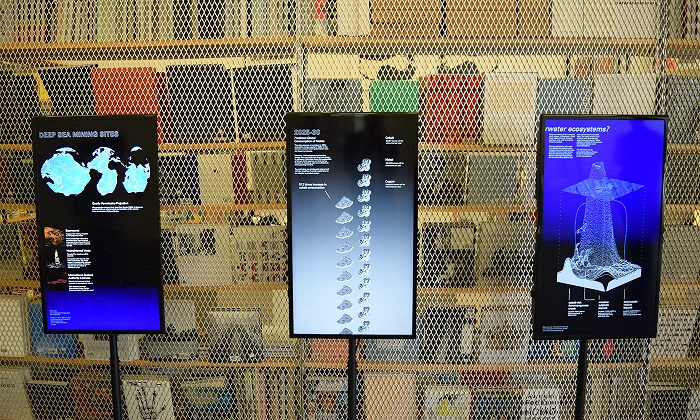

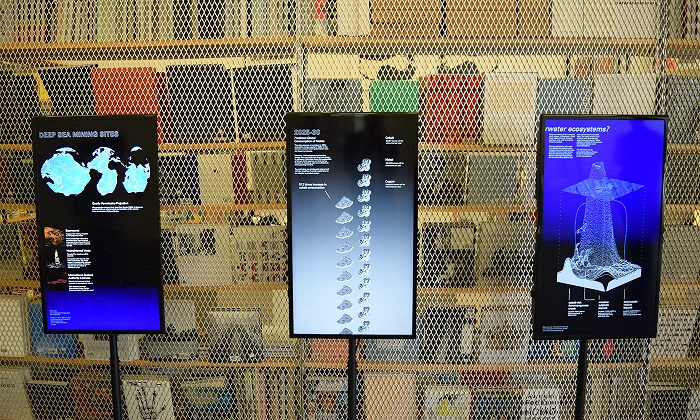

Inhabitants with Margarida Mendes, “What Is Deep Sea Mining? Graphics for a Campaign” (2018), looped digital animations; data visualization by Philippe Rivière and animations by Herma Films

Inhabitants with Margarida Mendes, “What Is Deep Sea Mining? Graphics for a Campaign” (2018), looped digital animations; data visualization by Philippe Rivière and animations by Herma Films