Like many African American portraitists, Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley represent the Obamas as themselves, and as more than themselves.

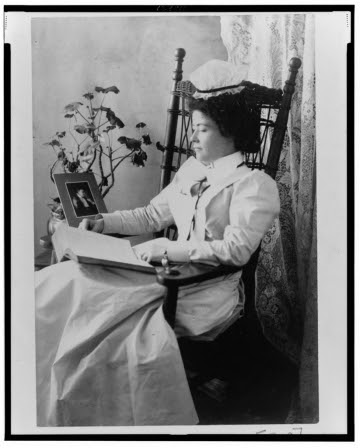

At left, a photograph by Thomas E. Askew of women sitting on the steps of Atlanta University, from an album prepared by W.E.B. Du Bois (c.1899, via Library of Congress); at right, Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama (2018, ©Amy Sherald, courtesy National Portrait Gallery)

On February 12, the presidential portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama were unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. Much of the commentary on the works, by African American artists Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, has centered on questions of likeness. But such debates miss an essential point: these pictures represent the former first couple both as individuals and as archetypes of African Americans. Sherald and Wiley’s portraits are the newest additions to a long history of black representation, rooted in photography, that aimed to expand what blackness could be in America. These paintings also expand what presidential portraits can be.

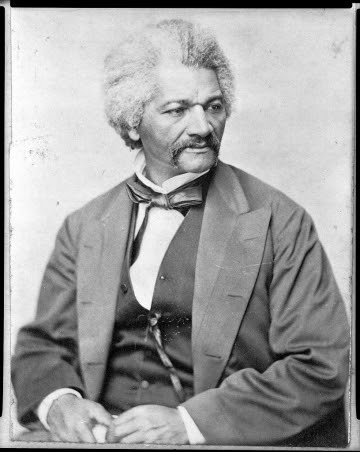

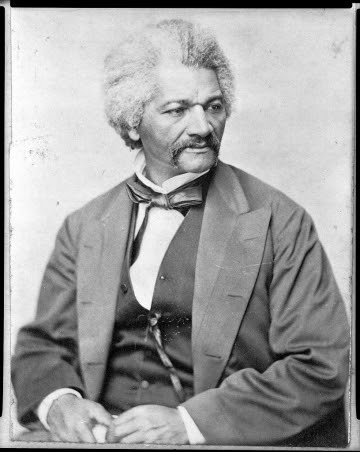

Since the invention of the daguerreotype, in 1839, African Americans have used photography as a means of representing themselves against the backdrop of negative imagery, which often attempted to rob us of our humanity. Frederick Douglass, said to have been the most frequently photographed American of the 19th century, saw photography as a means to chart black progress from slavery, and to upend white stereotypes of black people.

A photograph of Frederick Douglass from 1870, taken by George Francis Schreiber (via Library of Congress)

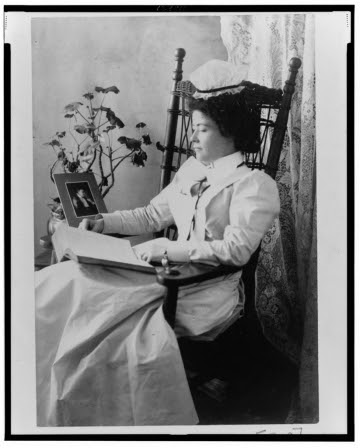

Similarly, at the turn of the 20th century, photography became a key tool to foreground images of African Americans as educated and successful. For the American Negroexhibition at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition, W.E.B. Du Bois assembled 500 photographs, 72 charts and diagrams, and over 200 books written by African American authors to show the state of black America at the time. The numerous portraits featured black men, women, and children in the current fashions of the day. Their poses reflected the portraiture styles of the day; their suits, elaborate dresses, and starched collars, and pocket watches exude affluence. Posed with their military decorations, a book, or seated around the organ at Fisk University, their accoutrements frame the subjects as intelligent and sensitive people.

A photograph of a nursing student taken by Thomas E. Askew and compiled by W.E.B. Du Bois (c.1899, via Library of Congress)

That same year, Booker T. Washington published A New Negro for a New Century: An Accurate and Up-to-Date Record of the Upward Struggles of the Negro Race. This 428-page book contains 60 elegant photographic portraits of white-collar African American men and women. Among them were Washington; Douglass; Du Bois; the educator and women’s rights activist Fannie Barrier Williams; and the poet, novelist, and playwright Paul Laurence Dunbar. Most of the book’s portraits are headshots in which the sitters, in their finest clothing, adopt dignified poses that suggest an air of confidence and accomplishment. These portraits, like the images from the 1900 Paris Exposition, show sitters at their very best.

“Evening Attire,” James Van Der Zee (1922, via Wikimedia Commons)

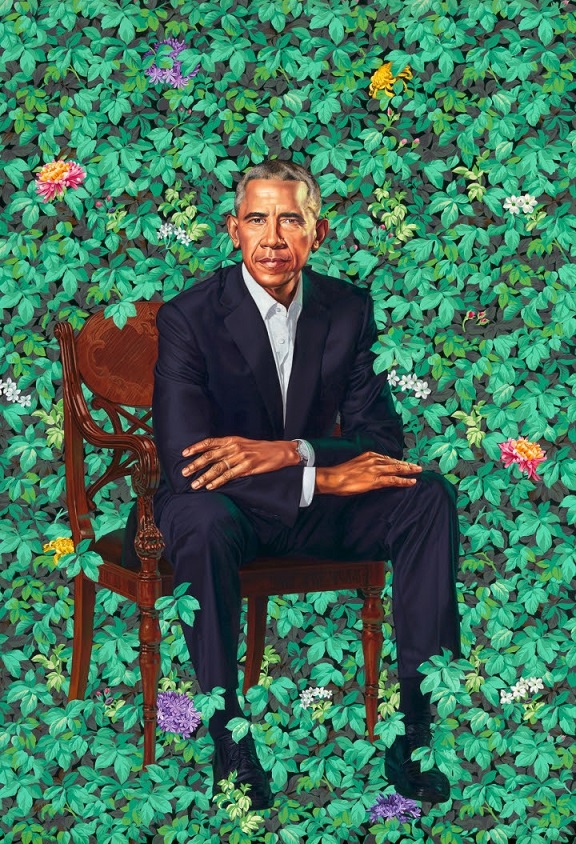

The Obama portraits, though not directly related to the historical photographs, fit into this tradition of images aimed at lifting up a race. Douglass, Du Bois, and Washington understood what many black people know: images of African Americans detail individuals, but they can also be interpreted as depictions of African Americans in general. As such, images of Douglass, photographs collected by Du Bois, and Washington’s book of prose and portraits aimed to exemplify unassailable black progress: black success in a society that, at every turn, denied African Americans full personhood. These men hoped that their images — these black archetypes — would not only disarm racist stereotypes but also bolster black self-esteem.

Since that time, countless African American artists have used portraiture — in photographs and paint — to explore the complex nature of their subjects, as well as black life. Many have focused on the bodies and the style of their sitters, from photographer James Van Der Zee’s portraits from Harlem, to the paintings of William H. Johnson, to the contemporary work of Awol Erizku, Barkley L. Hendricks, and Mickalene Thomas. Van Der Zee’s impeccably-dressed figures, Hendricks’s slick men, and Thomas’s ultra-chic women celebrate blackness, while also insisting that we see black people differently than they see others.

A painting by Mickalene Thomas (via Flickr user libby rosof)

Viewers often assume that painted portraits emerge from the imagination of the artist, while photographic portraits come from a transparent, documentary transcription of life. But the above examples show the artistry and intention involved in all kinds of portrait-making, whatever the medium. Portraits, whether photographic or painted, aim to reveal something about the sitter. Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley’s portraits of the former first couple fit comfortably into this tradition.

Sherald used grisalle, a technique of painting in gray monotones, to depict Michelle Obama’s skin, and her portrait channels the history of positive black representation made possible through photography. The former first lady’s pose, and the painting’s composition, seem to nod to the studio portraits of Malian photographer Seydou Keïta. The flowing Michelle Smith dress that accentuates her body also recalls the renowned quilts of Gee’s Bend and the abstract canvases of Piet Mondrian, as if to blend black vernacular culture with modernist painting. Sherald’s portrait is a slow burn: we have to spend time with it. Our reward for doing so is a new insight into Michelle Obama’s psychological depth, and a reminder of her position as a powerful and graceful woman, as comfortable delivering official remarks as she is dancing with a two-year-old she just met.

Visitors gather around studio portraits by the Malian photographer Seydou Keïta at the Grand Palais in Paris (via Flickr user Jean-Pierre Dalbéra)

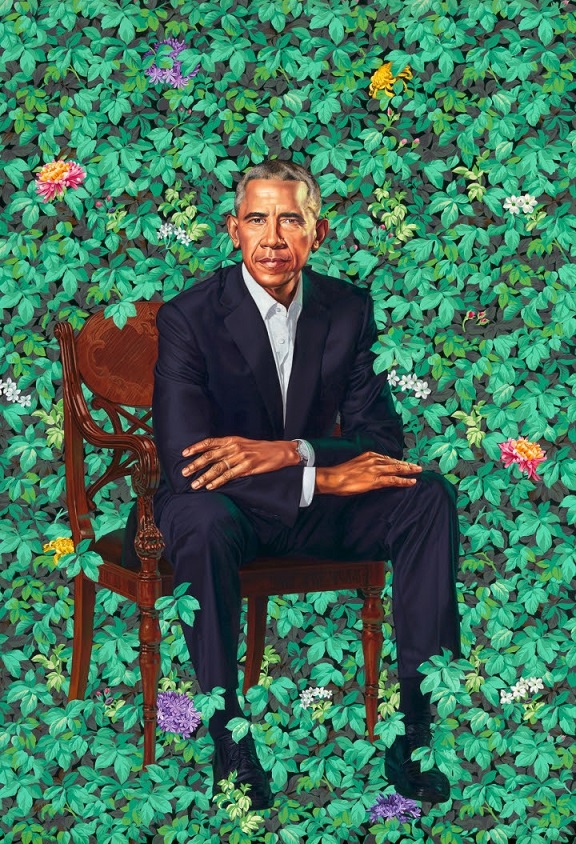

Wiley paints Barack Obama differently. He often riffs on epic stories, of the sort you might see in a monumental Baroque painting. In his 2005 canvas “Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps,” the artist replaced the leader with a young black man. In his 2012 painting “Judith Beheading Holofernes“(one of multiple versions of the subject he has painted), he recasts the main subject as a black woman. His portrait of Barack Obama, which takes up similar concerns, is at once an abstract reflection on power and the presidency, and also a personal image of the man himself. Obama sits against one of Wiley’s trademark foliate backgrounds, but these particular flowers allude to the former president’s biography. The white jasmine blossoms recalls the Hawai’i of the President’s birth. The purple African lilies represent his Kenyan heritage. The chrysanthemums symbolize Chicago, where the President’s professional and political career took root. Obama’s pose and clothing suggest a generic cool, but the lines on his face and the sensitive rendering of his hands bring our attention back to this body, this man.

Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama (2018, ©Kehinde Wiley, courtesy National Portrait Gallery)

Sherald and Wiley represent the Obamas as themselves, and as more than themselves. In this sense, they are the continuation of the long history of African American portraiture: the artists and their subjects are acutely aware that the genre reveals something about the individuals depicted, and about African American culture writ large. They adopt the political challenge of disarming stereotypes that, even today, are alive and well.

At the same time, the artists used the occasion of the Obama commissions to broaden the possibilities of portraits. They offer insight to the long, complex relationship between African American painting and the history of Western art. With all of their varied references, and the connections they make to black culture and the art world, the Obama portraits teach us not only to see African Americans differently, but also to look beyond likeness and expand our ideas of portraiture.

Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama (2018, ©Amy Sherald, courtesy National Portrait Gallery)