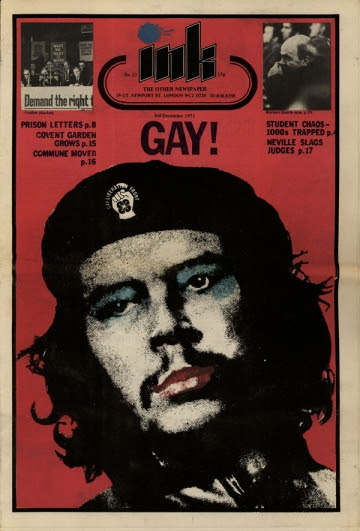

Peter Hujar, “Gay Liberation Front Poster Image” (1969), gelatin silver print, 18 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches (courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum, © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC)

The planned demolition “is a real loss that shows the significance of LGBT spaces and cultural sites in the city should be recognized,” Ken Lustbader, a co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project told Hyperallergic. “We’re trying to get ahead of the curve proactively to identify these sites that show and convey LGBT history.”

Lustbader, Jay Shockley, and Andrew Dolkart founded the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project as a nonprofit in 2014, after receiving a grant from the National Park Service —“the first ever LGBT-related grant given” by the agency, Shockley said. Their mandate was to identify and research sites that have been important historically and culturally to the LGBTQ community.

The project also nominates sites to the National Register of Historic Places, an honorary federal list that includes over 93,500 sites across the country. LGBTQ history remains seriously underrepresented, with less than 20 sites in the Register.

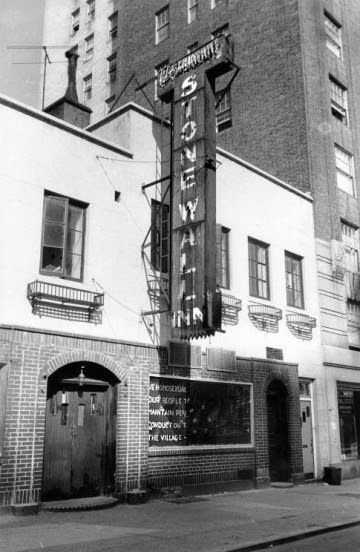

Since its inception, the Project has added five New York City sites. Earlier this year, Earl Hall at Columbia University was listed for its affiliation with the Student Homophile League, the first gay student organization in the country, founded in 1966 at Columbia University. Last year, it listed Greenwich Village’s Caffe Cino, and it amended the nomination to the Alice Austen Houseon Staten Island, which had been “written in the 1970s but needed to be amended to update her same-sex relationship and add more information about her pioneering transgressive photography.” Julius Bar and the Bayard Rustin Residence were added in 2016. (Stonewall was added to the registry in 1999, with help from Shockley and Dolkart.)

The Stonewall Inn as it appeared during Pride Week 2016 (via Wikimedia)

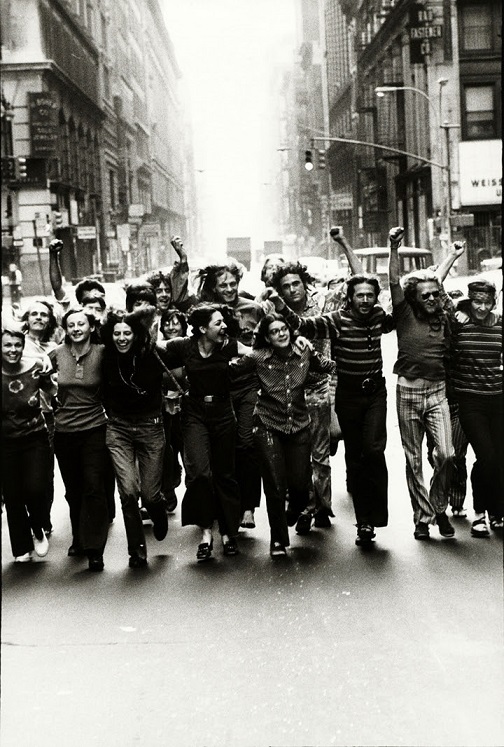

This is first time in the four-year history of the organization that a site is actively being threatened with demolition. The threat of losing such an important piece of queer history underscores the urgency of the organization’s work: to document neglected, forgotten, and vanishing sites that shaped LGBTQ communities and American culture.

This year, the Project partnered with New York City’s Historic District Council (HDC) in Six to Celebrate, an effort to “identify sites in the city that are significant related to cultural heritage.” The importance of this site, where GLF organized resistance to the persecution of LGBTQ communities, “cannot be overstated,” Shockley said.

The cover of Ink, an alternative newspaper that covered the GLF in 1971 (via Wikimedia)

For the organization’s founders, the importance of national history is matched by an awareness of local transformation. Lustbader and Shockley live blocks away from the GLF’s former meeting site. “There’s been increasing discussion over the last year about all new developments on 14th Street,” Shockley said, describing another planned demolition at an adjacent site. The 1952 building where Banksy recently drew his now-famous rat sold last year, for $42.4 million, is set to be torn down to make room for a condominium and retail space. That building also had a 110-foot-long mural in its lobby: Julien Binford’s “A Memory of 14th Street and 6th Avenue.” If it weren’t for the joint efforts of New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and the community-based preservation group Save Chelsea, that too, would’ve been destroyed forever. “14th Street, like every place else in Manhattan, is getting attacked by high rise development,” Shockley said.

There are currently 118 sites on the NYC LGBT Sites website. 400 have been nominated by the public and are currently in the project’s database. The process of researching and factually checking data is lengthy: “photographic documentation, multi-media, interviews,” said Lustbader. “We don’t want information that isn’t fully vetted.” Once they are satisfied with the factual accuracy, they make specific sites public “based on some priorities that include rarity, timing with anniversaries, and significance.”

As the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots approaches, the Project’s goal is to expand the research to past Manhattan, and to adapt their research for use in classrooms. Two more nominations to the National Register of Historic Places are also in the works, but their names can’t be announced yet, since consent from the property owners is needed. The organization is also working to secure “individual landmark” status for the Walt Whitman Residence in Brooklyn.