LOS ANGELES — The word “curator” has become so ubiquitous as to be essentially meaningless, comprising everything from a custodian of objects and artifacts at a museum, to someone who merely selects things, be those internet memes, corporate brands, or songs for a digital playlist. The Getty Research Institute’s exhibition Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions brings some gravitas back to the title, perhaps ironically, by showcasing the work of the groundbreaking Swiss curator whose intellectual scope extended well beyond the confines of the contemporary art world.

Born in 1933, Szeemann became the youngest museum director in the world when he assumed the directorship of the Kunsthalle Bern at the age of 28 in 1961. He put the institution on the international map with a series of exhibitions that not only showcased then-underground movements in contemporary art, but also focused on art of the mentally ill, religious folk art, and science fiction. He left the Kunsthalle in 1969, becoming what some consider to be the first “independent curator,” traveling the world and creating over 200 exhibitions throughout his career. He essentially created the model of the globe-trotting celebrity curator of which Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach are perhaps the most recognizable heirs (for better or for worse). Driven by a boundless intellectual curiosity, Szeemann’s exhibitions challenged historical narratives and exploded aesthetic hierarchies, expanding the role of curator from simply a steward of objects to a shaper of ideas.

Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions at the Getty Research Institute (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

The Getty exhibition originated in the museum’s acquisition of Szeemann’s archives — which he dubbed the “Museum of Obsessions” — in 2011. It was the largest collection ever acquired by the Getty Research Institute, including 28,000 books, 36,000 photos, and over 1,000 boxes of ephemera, drawings, letters, and notes. Exhibition curators Glenn Phillips and Philipp Kaiser have done an impressive job of paring down from this massive trove of material, choosing to focus on a few seminal exhibitions as opposed to attempting to cover Szeemann’s five-decade career in full. It is divided into three sections: “Avant-Gardes,” focused on his seminal exhibitions of contemporary art of the ’60s and ’70s; “Utopias and Visionaries,” which explores exhibitions about early 20th-century utopias, modernists, and mystics; and “Geographies,” examining his Swiss identity and peripatetic later career. This was a wise choice, presenting an exhibition that is both didactic and dynamic without feeling overwhelming, and leaving room for further exploration.

James Lee Byars in the section on Documenta 5, in Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions at the Getty Research Institute

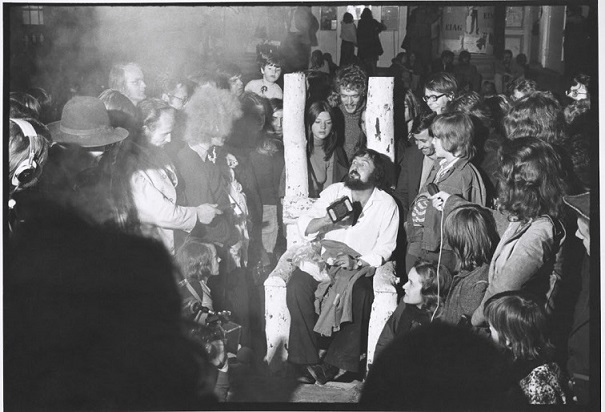

The “Avant-Gardes” section begins with his most famous exhibition, 1968’s When Attitudes Become Form, which featured new trends in conceptual and minimalist art. For the show, Richard Serra flung 460 pounds of molten lead against the walls, while Lawrence Weiner removed a section of the wall, and Michael Heizer smashed the street in front of the museum with a wrecking ball. The controversial exhibition garnered the young curator international recognition — and also led to his resignation from the Kunsthalle.

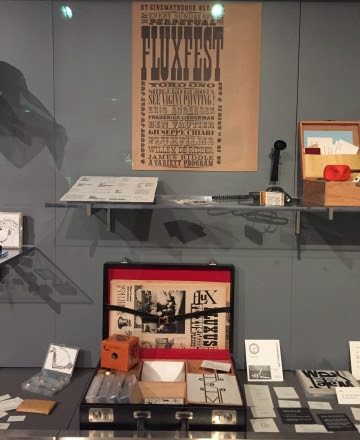

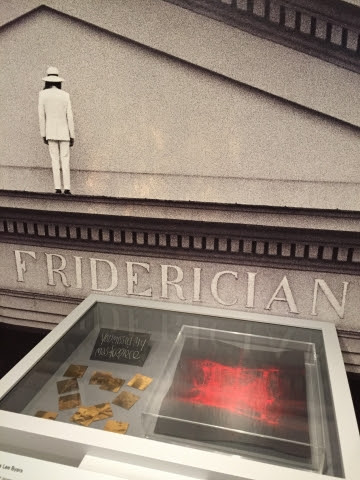

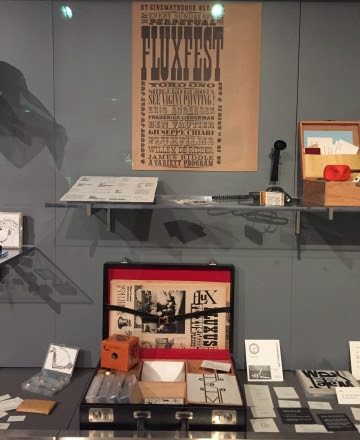

Also highlighted are shows on Fluxus (1970), and Documenta 5 (1972), the major international art quinquennial held in Kassel, Germany. Of particular note is the spotlight on James Lee Byars, the whimsical, idiosyncratic artist who stood on the roof of the Fridericianum, calling out common German names through a megaphone at the opening. Also included are his humorous telegrams to world figures including Mao and Nixon, inviting them to Documenta. Instead of attempting the Sisyphean task of recreating these monumental exhibitions in full, the curators at the Getty do their best to offer glimpses of what they were like and their significance through photographs, drawings, notes, posters, and correspondence.

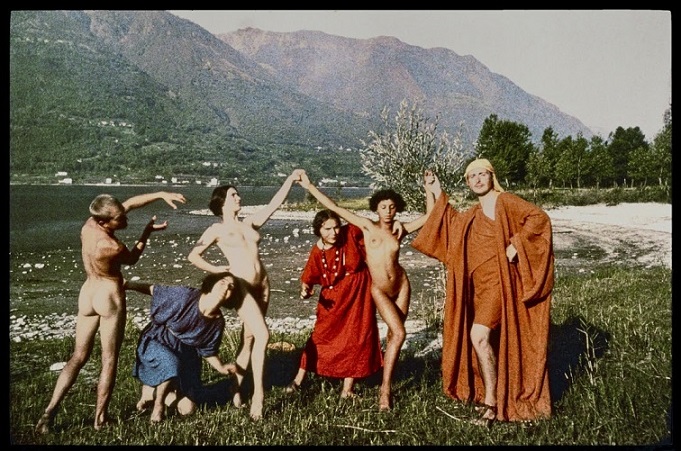

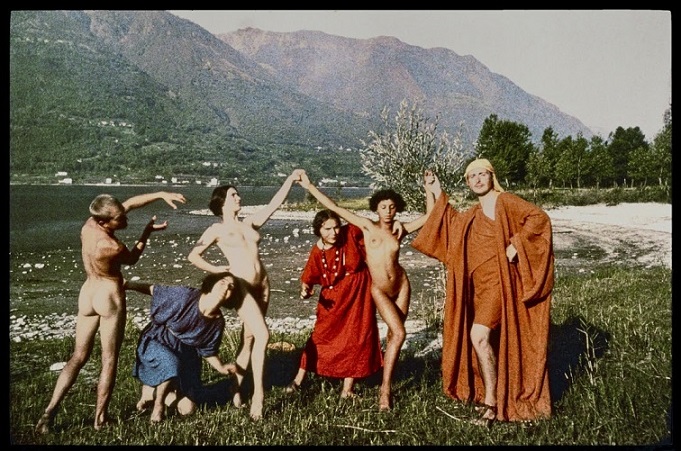

The following sections of Museum of Obsessions showcase Szeemann’s cross-pollination between the worlds of high art and everyday material culture that would characterize his legacy, zig-zagging between iconic works like Duchamp’s “Boîte-en-valise,” and photos of nude Swiss utopians frolicking in a bucolic landscape, taken from Szeemann’s intimate exhibition on the little-known Swiss commune Monte Verità.

From left, dancers Totimo, Suzanne Perrottet, Katja Wulff, Maja Lederer, Betty Baaron Samoa, and

Rudolf von Laban at Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland, 1914. (the Getty Research Institute, photo by Johann Adam Meisenbach, courtesy of Meinhard Meisenbach)

If Museum of Obsessions can only offer rough sketches and highlights of his career, a just-closed exhibition across town took a deeper dive into one of his more unusual and deeply personal endeavors. Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us at the ICA LA was a meticulous recreation of Szeemann’s 1974 exhibition, which painted a portrait of the curator’s grandfather, Etienne, a successful hairdresser, through objects, letters, and photos. In the center of their warehouse-like exhibition space, the ICA built a series of rooms and passageways which guided the viewer through the various stages of his life, concluding with a recreation of his home and salon.

Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us at the ICA LA

The exhibition did not make the case for Etienne as an extraordinary individual. Rather, it was a testament to the power that objects have to tell stories and impart meaning to our lives. Upon returning home, we are likely to view the material culture of our everyday life — our spoons, books, linens, and family photos — with fresh eyes.

As radical as Szeemann was in exploding the idea of what an exhibition could be, in other ways he was quite traditional. Disappointingly, but perhaps not unsurprisingly, women and artists of color do not feature prominently in his oeuvre. In one sense, he opened up the cloistered museum to all sorts of new ideas and objects, but in another he created the template for the globe-trotting aesthete who travels from biennial to biennial, operating in a rarified and isolated plane. If there is one thing we can glean from his legacy, it is that his radical curiosity and genre-defying practice can and should be applied to many other parts of our art world.

Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us at the ICA LA

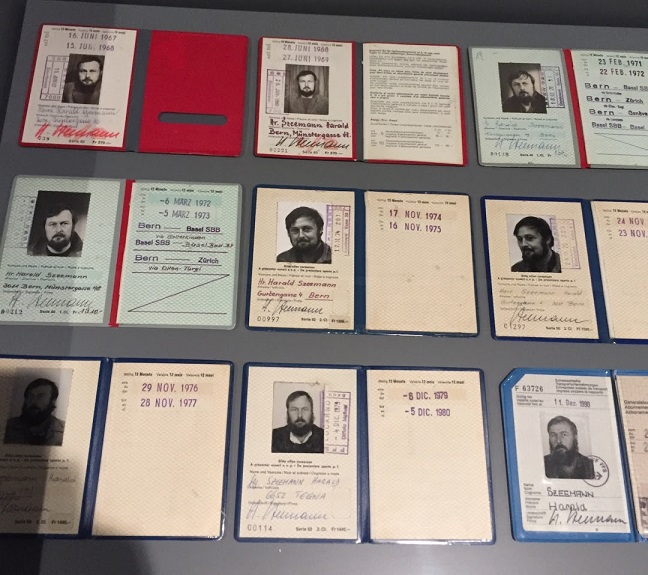

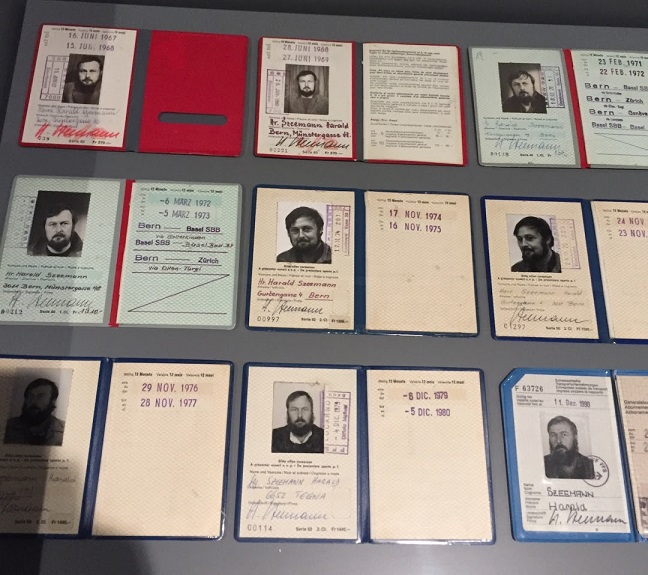

A few of Szeemann’s many passports in Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions

Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions continues at the Getty Research Institute (1200 Getty Center Dr #1100, Los Angeles) through May 6.

저도 지난 달에 LA에서 이 전시를 보았습니다만 한 사람이 세상을 바꾸어 놓을 수 있다는 점에서 다 같이 만드는 교육이 아니라 남과 다른 교육 그리고 내버려두는 교육이 필요하다는 생각을 해 보았습니다.