The Baltimore Museum of Art will deepen its holdings of works by women and artists of color using funds from sales of seven redundant works.

The Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mike Steele, via Flickr)

BALTIMORE — “A museum is a place where racism and sexism is on full display,” said artist Shinique Smith. “You can see this in any institution in any part of the world.” Smith, an internationally known painter and sculptor based in New York and Los Angeles, who has works in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Rubell Collection, the Whitney Museum, and numerous others, grew up in Baltimore and recalled the profound influence of the Baltimore Museum of Art on her development as an artist. “When I grew up, there was no contemporary wing at the BMA, so I grew up looking at Henri Matisse and Romare Bearden there.” When she grew older and became a student at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), she recalled seeing Robert Rauschenberg’s “Canyon” at the BMA as a primary influence over her own abstract and bundled fiber works.

These recollections were part of a series of conversations I had recently with artists, curators, and museum professionals, after the Baltimore Museum of Art announced last month that it would be diversifying its collection to enhance visitor experience through recent acquisitions of works by women and artists of color and by deaccessioning repetitive works. The announcement read:

The funds raised will be used exclusively for the acquisition of works created from 1943 or later, allowing the museum to strengthen and fill gaps within its collection. During the same meeting, the trustees approved the acquisition of nine works by contemporary artists Mark Bradford, Zanele Muholi, Trevor Paglen, John T. Scott, Sara VanDerBeek, and Jack Whitten, several of which are the first by the artist to enter the collection.

The seven works marked for deaccession will be sold at auction or in private sales. They include a Franz Kline, two by Kenneth Noland, a Jules Olitski, a Rauschenberg, and two pieces by Andy Warhol. The museum said that it has followed the guidelines established by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD).

“These men that we are talking about deaccessioning, I looked at them growing up because I had to,” Smith recalled. “In terms of growing up in the art world, I had to do extra research beyond the museum to find artists of color. This move is a correction and, for the demographics in Baltimore, it makes sense. The museum should be for everybody and should reflect the diversity of Baltimore.”

I agree with Smith. When I read the release, I thought very little about it initially because our cultural institutions, especially museums, are obviously lagging in their missions to present and collect the most significant works of art of our time. Why wouldn’t you sell off redundant works, deemed to be lesser in value than similar works in the museum holdings, in order to buy others by underrepresented contemporary artists?

Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017 installation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood, courtesy the Baltimore Museum of Art)

Smith’s statement reinforced my own experiences with the BMA over the past 20 years. Until this past year, the museum had hosted just one major, ticketed exhibition with a catalogue devoted to a woman or an artist of color — Joyce J. Scott: Kickin’ it with the Old Masters in 2000. In a city that is more than 60% African American, the news that the museum will sell redundant works by white men to purchase new works by women and artists of color is a no-brainer. For me, the more interesting story is a broader move by the museum, which has embraced a number of artists of color in the past year, hosting exhibits by Senga Negudi, Meleko Megosi, Al Loving, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Stephen Towns, and a Jack Whitten exhibition that will travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with an Amy Sherald exhibition in the works for 2020. However, the news quickly ignited controversy and sparked discussions of widespread changes in museum culture that should be, in my view, ubiquitous.

* * *

After a Baltimore Sun article that explicitly linked the upcoming sale of art by white men with the purchase of works by women and people of color, some critics took it further, likening the practice to historical affirmative action at its worst. In a Baltimore Sun op-ed, David Maril, president of the Herman Maril Foundation and the artist’s son, wrote:

The use of deaccession — selling seven paintings to achieve this goal of supporting local and regional contemporary art — is a horrendous decision. What is especially troubling is the somewhat jubilant and self-righteous tone surrounding what the museum is doing. Never mind the positive a spin the BMA puts on this decision such as insisting it’s conducting routine museum business. Nothing could be further from reality.

Tyler Green, the producer and host of the Modern Art Notes Podcast, tweeted his concern that the BMA was not following AAM guidelines regarding deaccessioning, writing: “It’s by a man, so we’ll sell it even tho it’s a great artwork.” A subsequent tweet read: “I’d like to know where in AAM’s guidelines it says that deaccessioning motivated by gender is a best or even sanctioned practice.” Though the BMA’s press release announcing the deaccessioning doesn’t offer much insight into the process that led to the selection of the seven works to be sold, neither it nor the Baltimore Sun‘s report suggests that the motivation was the artists’ gender. Museum staff “discovered areas of repetition” in the collection, the BMA announcement states, and “in each case, the museum currently holds stronger works by the same artist, and in some cases, more significant versions from the same series or stage of the artist’s career.”

Stephen Towns: Rumination and a Reckoning installation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood, courtesy the Baltimore Museum of Art)

“Deaccessions are often controversial, but the changes they bring can be good,” said Taína Caragol, curator of Latino art and history at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. “The Baltimore Sun reported that the BMA has 90 works by Andy Warhol, two dozen by Rauschenberg, and about a dozen by Kline. The museum’s leadership has studied the issue carefully for a year and a consensus has been reached with the staff and community members that allows for more, valued artists to have a place in their collection. As curators and museum professionals, we have to keep questioning the canon, and with this let it evolve and welcome new voices. We want to see new artworks by both historic and new artists who should be better known. Deaccessioning these works creates space and raises funds for unseen artworks, without diminishing the BMA’s collection of postwar art.”

Smith concurred. “There is so much involved in how museums acquire works,” she said. “Over the past few decades, most of the people on acquisitions committees have been wealthy white people who might not be versed in works by people of color or women. The museums reflected the art world and this is a progressive move that takes us in a more historically accurate direction.” She applauded the announcement, adding that it seems directly tied to new leadership, namely the museum’s new director, Christopher Bedford, who started in September 2016.

Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963–2017 installation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

“Our commitment to achieving equity and historical accuracy in the way we narrate the history of postwar art has been made manifest from the first acquisitions we made after I assumed the directorship of the BMA,” said Bedford. “Mark Bradford, Sharon Lockhart, Norman Lewis, John Scott, Wangechi Mutu, Jack Whitten, Zanele Muholi, Jeff Donaldson — to name only a few purchases made in the last 15 months.”

One curator I spoke to, who refused to be named for this story, questioned the relationship between the sales of the seven works and the way the funds raised would be used in the future. Asked about the implied relationship between the upcoming auctions and whether there was an explicit guarantee that money will be spent on works by diverse artists, Bedford elaborated on how the funds will be used.

“Of the seven objects being sold, proceeds from the two Warhols will be put in a donor-mandated spend down fund, meaning that we will not treat those proceeds as an endowment,” he explained. “Rather, it is the wish of the donor to see those monies spent rapidly on a list of works we have already identified as meeting the criteria articulated above. That list was developed by a team of curators including Katy Siegel and Kristen Hileman with oversight and input from me. It is the donor’s wish that we make headway on our mission rapidly, and the condition they have placed on their support makes this inevitable.”

Bedford added that the remaining proceeds from the sales will be used to create an endowment from which the museum will draw annually to purchase postwar art. He said the fund will “substantially increase the BMA’s capacity to build its collection, making us a truly competitive force in the broader ecology of contemporary collecting.”

* * *

Thus far, the response to the BMA’s announcement, especially from curators and artists of color, has been overwhelmingly positive. “Chris Bedford is demonstrating what should happen in museums and cultural institutions in the 21st century,” according to Dr. Leslie King Hammond, former dean at MICA and a nationally known curator. “You have to be bold, be a visionary. You have to step forward and make what are sometimes misconstrued as radical decisions, when in fact it’s just addressing the overall quality, content, and intent of the institution’s role in community. He is looking at the landscape of museum culture with fresh eyes, and not repeating ubiquitous knee jerk decisions made in the past.”

Front Room: Njideka Akunyili Crosby / Counterparts installation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

“Historically, artworks by women, people of color, LGBTQ, and other marginalized people have been underrepresented in almost every art institution’s exhibitions and collection,” said Njideka Akunyili Crosby, whose solo show at the BMA, Counterparts, closed in March. “Making a commitment to acquire works by these artist demographics is a good thing, to be sure; however, the BMA’s decision to sell notable works by white men in order to fund such acquisitions is a great, radical thing — it demonstrates a deep conviction to do what it can to right a widespread historical wrong/imbalance.”

Crosby, a Nigerian and American artist who recently won a MacArthur Fellowship, added: “What’s more, this planned action amounts to an unequivocal statement that these soon-to-be-acquired works are important, that they matter. I hope other institutions follow the BMA’s exemplary decision and pursue the same goal of broader inclusivity in their collections.”

“My colleagues (past and present) and I continually think about the relationship between the contemporary and historical parts of the museum’s collection and exhibitions, and how they relate to the city of Baltimore,” said Kristen Hileman, the BMA’s Senior Contemporary Curator since 2009, who curated Crosby’s solo exhibition — a show planned years in advance of the museum’s recent series of shows by women and people of color.

Hileman said that Crosby’s show reflects a unique voice based on her life as an immigrant who married a white American and is now a mother. The works also reflect the current political climate, expressed through personal symbols including a Colin Kaepernick figurine in one of her interior scenes. Hileman said that Crosby’s paintings “help us understand the BMA’s collection better, teaching us about techniques of painting used by French artists in the Cone Collection and at the same time making us aware of the general absence of black artists, black figures, and representations of non-Eurocentric histories throughout the museum’s galleries.”

Joyce J. Scott: Kickin’ it with the Old Masters installation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (photo courtesy the Baltimore Museum of Art)

However, others expressed skepticism about the motives behind the BMA’s move, noting that there are still major gaps in inclusivity and equity among its board and staff. “It takes time and the will to admit exclusions made and the force to follow through with meaningful change,” said Joyce J. Scott, a MacArthur Fellow and lifelong Baltimore resident. “I’m sure some feel by evolving into a more inclusive realm, the prior work will be seen as less worthy, outdated, or just no good. The actual work will tell the truth.”

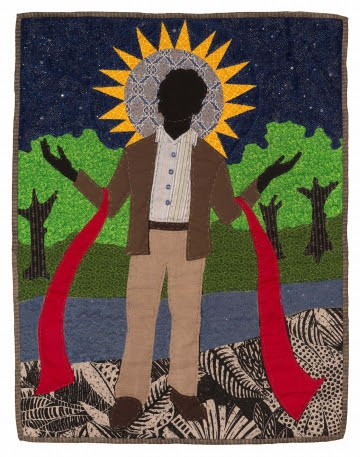

Stephen Towns, “Black Sun” (2016) (courtesy of the artist; photo by Joseph Hyde)

If we can learn anything from the overwhelming success of the recent movie Black Panther, which delivered a succinct and searing critique of hypocritical white museum culture, it’s that American audiences are hungry for diverse stories and characters. Audiences of color have been systematically kept out of mainstream culture since the inception of our country, and representation — actually seeing someone that looks like you, finally, on a big screen or museum wall — means a great deal.

For those who believe the BMA is somehow sacrificing quality for diversity, you need not look any further than the diverse roster of artists, both internationally known and based in Baltimore, that is now populating the BMA’s galleries. Bedford likened the changes to the visionary collectors whose holdings are now the BMA’s most valuable works: sisters Etta and Claribell Cone, who were early supporters of Matisse, Picasso, Degas, and others well before their works were considered valuable.

“Our desire to achieve a new relevance in the 21st century in a black majority city does not mean we are leaving our past greatness behind,” said Bedford. “Rather, we are building on the BMA’s historical investment in present-ness and contemporary art by engaging the greatest artists of the 21st century, many of whom are black Americans, to define a new golden era for the BMA. The Cone sisters did just that when they built and then donated their collection to the Museum. Building on their legacy, we are building a Cone Collection for the 21st century to ensure that we remain on the cutting edge of relevance.”

This movement may set the BMA apart from others going forward, if funds from the deaccessioning are used the way they’re supposed to be. Although her work has not been collected by the BMA, Shinique Smith still feels a strong connection to her hometown and hopes the museum will go even further in diversifying its collection.

Head Back & High: Senga Nengudi, Performance Objects (1976–2015) installation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood, courtesy the Baltimore Museum of Art)

“I was at the Museum of Modern Art a few weeks ago, happy to see the Adrian Piper retrospective,” Smith said. But when she wandered into a permanent collection gallery, she said, “my heart just fell a little. In that room, the conversation was still dominated by white men. There have always been women and artists of color who were under-recognized, and these museums own more of their works, but there were barely any up. … I know MoMa and BMA could do more and are now striving to do so.”

Dr. King Hammond takes it a step further, contending that the issue of selling works by white male artists and purchasing works by women and artists of color is an essential first step in building a culture of inclusivity and relevance at the Baltimore museum. “This is about preserving the integrity of the institution, being the protectors and stewards of the culture of our nation,” said King Hammond. “How many white males do we need? How many times can we hear the same story? Right now, so many voices are missing. They could deaccession more and make a real impact on the institution, to change how culture sees itself, full of diverse and complementary stories, but if you don’t sell the works, you don’t have the resources. It’s time to open up the playing field and get new players on the field.”