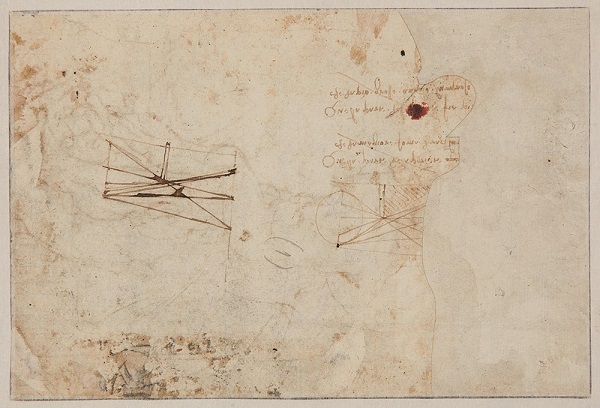

The frea, verso, side of the drawing. Photo courtesy Tajan.

It would be nice if the Tajan auction house laid all its cards on the table, publishing test results and the complete provenance. But there is no precedent for this in the art trade. The general attitude toward opacity, centuries old, remains: we are the elite experts; we have specialised knowledge that you do not; we will tell you what is genuine, and you will believe us. Consider the three steps to the authentication process: connoisseurship, provenance, and forensics. All three bases were covered with Saint Sebastian, although precious little information has been made public to date.

The aesthetics are in its favour. The drawing doesn’t look too perfect, too refined. The artist wasn’t sure how he wanted the saint positioned – he drew the legs in several different positions, and the tree before the saint (we can see lines delineating the tree trunk through those defining the saint’s legs). As The Guardian’s art critic Jonathan Jones pointed out in 2016, the sketch has ‘blobs of ink … gathered on the figure’s raised arm, and also to form his dark, shadowy belly button. That pooling of ink is so Leonardo. To me, that’s a massive clue.’ He’s right, but also correct in his use of ‘to me’, because aesthetic judgment calls are notoriously subjective (recall that some past connoisseur wrote ‘Michelange’ on this very drawing). But those are the details that distinguish authorship and help to determine that a work is not a copy.

A copy, made when looking at a finished original, will be more studied, carefully drawn, less likely to feature drips, splotches and scribbles. Devolder agrees that this is a particularly compelling clue:

In general, you would look first at how the drawing materials were used: type of brush and/or pen. You would look at the gestures and movements of the lines (hesitations, boldness, corrections, directness, curvature, and so on). How does the ink look: are there areas where the ink pooled together, transparency … and compare all these things with firmly attributed drawings.

There are similar, established works by Leonardo to which this can be compared. He is known to have sketched in a similar manner, with shifts in positioning (as in Saint Sebastian’s legs) drawn onto the same picture. A drawing of a horse with multiple leg positions comes to mind, as well as his most famous drawing of all, Vitruvian Man. Then there’s the fact that recto and verso were used. This is not unusual – vellum paper was a prized commodity in the Renaissance, and all parts were used where possible. But the combination of a preparatory sketch for a painting on one side, and optical diagrams, plus Leonardo’s distinctive handwriting, on the other, add to the aura of authenticity.

A thorough backstory reassures that the object is neither forged nor stolen

If such a work satisfies the expert’s naked-eye scrutiny, then it goes to the second test of authenticity: provenance research. Provenance is the documented history of an object’s ownership, and includes historical documents suggesting that the object fits into known history, that there is some trace of, or reference to, its having existed, lending credence to the possibility that it is a lost work, now found. Saint Sebastian fits the latter bill. In one of Leonardo’s notebooks, called The Codex Atlanticus (filled between 1478-1519), Leonardo mentioned eight drawings of Saint Sebastian made in preparation for a painting that he would never complete. One of those eight drawings is extant (at the Hamburger Kunsthalle). This would appear to be another of them.

The ownership history trail remains obscure to the general public. Tajan will have looked carefully at the doctor’s story, at whether it added up that this was one of 14 drawings collected by his father, and will have tried to learn as much as possible about the chain of ownership from Leonardo’s studio to the present day. The more background an auction house can fill in, the more interesting the item (perhaps it played an important historical role, passing through major collections), and also the safer the purchase appears, for a thorough backstory reassures that the object is neither forged nor stolen. De Bayser does not know the whole story, but he immediately saw clues as to the provenance in the object itself:

The other 13 works in the same collection were also Old Master drawings, some of them are copies, two or three are quite good quality, but we don’t know the artist yet. All on the same mount, which is interesting for the provenance. All the mounts seem to be c1900, they all have the same hand inscription on the mount. The drawing comes from an album, because on the stretcher you can see that it was cut down, and taken from a larger album. This means that there must be other drawings from the same collection and the same mount. But I didn’t find any myself.

Since the provenance findings have not been made public, we can only assume that Tajan has done its proper due diligence.

The final hurdle in establishing an artwork’s authenticity is forensic. An array of non-invasive scientific testing methods is available that can help assure an object’s age, but these cannot guarantee authorship. Perhaps surprisingly, forensic testing is rarely turned to in the art trade, even with such extremely expensive items as this one. If an object looks good, and the provenance checks out, then it is usually accepted as genuine, and sold. Forensic testing usually takes place when some red flag is raised in the connoisseurship or provenance studies, or if someone who acquires it later grows suspicious. In this case, Saint Sebastian was likely tested at the Louvre in November 2016: since ‘it was listed as a tresor national by the Ministry of Culture shortly after, we can assume the results were positive,’ says de Bayser. Besides, a government wishing to keep the work in France would have wanted to confirm its authenticity before committing tax-euros to purchasing it.

Forensic tests are best at spotting anachronisms, details that might give away an object’s imposture, like some pigment or material found in an artwork that post-dates the period in which the work was supposedly created. The German forger Wolfgang Beltracchi, for instance, was caught when titanium white, a modern substance, was found in 2008 in a painting ostensibly created before titanium white was available. Testing can also date organic material (such as paper) to a certain period, often accurate to within a few years. What forensic testing almost never does is guarantee authorship. It is better at weeding out than honing in. Presumably, when this work was tested, no flags were raised – everything dated as it should to feasibly allow authorship by Leonardo. Effectively, science offered a double-negative to support the conclusions of the connoisseurship and provenance examinations.

But art history is pocked with compelling copies, often by members of an artist’s studio, as well as forgeries, which can tax and strain even the most assured expert eye. This is why the double-negative assurance (the business of authenticating originals) is so important. The art historian Katy Blatt’s 2011 book on Leonardo’s painting The Virgin of the Rocks concerns two versions of it – both by Leonardo. ‘Historically, the second Virgin of the Rocks at the National Gallery, London, has been seen by scholars as a lesser copy,’ she said. Having the painting authenticated ‘was helpful to maintain [the gallery’s] standing as a global centre for art treasures; and it certainly boosted their ticket sales; the 2011 Leonardo exhibition attracted 323,897 visitors, more than six times the numbers normally admitted to exhibitions.’ Concern that Salvator Mundi might not have been the real McCoy was such that the scholar Jehane Ragai added a section on it to the second edition of her book The Scientist and the Forger (2015).

There is also precedent to illustrate the dangers of a most prominent scholar authenticating a work with certainty, and leading others to follow. During the Second World War, the art forger Han van Meegeren tricked the world’s leading Vermeer specialist, Abraham Bredius, into authenticating his forged Vermeers. When Bredius pronounced them to be part of a long-lost period and some of Vermeer’s finest creations, other scholars in the field did not dissent. Van Meegeren was able to sell his ‘Vermeers’ to the Nazi art aficionado and head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering. It was only when van Meegeren went on trial after the war, for having sold Dutch cultural heritage to the enemy, that Bredius’s embarrassing error was made public. At first, no one believed that van Meegeren had actually sold Goering a forgery (and therefore, he argued, he should not be executed, thank you very much) because of Bredius’s belief in its authenticity. Only when van Meegeren painted another ‘Vermeer’ while incarcerated did the egg on Bredius’s face come clearly into view.

No fraudster has bothered to create forgeries that would fool conservators in their labs

When de Bayser called Bambach of the Met, whose informed, yet inevitably subjective opinion can add so many zeroes to the value of an artwork, she proclaimed the Saint Sebastian drawing to be ‘quite incontestable’. It was, she added, ‘an open and shut case’. Most of the world agreed, but it was her revered opinion among Leonardo scholars that propelled agreement. France is all in. On 5 January 2017, the Ministry of Culture announced a temporary export ban on the drawing, giving it 30 months to match the €15 million asking price and first dibs on buying it. Now Bambach is planning an academic article to provide the first in-depth analysis of the drawing.

It would be nice if the provenance and forensic test results were published along with it. But this is not always the case. Owners and dealers are notoriously reticent about provenance, considering it a private matter – but in recent years the most conscientious members of the art world have taken care to be transparent and publicise as much of an object’s history as is known, thereby demonstrating that there’s nothing to hide. It remains unusual for forensic test results to be made public (if they are made at all), but they are still the most compelling way to assure that an object is not a forgery: almost no fraudsters in history have bothered to create forgeries that would fool conservators in their labs. They don’t have to. If the work and the provenance (which, alas, can also be forged or doctored) both look good, forgers know that it is highly unlikely that the work will be tested at all.

One thing is for sure: the French government has given the drawing its stamp of approval, which means that, whether or not it can raise funds to buy the work, the world believes this to be a Leonardo. Its decision – and a €15 million investment – rests largely on the personal opinion of a single expert – Bambach. ‘My heart will always pound when I think about that drawing,’ she told The New York Times in 2016. That is not to say that she is wrong – I’m quite certain that she is right. But for all the technical gadgetry available, art-world decisions still rest largely on the subjective conclusions of individual, ultimately fallible, specialists. Forensics merely help matters along.

There is much hanging in the balance for only a ‘feel’ as guide. As we have seen with the acquisition of Salvator Mundi by an Arab billionaire, Leonardo’s works have become trophies that indicate cultivation, wealth, cultural preeminence. To own a Leonardo is the highest sign of erudition. The fact that Salvator Mundi (whose public stamp of official approval came more by way of curatorial say-so than through the hard work of conservators), is – by several hundred million dollars – the world’s most expensive artwork, is a bonus in a world in which superlatives summon the most headlines, and where wealth and cultivation are thought to go hand in glove. Now the Louvre Abu Dhabi has its iconic showpiece, effectively putting Abu Dhabi on the high-culture map. With only a few dozen works across the globe certain to be by Leonardo’s hand, even a relatively simple and small drawing, such as our Saint Sebastian, bears a weight of expectation – and quiet desperation – for its authenticity far greater than its few grammes of mass.

Noah Charney

is a professor of art history and the founder of the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art (ARCA). His books include The Art of Forgery: The Minds, Motives and Methods of Master Forgers (2015), the Pulitzer-nominated Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art (2017), co-authored with Ingrid Rowland, and The Museum of Lost Art (2018).