The painting was discovered by a curator at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, Italy,

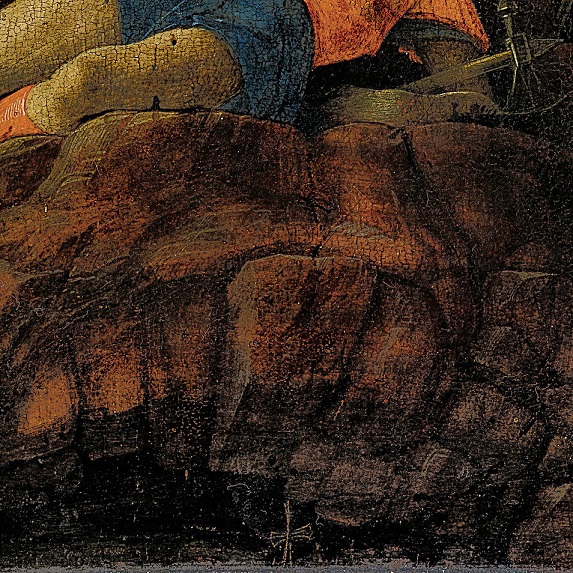

Andrea Mantegna The Resurrection of Christ (1492-93). Photo: courtesy of Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

A 15th-century painting that was written off as a copy and stashed away in storage for almost a century has been attributed to the Renaissance master Andrea Mantegna. The sensational discovery was made at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, Italy and has been confirmed by the world’s foremost Mantegna expert, Keith Christiansen of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Resurrection of Christ (1492–93) was discovered in the museum’s storage facility by the Carrara’s curator Giovanni Valagussa, who came across the painting while working on a catalogue of the museum’s holdings. In the 1930s, the painting was dismissed by art historian Bernard Berenson as a copy of a lost Mantegna painting. It had languished in storage ever since. But Valagussa was immediately impressed by the quality of the work.

The gold crucifix, a vital clue to the attribution from Andrea Mantegna’s The Resurrection of Christ (1492–93). Photo courtesy of Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

Speaking to artnet News, Christiansen said a key observation by the curator drove the discovery: Valagussa spotted the tip of a gold cross at the bottom of the composition, seemingly floating in space. “Giovanni noticed that painted in gold is a little banner, the same banner Christ is holding as he comes out of the tomb,” he explained.

The banner was attached to a pole that was cut off, which indicated that the painting had been split into pieces—a common practice in the Renaissance era. Valagussa’s mind immediately turned to Mantegna’s Christ’s Descent into Limbo in which Christ is shown holding a pole without a banner. “We put the two images together, and bingo! The rocks all match up, the little banner comes together, mystery solved,” Christiansen said.

Vallagusa’s hypothesis was supported further by an analysis of the rear of the painting, which featured a narrow wooden beam attached to the panel to stabilize and prevent warping. According to the Wall Street Journal, beams like this were typically attached to the upper and lower edges of a painting in places where the panel is most susceptible to warping. But this one was in the middle, suggesting that it must have been either the upper or lower part of a larger composition.

Andrea Mantegna Christ’s Descent into Limbo (1492–93). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

According to Christiansen, Renaissance artists often cut up paintings “for practical reasons, usually to fit the decorative schemes of a collection.” In this case, he added, “Mantenga’s name was so prestigious that instead of throwing away the little upper part, it was saved.” The lower half of the divided painting, which belongs to a private collector, was bought at Sotheby’s, New York in 2003 for $28.5 million.

Valagussa contacted Christiansen for a second opinion after rediscovering the painting. As a leading expert on the artist, Christiansen was able to confirm the curator’s theory. “My colleagues in Bergamo very generously sent me images to see if I was in agreement of what they thought, and with the evidence they had gathered, I didn’t see any objections that could be made,” he said.