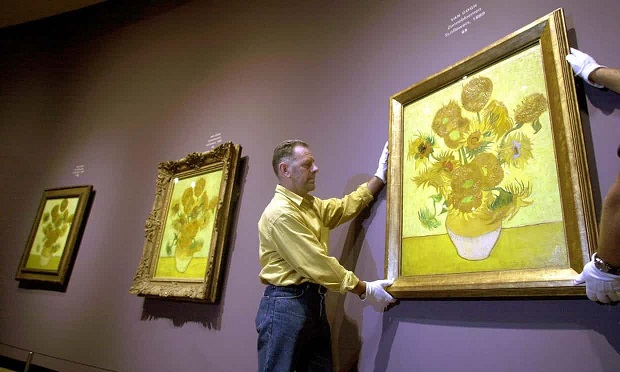

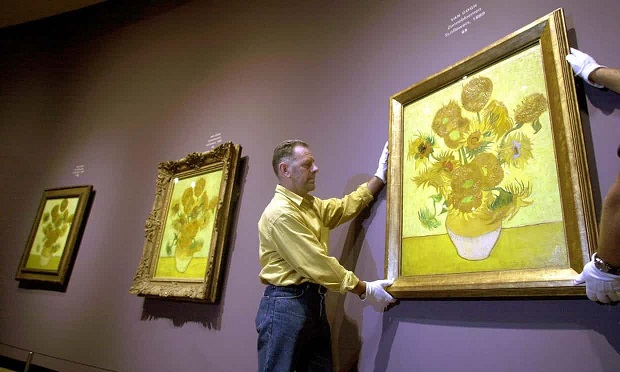

Van Gogh’s sunflowers.

Three versions of Van Gogh’s sunflowers are seen together at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Photograph: Robbert Slagman/EPA

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is reviewing how it displays the artist’s Sunflowers painting after a pioneering new technique revealed the painting’s petals and stems were withering to an olive-brown colour as a result of his use of a light-sensitive yellow paint.

A laborious x-ray scan of the painting’s canvas has discovered that Vincent van Gogh used two different types of a chrome yellow paint, one of which is more liable to degrade under light.

The change in the 1889 painting, one of a series of sunflowers by Van Gogh, is so far not visible to the human eye but, over time, the painting is set to lose some of its vibrancy in the pale-yellow background and the sunflowers’ bright yellow petals and stems, where the sensitive pigment was mixed to achieve the right green hue.

The orange parts of the background to the flowers is unlikely to degrade in any significant way as Van Gogh used a less sensitive yellow paint, with a lower content of sulphur.

“It is very difficult to say how long it would take for the change to be obvious and it would depend a lot on the external factors,” said Frederik Vanmeert, a materials science expert at the University of Antwerp, who was part of the team examining the painting in research commissioned by the museum.

“We were able to see where Van Gogh used the more light-sensitive chrome yellow, the areas that the restorers should look out for over time for discolouration ... We were also able to see that he used emerald green and a red lead paint in very small areas of the painting which will become more white, more light, over time.”

The discovery, following two years of analysis by a team of Dutch and Belgian scientists, is being assessed by the Amsterdam museum, which hosts the world’s largest collection of the artist’s works. The museum lowered the lighting in its rooms five years ago in an attempt to best conserve its 200 paintings and 400 drawings.

The scientists used macroscopic x-ray imaging to examine the canvas, section by section, in a process described as “chemical mapping”.

Such is the level of detail in the images that the scientists were able to observe the ordering of the elongated crystallites in the light-sensitive chrome yellow along the direction of Van Gogh’s brush strokes. More than half the painting contains some of the more sensitive pigment.

Joris Dik, a professor of art history and materials science at Delft University, described the technique as being “as if you are taking a satellite picture of the Netherlands to see any weak spots in the dykes”.

The Museum of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers painting is one of the second series of paintings of that name. The first series, painted in Paris in 1887, depict the flowers on the ground. The second set, painted in Arles, shows them in a vase and is perhaps the most widely recognised.

The head of collection and research at the museum, Marije Vellekoop, said the study had ramifications for a whole range of the painter’s works. “Obviously, we monitor the discolouration of various pigments,” she said. “At the moment, we are processing all the research results of this iconic painting, after which we determine how we will pay further attention to discolouration in our museum. We know that the discoloured pigment chrome yellow has been used a lot by Van Gogh, we assume that this has also been discoloured in other paintings.

“Discolouration of pigments is a topic of research that is of great interest to us since Van Gogh, as did his contemporaries, used several pigments that discolour over time. In the case of chrome yellow, this recent study provided new information on the location of the light sensitive type of chrome yellow in our Sunflowers. This makes it possible to monitor these areas carefully.”