정준모

How Dead Artists Continue Producing Work

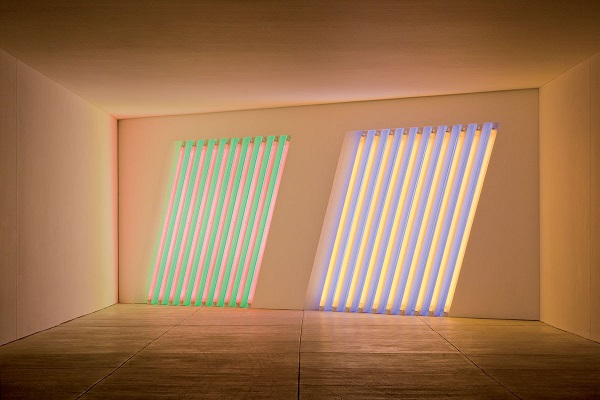

Detail of Dan Flavin, Untitled (Marfa project), 1996. © 2011 Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Douglas Tuck, 2009. Courtesy of the Chinati Foundation.

If Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. can release posthumous albums and Mark Morris can choreograph posthumous dances, then surely the estates of Constantin Brancusi and Dan Flavin

can issue work long after the artists have passed away?

The estates themselves have already answered that question in the affirmative, but the making of work following an artist’s death is not without controversy. The question of whether and how to produce posthumous work is becoming increasingly salient as a cohort of esteemed artists reach their seventies, eighties, and even hundreds, and they and those around them look ahead for how best to preserve and enhance their legacies.

Loretta Wurtenberger, founding director of the Institute for Artists’ Estates and co-author of The Artist’s Estate: A Handbook for Artists, Executors, and Heirs, said the question of whether to produce work after the artist is gone is “one of the main topics” she discusses with living artists as they plan their estate and legacy. But for artists who have already passed away, she said, the decision should be made “not on copyright issues, not on market issues—it should only be based on what the artist wanted,” she said.

Sometimes, the artist has not specified. American conceptual artist Dan Flavin’s will, for example, said nothing about the hundreds of unfinished editions of his fluorescent light “propositions,” commercially available bulbs arranged according to a specific plan and accompanied by a signed certificate. By contrast, even if subsequent disputes have emerged about his plasters and bronzes, French sculptor Auguste Rodin

was at least clear in his intentions, authorizing the executors of his estate to cast work from his molds both for public purchase and for the Musée Rodin in Paris.

Whatever the artist’s intention, as art advisor Megan Fox Kelly noted at April’s Art Business Conference in New York, an artist’s legacy and her or his posthumous market can no longer be separated.

“Protecting the artist’s market is an essential part of protecting the artist’s legacy,” Kelly said on a panel on protecting artists’ legacies.

“A path of support”

Installation view of Dan Flavin, Untitled, created in 1996 and posthumously realized in 1997, at Santa Maria in Chiesa Rossa, Milano. Photo by Paola Bobba. Courtesy of Fondazione Prada, Milano.

Installation view of Dan Flavin, Untitled, created in 1996 and posthumously realized in 1997, at Santa Maria in Chiesa Rossa, Milano. Photo by Paola Bobba. Courtesy of Fondazione Prada, Milano.

In the case of the Flavin estate, the decision on whether and how to fabricate works following the artist’s passing in 1996 fell to his son Stephen, a soft-spoken, bearded man of 54. At the time of the elder Flavin’s death, Stephen said, “things were rather chaotic,” and it seemed to him “the safest thing, the simplest thing” to ignore the estimated 1,000 to 1,700 works that had been left to him in the form of uncompleted editions (the artist usually worked in editions of three or five).

But after a decade or so—and, in particular, after a private funder for a Dan Flavin museum pulled out after the economic downturn of 2008—Stephen reconsidered his options. He realized he could sell some of those works (with “estate certificates” signed by Stephen, as opposed to “lifetime certificates” signed by Dan himself) to help cover the costs of such a project, as well as other projects such as transcribing and publishing his journals.

“It was necessary in my mind to find the path of support, and the unfulfilled editions were the way to go,” Stephen said.

The ambitions and hopes of artists’ foundations and heirs “are entirely tied up with the rate of sales, the price levels that an artist is achieving, what’s happening at auction, the placement of important works from their collection only in museum collections, what’s to happen with copyright, and how the foundation is going to manage that,” Fox Kelly noted at the Art Business Conference.

Clenched Hand

Auguste Rodin

Clenched Hand, 1984-1986

Museo Soumaya

The Kiss

Auguste Rodin

The Kiss, 1929

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Stephen eventually chose to work with David Zwirner, which began representing the estate in September 2009, shortly after it produced a recreation of Dan Flavin’s influential 1964 Green Gallery show at Zwirner’s East 69th Street location. The show convinced Stephen that Zwirner really understood his father’s work and how it was meant to be staged—and, in a neat twist, David’s father, Rudolf, had been Dan’s European dealer, and David remembered meeting the artist as a child.

The reappearance of Flavin’s work on the market surprised New York dealer Paula Cooper (of her eponymous gallery) and Douglas Baxter, president of Pace Gallery. Both gallerists had worked with the artist in his lifetime, and regularly served on a panel convened by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service that values artwork in collections or held by an artist’s heirs to determine the amount of estate tax the government will levy. In separate interviews, each recalled a determination by the IRS that no further editions of Flavin’s work would be fabricated after his death. Stephen said there was no discussion of that in his negotiations with the IRS.

In any case, the unfinished editions—which a 2005 story in the New York Times estimated were worth as much as $70 million—were not included as part of the estate at the time of Flavin’s death, Stephen said. This meant he did not have to pay the 55 percent estate tax on whatever their value would have been at the time (it could have been much less than the Times’s estimate, given that flooding the market in order to pay a hefty tax bill would have lowered the value of each work). There have been about 30 works with estate certificates sold since Dan’s passing, he estimates.

The market impact

Installation view of “Dan Flavin: in daylight or cool white,” at David Zwirner, New York, 2018. © 2018 Stephen Flavin/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

In her 2016 book on artist estates, Wurtenberger writes that “most posthumous editions will sell for about 30 percent less than originals.”

Kristine Bell, a senior partner at David Zwirner who curated a recent show of Flavin’s work at the gallery’s West 20th Street location in New York, said there is no price difference for Flavin’s work from before and after his death, though lifetime works came with a certificate signed by the artist that were often decorated with a little drawing, while posthumous works come with a certificate signed by his son. The estate is also conservative about how many works it releases onto the market. Bell said she usually has eight to ten Flavin works in her inventory at any given time, a well-rounded representation of Flavin’s practice from the 1960s through the ’90s. Approximately once a year, she requests additional works, and Stephen will tell her if they’re available.

Bell said prices in the show ranged from $750,000 to $5 million for a mix of works: some consigned by the estate, some consigned from private collections, and others loaned from private collections and an institution.

Wurtenberger notes that, for artists who produced very little work while they were alive, the difference between lifetime and posthumous works can far exceed the 30 percent average. Lifetime works by photographer Diane Arbus

, for example, begin at $25,000 and can reach over $1 million, Wurtenberger writes, citing Frish Brandt, executive director of the San Francisco-based Fraenkel Gallery, which has long represented Arbus. By contrast, Arbus works printed after her death by photographer Neil Selkirk range from $5,000 to $100,000.

Pace Gallery’s Baxter said that, while a large influx of posthumous work onto the market could dampen prices, there is also “a kind of misconception that the less work there is by an artist, the more valuable it becomes.”

“If you think about the most famous artists in the art world, Andy Warhol

, Picasso

, Calder

…they’re big artists because of the volume of their production,” Baxter said.

Installation view of “Brancusi in New York, 1913-2013,” at Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2013. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Constantin Brancusi, another artist for whom there is an active market for posthumous work, has a wide gap in prices for those works versus works made in his lifetime. The vast majority of his lifetime works are in private collections and museums, so getting one’s hands on an original is increasingly challenging. In 2017, Brancusi’s La muse endormie (1913) sold at Christie’s for $57 million, and in May, La jeune fille sophistiquée(conceived in 1928 and cast in 1932) sold for $71 million. By contrast, Paul Kasmin Gallery, which represents the artist’s estate, sells posthumous bronzes for prices in the single-digit millions. One, Torse de jeune homme(conceived in 1924 and cast in 2017), was recently available at Paul Kasmin’s booth at Art Basel in Hong Kong for an asking price of $4.5 million.

“As is the case with lifetime and posthumous bronzes by Rodin and Giacometti

, or vintage and posthumous prints by Mapplethorpe

, there is always a distinction in market value between the two,” said Eric Gleason, a director at Paul Kasmin Gallery.

That lower price point, though, can be a boon for institutions with limited resources. Museums such as the Musée d’Arte Moderne de la Ville in Paris; the Museum of Modern Art in Shiga, Japan; and the Alte Nationalgalerieand Staatliche Museen in Berlin all have Brancusis in their collections now, thanks to the availability of posthumous works. Those acquisitions, in turn, give Brancusi’s work a wider audience, helping to cement his legacy.

Baxter cautioned that having both lifetime and posthumous works in the market could cause confusion in the secondary market, if a collector with a posthumous work is unclear or “forgets” to mention the year it was cast when reselling it.

“Art collectors famously actually forget these details,” Baxter said. “And certain art collectors also have willful disregard for the facts.”

Wurtenberger, though, said museums are increasingly upfront about the posthumous work in their collections.

“The whole transparency issue has really changed,” she said. “Twenty or twenty-five years ago, when you saw a sculpture, you only saw on a plaque [a mention of] when it was produced, not when it was cast. Now you have ‘1978/2005.’ There has developed a much higher sensitivity and a higher transparency.”

What of “the hand” or “patina”?

Constantin Brancusi, Muse (la Muse), 1969, posthumous cast from 1912 plaster original. Courtesy of Norton Simon Art Foundation.

Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963. © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Billy Jim, New York. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

Brancusi left behind a selection of plaster molds for casting his bronze sculptures, which are still executed at Susse Fondeur, one of the many foundries he used in his lifetime and the only remaining foundry in France with expertise in sand-casting, a process that uses sand to create the molds, Gleason said.

Despite that continuity, some consider the notion of posthumous bronzes inimical to how Brancusi worked, and therefore closer to a reproduction than an original artwork.

“Brancusi worked on each sculpture, even in an edition,” said Elizabeth Szancer, an art advisor and the curator of the Ronald S. Lauder Collection. Lauder, a cosmetics magnate and president of the World Jewish Congress, is one of the few Americans to collect Brancusi in-depth. “He tweaked it with each task of producing the sculpture…so the artists’ hand played a very large role in the result,” she said, adding she did not think Lauder would consider a posthumously produced work of the same artistic value (“much more mechanical,” she said) as a lifetime one, of which there are only around 220, according to Gleason.

For conceptual artists such as Flavin, whose work was itself a response to the fetishization of the hand of the individual artist, that question is moot. Instead, collectors be might concerned over whether the lamps in their works were “originals”—say, green lamps from the stockpile of 600 he accumulated in his lifetime from the Sylvania company, or those retained by people who worked with him earlier in his career, such as Paula Cooper, whose stash of bulbs is mentioned in a 2013 New Yorker story.

Bell said there is a supply of lamps “still being produced in the exact same fashion” in the palette Flavin used in his lifetime. Replacement lamps can be bought through Zwirner’s website for $11 to $70 per piece.

“Old fixtures should be replaced anyhow,” Bell said. “If you own a fixture that dates from ’68 or ’69, they look terrible. They’re all banged up. You should replace them; there’s no fetishizing of the fixture.”

Last year at Frieze Masters in London, David Zwirner’s booth included Flavin’s first fluorescent sculpture: the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi) (1963), a single neon tube in golden yellow, placed at a 45-degree angle to the floor. The gold color, said Bell, refers to Byzantine

icons, who are often haloed in gold in paintings and mosaics.

“It proposed an endlessness,” said Bell. “It had an infinite potential to go on forever.”

In that sense, it was emblematic of the careers of the two artists themselves.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari