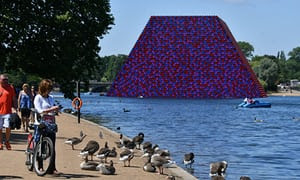

It sits out on the lake, bigly. Constructed from 7,506 standard oil drums, the London Mastaba interrupts the view. More than that, it is the view. It is unmissable. Floating on London’s Serpentine, and tethered to the lake’s shallow bottom, Christo’s first major London project is an alien presence, its sides rising at 60-degree angles from the placid waters. The end walls drop sheer. A geometric presence, a blockage, a giant toy, a feat of engineering, it is a sculpture. It is a thing.

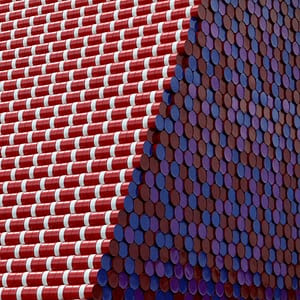

The birds look unconcerned by the 83-year-old’s creation. Fish, often attracted to underwater structures, doubtless swim and lurk underneath. The sculpture’s footprint covers 1% of the artificial lake’s surface and rises 20 metres above the water. The sides of the barrels are painted red, with a white stripe circling their circumference, giving the side-view of the sculpture the appearance of relentless cartoon brickwork. The circular barrels’ ends are variously blue, a different red or a dusky mauve. Their arrangement seems a kind of random pixilation, though the order is meticulously copied from the artist’s working drawings.

The colour feels a bit inert but adds to the sculpture’s disruption of Hyde Park’s bucolic vistas, the sky above, its reflection in the water. On a still day, the sculpture reflected in the water would doubtless look even more peculiar. I thought less of land art – the kinds of things Nancy Holt, Robert Smithson and Michael Heizerconstructed in the American west – than I did of rock festival stages.

Less timeless, more old hat, the London Mastaba somehow lacks a sense of wonder. It has none of Daniel Buren’s joyousness and lightness, nor the hilarity of certain Claes Oldenburg public sculptures and proposals, nor the mute gravity of Richard Serra. No delicacy, no grandeur.

In his long career, Christo has made some spectacular interventions, both visually stunning and complex pieces of engineering – wrapping Australian cliffs and the Reichstag in Berlin – and politically complex in their processes of persuasion and negotiation. He has blocked a Paris street with a barricade of barrels, and proposed barrel sculptures for the Suez Canal and a Mastaba for the United Arab Emirates – a work that, it is claimed, would be the largest sculpture in the world. As an object, perhaps, and if such superlatives weren’t in any case somewhat meaningless.

Proposals often lay in wait for decades, waiting for a time and place, an opportunity. But the political dimension of Christo’s work appears to me weak. These are oil barrels, but the global economics of oil are hardly touched on. A mastaba is the name given to a particular kind of bench built as a seat outside houses in ancient Mesopotamia, whose form Christo has enlarged. Are we supposed to think of a kind of communality?

Totemic … the London Mastaba is 20m high, 30m wide and 40m long. Photograph: Nils Jorgensen/Rex/Shutterstock

Christo funds all his work himself. Over in the Serpentine gallery, room after room is dedicated to cans and barrels, drawings and photographs and models for projects made and unmade. Barrels stacked into columns, some topped with a horizontal barrel, arrangements of barrels large and small, naked rusted barrels, dirty barrels and painted barrels and barrels wrapped in cloth, whose surfaces are lacquered and distressed. Christo began using the barrel, and before that the tin can, in 1958. For most of his career Christo worked with his wife, Jeanne-Claude, until her death in 2009.

There isn’t much development in the sculptures, most of which in any case were made in the 1960s. The overall feel is totemic, literal, and repetitive. I shall avoid the obvious barrel gags. Out on the lake, Christo’s Mastaba catches the light and casts its shadow, a gigantic bath toy afloat on tepid waters.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Barrels and the Mastaba 1958-2018 is at the Serpentine Gallery, London, until 9 September