Speaking to three artists who escaped from North Korea

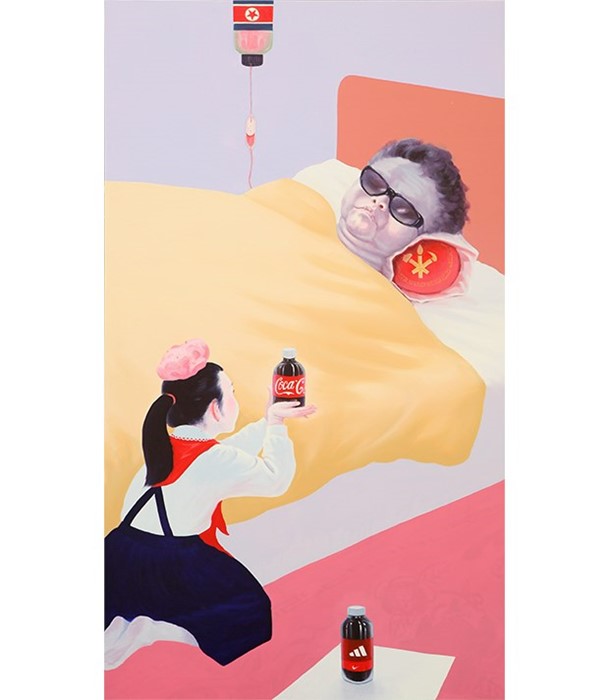

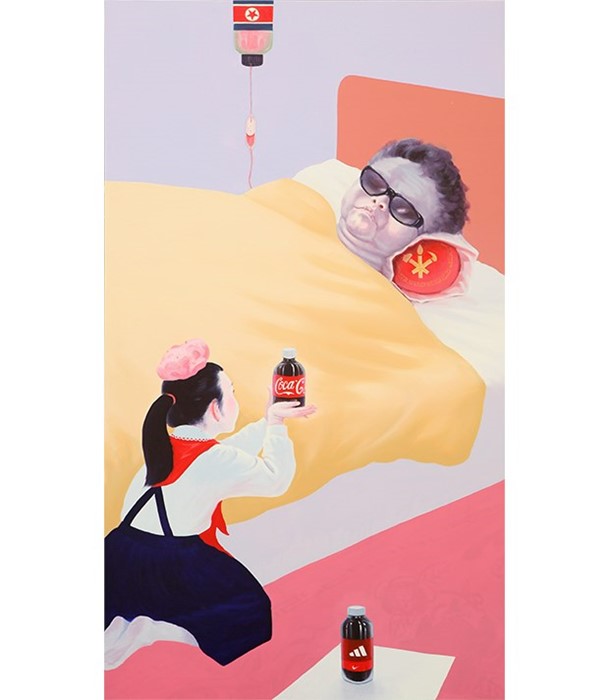

“Some Take Medicine”Sun Mu

Speaking to three artists who escaped from North Korea

Choi Sung-gook, Sun Mu, and Kang Nara discuss how they defected from the DPRK and the reasons why they left everything behind

North Korea, infamous for countless media headlines centring on threats of nuclear warfare or most recently with the historic Korean peace summit that took the world by surprise, is no stranger to repressing, or completely controlling, artistic expression.

Since 1953, approximately 300,000 North Koreans have escaped the isolated country, with 31,000 defecting to South Korea. 70 per cent of those who escape are women. Nine out of ten are either caught by the border guards in China and sentenced to life in prison, or killed. Still, every year, an estimated 1,000 North Koreans escape. Out of this minority, a tiny handful of artists have fled, to create new work, new perspectives, and new lives, but to ultimately live out the art of expressing themselves without fearing for their lives.

Just 35 miles above Seoul, freedom and art are understood differently – with most North Korean art created through the lens of the regime. Socialist Realism of the 1950s was heavily influential, living on via the glorification of the North Korean leaders, the celebration of the regime’s political ideologies, the love for traditional Korean landscapes and nature, and the depiction of “everyday life” that is essentially made complete through work or labour. Although the portrayal of human expression is still meticulously captured in the most intricate paintings, such as in chosonhwa (Korean painting on rice paper), nothing must ever go against the state – or the artist and their family face severe punishment. Below, we meet three artists who escaped the DPRK.

“When you live, you always somehow live illegally” – Choi Sung-gook

CHOI SUNG-GOOK

Before he fled from North Korea, Choi Sung-gook was an animator in Pyongyang’s best animation studio, SEK Studio. Creating propaganda films for the regime and editing Disney films like The Lion King when Disney had outsourced work to North Korea in the early 2000s.

“My everyday life in North Korea focused on ‘What do I earn more money from?’ Or who is going to expose me?” Choi says, recounting his daily paranoia concerning the regime and his desire to create more work outside of his official assignments. “If someone does capture me, then I have to figure out a way to survive and escape – I thought about that endlessly. I was always curious about the world outside of North Korea.”

While working at SEK, Choi realised that his foreign colleagues were earning significantly more than him. He eventually began smuggling South Korean films through DVDs from China and would Photoshop people’s portraits so that they looked like South Korean celebrities with the most popular hairstyles, or with a certain South Korean fashion attire to appear more “cool”. Once he realised this lifestyle would land him in prison, he defected from North Korea in 2010, following in his mother’s footsteps, who had escaped two years earlier.

“Have I been afraid of the government? Of course. You live every day in fear of the government. When you live, you always somehow live illegally,” he explains. “What is considered bad in North Korea is when you do anything for yourself. If I have to make money to survive on my own, that desire to do so is illegal.”

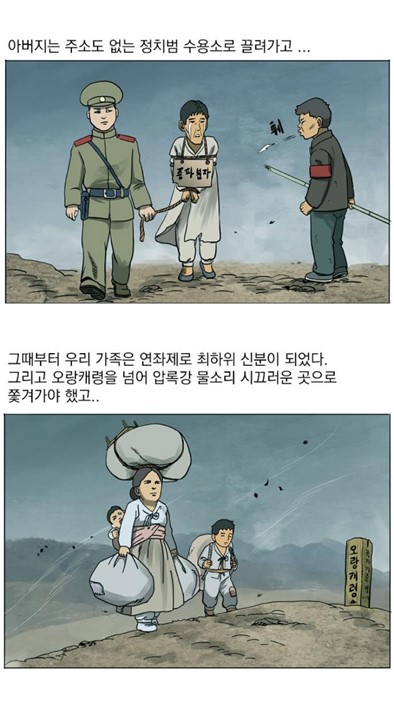

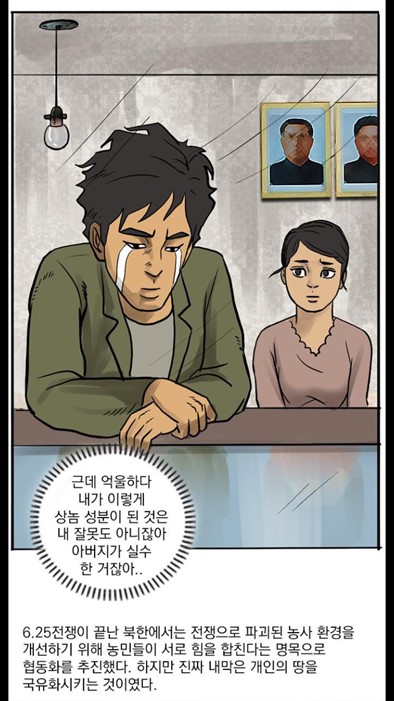

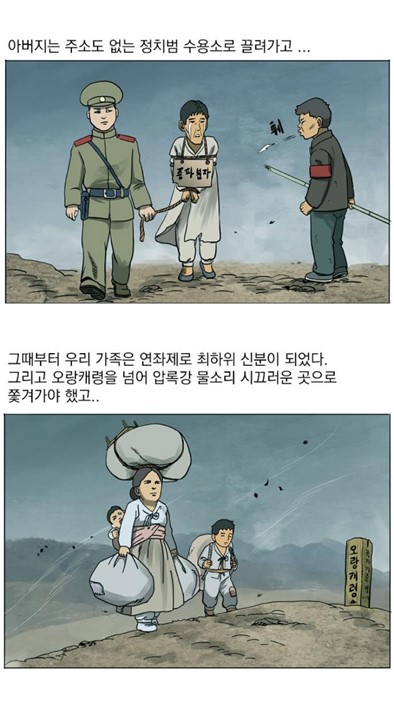

Images from "Rodong Simmun"Choi Sung-gook (Naver Webtoon)

Referring to the life he saw in South Korea through the smuggled films, Choi explains, “In North Korea, you are told what to do, whereas, in the South, you need to know what to do for yourself. When you see South Koreans, you see that they are openly living out these ‘illegal’ careers that they choose for themselves.”

“(The North Korean government) doesn’t want its people to live well. If people had access to the goods that they wanted and ate well, then they will gain strength and rebel. That’s why the regime always starves you and makes you hungry. They make you live like that forever.”

In South Korea, Choi worked for a radio station that broadcasted information to North Korea for those wishing to defect. But in terms of creating art there, Choi had difficulty relating to the South Korean cartoons due to the lack of political propaganda images, patriotism, and war references that he was so accustomed to in the North. From February 2016, he began to draw cartoons – ’webtoons’ – which depicted the lives of North Korean defectors in the South.

His webtoon “Rodong Shimmun” – a play on words meaning ’labour interrogation’ instead of Rodong Shinmun, the national newspaper in North Korea which means ’labour newspaper’ – is viewed by tens of thousands of visitors. Its goal is to conjure more empathy between North and South Koreans.

“Freedom to me is something worth fighting for” – Choi Sung-gook

The comics Choi creates reflect the cultural differences that North Koreans face as they begin to live new lives in South Korea, using South Korean humour to relay the struggles faced by defectors.

For example, one of Choi’s cartoons depict North Koreans arriving at a debriefing centre in the South to settle housing issues, but they mistake the South Korean agents for North Korean security guards and wonder whether they will be tortured.

“I want to be an artist who raises awareness about harmonising North and South Korea. Even if there is reunification sometime in the future, we will truly need to be aware of our cultural differences. The fact that people listen to my voice and what I have to say is fascinating.” He adds, “To me, cultural harmonisation is stronger than a nuclear bomb. As someone who has lived under an authoritarian regime in North Korea, freedom to me is something worth fighting for.”

Images from "Rodong Simmun"Choi Sung-gook (Naver Webtoon)

SUN MU

The notion of freedom void of repression struck a chord in Sun Mu, who escaped from North Korea in 1998 while working as one of the country’s best propaganda artists. During his time in the army, Sun Mu was assigned to paint propaganda murals and posters for the government, with the belief that he was honouring Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Un. Although he had some flexibility, tweaking the details of the North Korean soldiers'’ uniforms, his main agenda was to always glorify the regime. Some of his works featured North Korean soldiers slitting the throats of American soldiers.

Once in South Korea, he began experimenting with the propaganda style he was accustomed to, using slogans like ”Destroy capitalism!” and picturing tiny South Korean soldiers running away from the North Korean Army. His satirical and provocative work in the South quickly caught widespread attention for the ways in which it captured the North Korean military propaganda aesthetic with a sharp satirical twist. Such as Kim Jong Il, painted in pink and wearing tracksuit bottoms, Kim Il Sung with a flower in his hair, or Kim Jong Un wearing Mickey Mouse ears.

”When I Iived in North Korea, I did whatever the political party and government told me to do. We were all educated to be loyal to Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Un,” he says. “If North Korea was like South Korea is today, I would have stood up and protested.

”As the happiest nation in the world, we were struggling to live every day. So I was curious as to how the people in ‘rotten capitalist countries’ were living.”

“If North Korea was like South Korea is today, I would have stood up and protested” – Sun Mu

Sun Mu was one of the few artists creating propaganda posters in the military, but due to the famine of 1994 – 1998, he fled North Korea at the age of 26. Like many other North Koreans, he swam across the Tumen river at night to China, travelling to Laos, and Thailand, before reaching South Korea.

”I went to the border to get help from my relatives who were already living in China but it didn’t turn out as expected. I entered China thinking that I would return to North Korea (after earning some money),” Sun Mu reveals.

”But I realised that it isn’t right for people to live without status, position, or worth in society. So instead of going back to North Korea where I would die, I headed to South Korea.”

The freedom to have political and artistic expression in South Korea gave him the space to create paintings filled with stark, satirical messages of the North Korean regime, but it also attracted controversy and treated the safety of his family still living in North Korea. Under the “Three Generations of Punishment”, three generations of a family can be disciplined by the North Korean government if a relative has gone against the state in any way.

At his first exhibition in Seoul, South Korean visitors reported to the police that Sun Mu was spreading Communist ideologies through his paintings. It seemed that even South Koreans were not used to satirical paintings which featured Kim Jong Un or Kim Jong Il, and that any art piece with the leaders is often be interpreted as Communist propaganda.

”You think you are speaking the same language in South Korea, but you’re not really. A 70-year-long division creates a cultural divide. If there is no understanding between the two sides, that brings misunderstanding and hatred,” he explains.

“Leaders”Sun Mu

Sun Mu is no stranger to controversy. In his documentary, I am Sun Mu, directed by Adam Sjoberg, his exhibition, Red, White, Blue – named after the colours of the North Korean flag, which took place in Beijing, where art is heavily regulated – allowed visitors to step on the portraits of North Korean leaders with Santa Claus hats. His portrait of Kim Il Sung standing below an upside down North Korean flag, with the text ”God of Korea”, was pulled from the Busan Biennale in 2008 for a fear of an uproar.

With talks on peace or denuclearisation taking place, Sun Mu’s work still captures what many miss when speaking about North Korea; that the details and magnitude of intolerable human suffering are so often overlooked. As mainstream attention gravitates towards nuclear bombs or Kim Jong Un meeting Trump.

“I believe that freedom is my own personal responsibility,” he says. “To be an artist is to be someone who can freely communicate to the world; someone who can tell a story about both the past and present, along with the future.”

Sun Mu still dreams of exhibiting his work one day in Pyongyang.

“Take it off and Play”Sun Mu

KANG NARA

Just four years ago, now reality TV star and art student, Kang Nara, escaped North Korea, nearly dying along the way. She swam across the Yalu River into China and almost drowned after being swept by a current. Her mother had arranged a broker to meet her in China in order to avoid human traffickers and North Korean guards. Over 14 days, she travelled to China, Myanmar, and Thailand, before finally arriving in South Korea.

”My mother first defected from North Korea eight years ago and I missed her terribly,” Kang says. ”I was 11 at the time. If it weren’t for my mother, I would not have escaped North Korea. My sole purpose was to be reunited with her.”

Kang comes from a more privileged background in North Korea, which sets her story apart from most other defectors. ”I came from a well-off family, so I would attend school and get tutored in the evenings or go shopping in the black markets. It was as if I had left a holiday because I had been so happy.”

Kang Nara via Facebook

Yet despite her safe childhood and sheltered naivety from the poverty around her, she began to dream of life outside of North Korea, helped by the USB sticks smuggled from China, like Choi had done.

”I watched a lot of Chinese, Russian, and Indian movies and kept thinking about how people in the films could freely wear blue jeans, earrings, and short skirts. I wondered why my country wouldn’t allow women to do the same. Was there some kind of idea behind the clothes that they wouldn’t tell us? I started to think like this from then onwards. I even began to sometimes wear them in back alleys when I was by myself.”

Even in South Korea, North Korean women face a discrimination different from that of North Korean men. Their perilous struggles, regardless of the fact that many having been raped or tortured, are exoticised, and the media romanticises the juxtaposition of their ”pure femininity” with the oppressive regime from which they have fled. Kang is just one of many North Korean women who has been cast on a South Korean reality TV show in order to demystify the enigma of North Korea to South Koreans. However, the portrayal of North Korean women as fetishised entities deters mainstream efforts to understand the stories of these women as individuals who have put their lives on the line to escape a repressive society.

”When I first arrived to South Korea, the colloquial language was the most urgent thing to understand. Whether going to the supermarket or to classes where my North Korean accent would surface, I always worried about people staring at me weirdly or thinking that I was strange,” Kang Nara reflects.

”Because of this, I even pretended that I was mute by moving my hands. I kept watching dramas and movies to get rid of my accent, to the point where today, nobody really believes me when I say that I come from North Korea.”

“If it weren’t for my mother, I would not have escaped North Korea. My sole purpose was to be reunited with her” – Kang Nara

Growing up, Kang Nara had wanted to be a painter, but her dreams changed once she arrived in South Korea. She now stars in the South Korean reality show Moranbong Club, where two male hosts interview a panel of North Korean women defectors. The women sing, dance and perform as if in a talent show.

Kang Nara was also finally reunited with her mother, and refers to this as the moment that she ”earned her freedom”.

”I have been able to do everything that I wanted to and I want to make my dream of becoming a famous actress a reality. If reunification does happen, then I wish for my family and friends in North Korea to be fairly treated,” she said.

”Since I am an actress who will be able to understand the South Korean colloquialism, language differences, and nuances, along with the North Korean dialect, I would like to become an actress who transcends the divide between the North and South and unites us together in freedom.”