No one art festival can do everything, but FRONT has made a bold inaugural effort to establish itself as a new art destination.

Clevelanders of all ages enjoying themselves at “Judy’s Hand Pavilion” (2018) by artist Tony Tasset for FRONT International. (all images by the author for Hyperallergic)

CLEVELAND, Ohio — The inaugural FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art is described by founder Fred Bidwell as an all-out effort to put Cleveland on the radar as an international art destination, and described by The New York Times, in an article cited prominently on the festival website, as an endeavor that “offers artists the canvas of Cleveland”— and this it absolutely does. Scores of participating artists and nearly three-dozen venues across Cleveland, Akron, and Oberlin, have contributed to eleven “cultural exercises” and 20+ official installation sites, which include museum exhibitions, commissions, site-specific interventions, public programs, residencies, publications and research projects.

All this has been thoughtfully and thoroughly organized under the curatorial auspices of Artistic Director Michelle Grabner, at the behest of Executive Director and CEO Fred Bidwell who, along with his wife, Laura Beth Bidwell, is a crucial booster for the arts in Cleveland. (In addition to the couple’s personal collection of contemporary art, with an emphasis in photography, they founded the Fred and Laura Ruth Bidwell Foundation which, in 2013, opened Transformer Station, a contemporary art exhibition space on Cleveland’s West Side.) Fred Bidwell makes no bones about FRONT’s objective to put Cleveland on the map as a travel destination for art lovers, and the various contributing bodies and individuals have spared no expense in the 3½ year journey toward making it a reality.

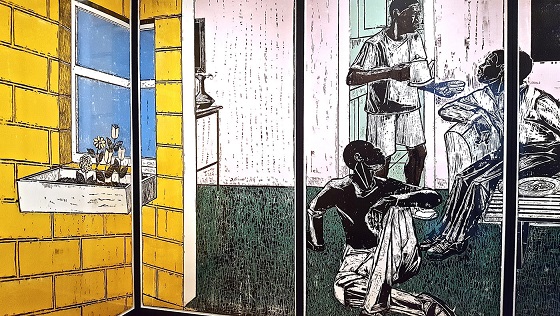

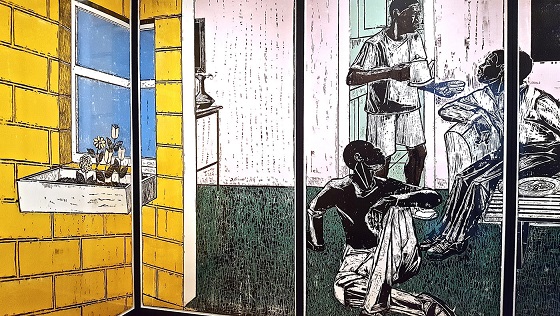

An art happening of this scope and magnitude cannot, of course, be summed up easily, but there are a number of outstanding moments. There are some gems to be appreciated in the context of regular art venues, such as Untitled (1999), a 12-panel, 8-color woodcut by Kerry James Marshall that wraps around three walls of a small gallery space within the Cleveland Museum of Art (as well as an adjacent gallery filled with sketches and other ephemera); “Brutalismo-Cleveland” (2018), a new commission by FRONT from Brazilian artist Marlon de Azambuja, which is perfectly suited to the glass-box gallery at CMA in which it is displayed; and the eerily post-apocalyptic vibe affected by Josh Kline at MoCA Cleveland, with his gallery full of fractured furniture and large children’s toys, sculpted in lighter-weight materials, but rendered to look like the cast-concrete, ashy remains of a conflict alluded to in the title, “Civil War” (2017). The Martine Syms installation at MoCA, with the artist’s signature blend of interdisciplinary information overload — via video surveillance, performance, video, wall text, and reconfigured mass media — was nearly impossible to receive in the context of a busy opening night event, but merits a visit to MoCA all on its own.

“Brutalismo-Cleveland” (2018), a new commission by Marlon de Azambuja, at Cleveland Museum of Art, installation view. Images on the wall by Luisa Lambri.

Detail of “Untitled” (1999) by Kerry James Marshall at Cleveland Museum of Art.

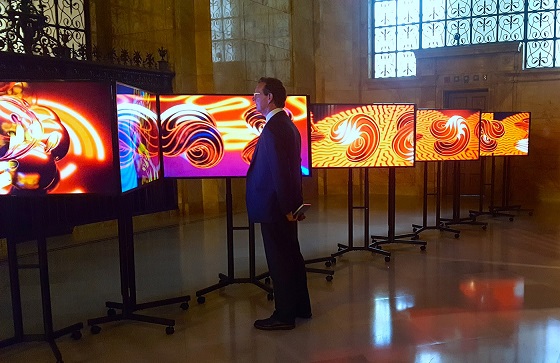

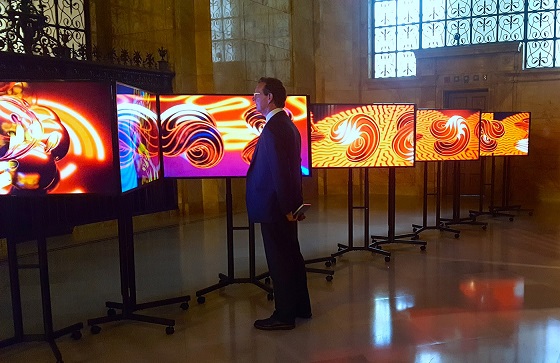

However, it is in the less conventional venue that FRONT’s offerings, and Grabner’s curatorial efforts, really shine. Philip Vanderhyden’s “Volatility Smile 3” (2018) is an iteration of his very contemporary, multi-screen digital collage work that in no way blends with its surroundings at the baroquely ornate Federal Reserve Bank in downtown Cleveland. And yet, the work inspired by Vanderhyden’s feelings of financial insecurity — “volatility smile” is a term for a common graph shape that describes a market dip formed by a group of options that share the same expiration date — strikes an incredibly tense conceptual and aesthetic balance in a space literally designed to inspire confidence in the capitalist system.

FRONT Executive Director and CEO Fred Bidwell takes in “Volatility Smile 3″ by Philip Vanderhyden at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

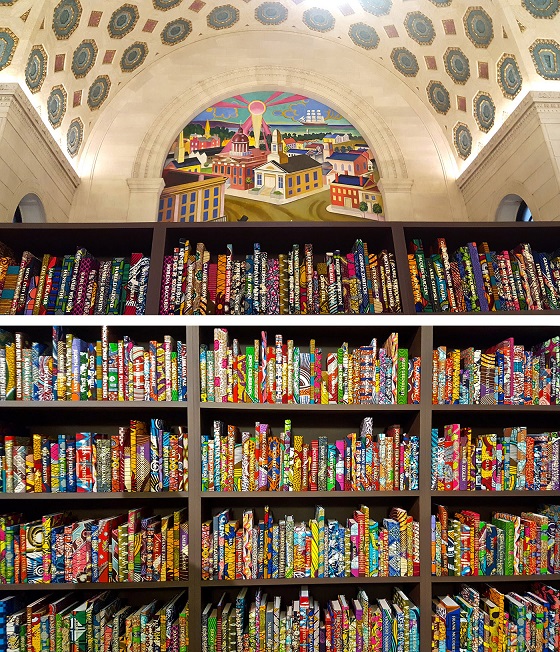

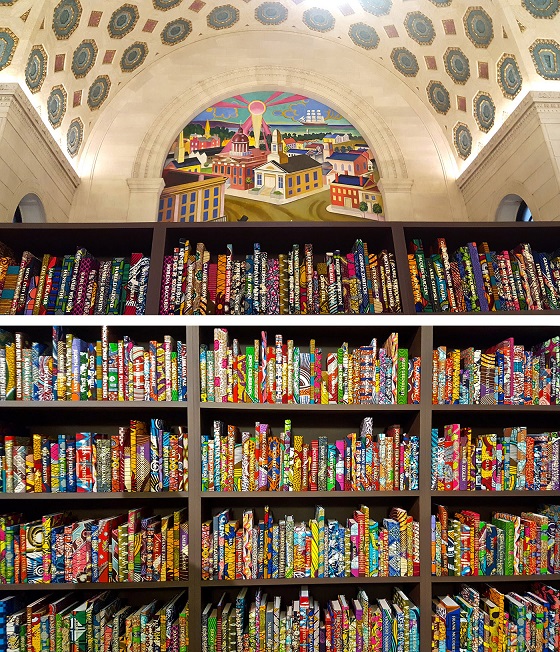

Likewise, there is an incredible impact to the placement of “The American Library” (2018) — a sequel to Yinka Shonibare’s 2014 installation, “The British Library” — sited at the Cleveland Public Library main branch downtown. First, visitors encounter a double-sided wall of books wrapped in Dutch wax print fabrics; a double-take reveals that these are artworks, not library books. Then comes the slower-breaking revelation that all of the 6,000 names gold-embossed on the book spines — many recognizable as names of contemporary celebrities and some 15% of them specific to Cleveland — denote people who are either direct or generational immigrants to the United States. The vibrant fabrics, which create an exceptionally satisfying relationship with the library’s surreal WPA-era mural in the installation’s background, serve as visual metaphor, in that they are culturally identified with Western Africa, where they were sold, but are in truth a product of Holland made in Indonesia. Considering our country’s current crisis of nationalism, these questions about authentic origin feel especially timely, and relevant to Cleveland, which was once within the top five gateway cities for immigration, and boasting, in 1900, a 33% foreign-born population.

The American Library (2018) by Yinka Shonibare at the Cleveland Public Library, multiple views.

These ideas coalesced for me aboard the William G. Mather, a decommissioned steamship and outpost exhibit docked at the Great Lakes Science Center. Much of the regular cargo hold main display has been cleared to accommodate a rolling screening of the documentary film, Lottery of the Sea (2006), by Allan Sekula, a frankly ponderous, 179-minute odyssey that tackles some of Sekula’s perennial themes: labor, global capitalism, and the sea. Though sitting in a muggy cargo hold on a long, hot press day and attempting to train one’s attention on a meditative and slow-moving examination of the international maritime industry in no way compares to the labor of, say, working on an industrial fishing craft, there is some sense of long and sustained effort that forms a kind of sympathy between the abstract and far-away reality being presented to the viewer, and the immediate surroundings. Afforded an opportunity to speak with artistic director Michelle Grabner directly, I raised this notion of her obviously intentional intersection of external input and locality.

A view of Cleveland from the deck of the steamship William G. Mathers.

“When you think about Sekula, or Vanderhyden at the Federal Reserve, or you go to the library and see Yinka Shonibare, what we’re seeing are artists who are not afraid to take on huge, big themes, that always risk falling into a cliché,” Grabner told Hyperallergic. “The idea of ‘the sea’ is a huge subject, right? Vanderhyden takes on the anxiety around money — that’s a big thing. Yinka Shonibare with immigration — and there’s many more. … I think that works perfectly with the suggestion that there is a kind of intersection that happens, and that is, if you’re going to slice through Cleveland, do it with something that it’s hard not to have a relationship with. Something that’s hard to neglect. We understand we are sitting on water, we deal with money, we deal with immigration on a daily basis. So those two things together will hopefully be what gives this exhibition its impact. That reinforcement might feel flat-footed or obvious, but I think it elevates and reinforces the subjects in a profound way.”

FRONT’s success in this aim notwithstanding, there are a few notable blind spots to its efforts — most strikingly, an overall lack of acknowledgement and elevation of the immediate and regional art community. Using Cleveland as a staging ground for out-of-town artists rings alarmingly close to the kind of ‘blank canvas’ mentality that is all too familiar to long-suffering denizens of Rust Belt cities experiencing redevelopment efforts driven by wealthy benefactors concerned with generating outside interest rather than addressing longstanding, often racialized, systemic inequities.

Detail view of the Martine Syms installation at MoCA.

Certainly, not every sited festival needs to feature local artists, and FRONT is in its first iteration of a Herculean undertaking, but among all the many exercises and exhibitions, only a small handful seem to consider that the people of Cleveland, and artists of the Midwest, have their own set of concerns and a way of presenting them that offers crucial perspective, much-needed awareness, and an opportunity for acknowledgement and healing. No doubt every festival has its shared of green-eyed monsters, but it’s difficult to avoid a sense that those artists who feel marginalized or wallpapered over by FRONT have a point. More or less every regional artist was shoehorned into a group show at the Cleveland Institute of Art, which felt less polished and less considered than many of the other sites—not to mention a bit perilously crowded, with 21 artists in a single venue, culled from a 2017 Great Lakes studio tour undertaken by Grabner.

Though it might be framed as a generous act on the part of Grabner and FRONT to visit the studios of 55 regional artists, this nonetheless feels like an awfully small number in the context of all the artists working in the surrounding Midwest region, which includes Ohio, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, upstate New York, Illinois, and Toronto, Ontario. While it might rightly be argued that truly great artists can shine through, regardless of context or support, it is equally true that many of today’s industry darlings achieved their status largely through being backed by incredible wealth and investment. It feels as though, with the amount of resources obviously brought to bear in Cleveland on FRONT’s behalf, that a greater portion might have been diverted toward helping to polish some of the city and the region’s diamonds in the rough.

Michael Rakowitz talks to press in the collection space for safety orange objects at SPACES.

One of the only venues that made an exhaustive effort to acknowledge the people and the artists of Cleveland was, fittingly, the experimental and community-oriented SPACES, which houses the efforts of artist Michael Rakowitz. The Chicago-base Rakowitz has a longstanding practice that includes regular, direct engagement with people and places, which he expresses in multiple ways in his work for FRONT. Notably, Rakowitz turned over roughly half the gallery space to Cleveland-based artists, reserving only the back room for his own work, “A Color Removed” (2015–ongoing). Both galleries address the police shooting of 12-year-old Cleveland resident Tamir Rice on November 22, 2014. The incident, caught on security footage, rattled the entire country, but was felt especially keenly in Rice’s hometown. Rakowitz installed kiosks to collect any and all items in Cleveland that are “safety orange” — in reference to the so-called justification for the offending officers’ acquittal, which was that Rice was playing with a gun unidentifiable as a toy because the safety orange cap had been removed.

In his campaign to remove all items of this color from Cleveland writ large, and progressively amass and install them in the back room at SPACES, Rakowitz hopes to raise the question of who “deserves to be safe.” The installation continues to attract attention to a personal loss and national issue that remains vitally relevant to the people of Cleveland — particularly in neighborhoods like Glenville, site of a five-day riot exactly 50 years ago this week, into which new development is insinuating itself, under the guise of FRONT and other art-driven concerns.

Detail view of “Civil War” by Josh Kline at MoCA.

Surely, no one festival can do everything, and FRONT has made a bold inaugural effort to establish itself as a contender among the many new art destinations springing up all over the Midwest. There is much to be gained from visiting FRONT, not least of which is an opportunity to explore Cleveland, a city rife with outstanding historical architecture, amazing heartland food culture, and absolutely warm-hearted citizenry. One sees nothing but opportunity to create enhanced resonance and connection, not only to the “canvas” of Cleveland, but also to the people and artists who constitute its weave.

The inaugural FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art continues through September 30 at venues across Cleveland, Akron, and Oberlin, Ohio.