Prodger received her prize from author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Tate director Maria Balshaw Photograph: Peter Nicholls/Reuters

Alex Farquharson, director of Tate Britain, who chaired the judging panel, said Prodger’s work represented the “most profound use of a device as prosaic as the iPhone camera that we’ve seen in art to date”.

Prodger, 44, won for her solo exhibition at the Bergen Kunsthall in Norway, which featured two film works, Bridgit and Stoneymollan Trail. The 32-minute film Bridgit has been on display at Tate Britain as part of its Turner prize exhibition.

The film is difficult to explain. There is lots going on, a lot of it apparently randomly. It explores class, gender, sexuality and neolithic goddesses.

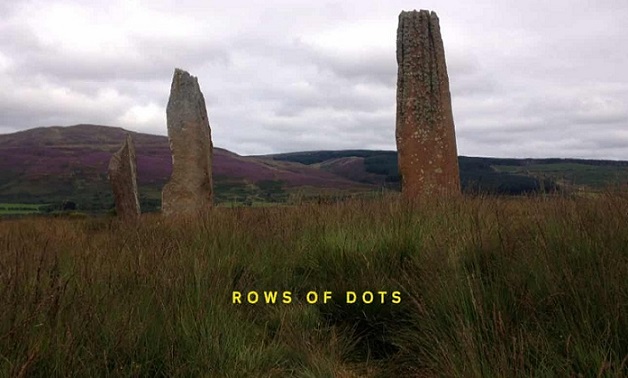

Prodger filmed the work over the course of a year and included footage of her at home and on her travels. Her narration includes snatches of autobiography – coming out in Aberdeenshire in the early 90s, people being unable to tell whether she is a boy or girl, the assumption that her girlfriend is her daughter. She also quotes from Julian Cope’s The Modern Antiquarian.

The artist has described the piece as being about the fluidity of identity from a queer perspective; an exploration of the intertwining of landscape, body, technology and time.

Farquharson said the jury felt Bridgit was “incredibly impressive in the way that it dealt with lived experience, the formation of a sense of self through disparate references”. He said the work evoked traditions in landscape art and had psychological weight. “It ends up being so unexpectedly expansive. This is not what we expect from video clips shot on iPhones.”

It took the jury more than four hours to reach its decision. “I think the jury was united in a feeling that this work was introducing something new to the filmic medium and how it is used in art,” Farquharson said.

All four nominees – three individuals and a collective – made film work, all of it in some way political. Depending on your perspective, this year’s exhibition was either the most wonderfully captivating in memory or the hardest work. Certainly, it is not a show that should be experienced quickly; the Tate recommends four and a half hours.

It has divided critics. The Observer’s Laura Cumming called it the best in years, “by turns shattering, absorbing, beguiling, highly political, frequently momentous”. Waldemar Januszczak in the Sunday Times wrote: “From beginning to end, this soul-crusher of a show is unusually awful.”

The favourite of many visitors had been Forensic Architecture, a collective that has been described as an “architectural detective agency” investigating state crimes and human rights abuses across the world.

Based at Goldsmiths, University of London, the group consists of architects, film-makers, journalists, archaeologists, scientists, lawyers and software developers. For the Turner prize show, it exhibited the results of its investigations into deaths during a 2017 pre-dawn raid by Israeli police on a Bedouin village in the Negev desert.

The Turner prize, running since 1984, often exasperates and thrills in equal measure and is no stranger to controversy. The closest it came this year was protests against the artist Luke Willis Thompson, a New Zealander of European and Fijian heritage.